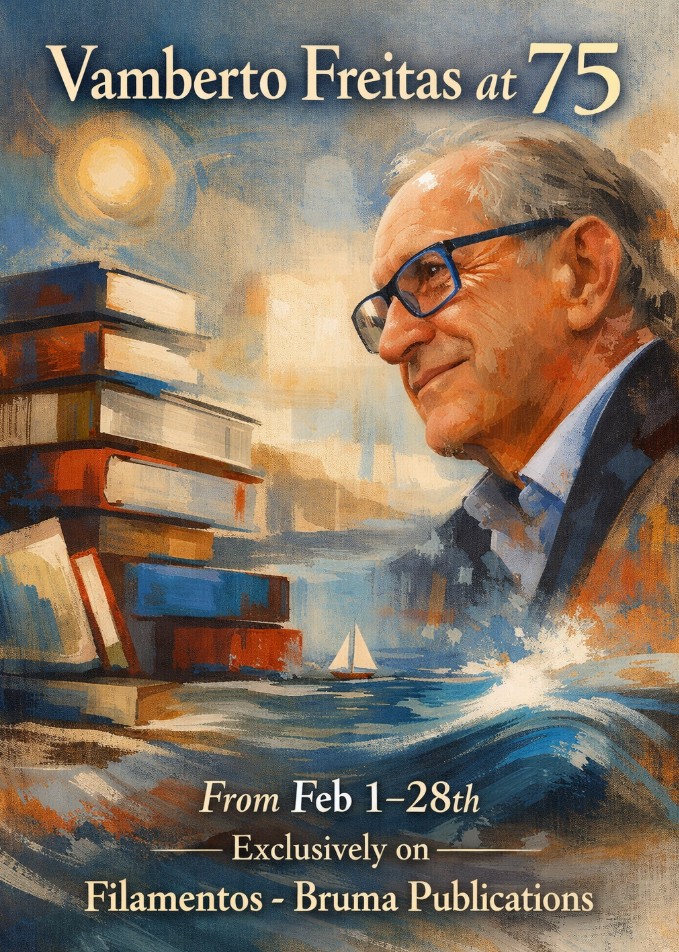

Living Memory of Azorean Wanderings

Vamberto Freitas

Those who have never written through a night of storm do not know what it means to be an islander—

when the horizon disappears, and the damp wind enters the skin, heavy with sea and fog.

—Luís Mesquita de Melo, Navigations and Other Wanderings

Navigações e outras Errância (Navigations and Other Wanderings– in English and used here with that title, not because the book has been translated to English, but for easier connection with the English language reader), by Luís Mesquita de Melo, is a distinguished and magnificent work of prose by an author who, I suspect, is still known only to a limited circle in our country—yet he deserves far more. He deserves a place at the very top of any Portuguese-language bookshelf. His writing clearly emerges from a great tradition within our literature: one that recognizes the Azorean archipelago as an irresistible calling, the islands that inhabit us, a human geography shaped simultaneously by emotional enclosure and by the desire—sometimes necessary, sometimes reckless—for departure into the unknown. For many, departure is survival; for others, it is adventure. The sea is our longest and most seductive road in the search for bread—or the unavoidable fulfillment of fantasies woven by imaginary sirens who lure us toward happiness, or toward another, more distant abyss.

On the back cover of this book, Onésimo Teotónio Almeida writes that few works contain so much sea within them, and that in this respect it can be compared to our Tragic Maritime History, without forgetting two other remarkable writers born of the islands of our Azorean triangle: Dias de Melo (Pico) and Nuno Álvares de Mendonça (São Jorge). Speak, memory, as Vladimir Nabokov once titled one of his inimitable books—first and foremost about the imaginative power of literary transfiguration. We might believe we know a “reality” directly, even the land that cradled our birth and growth, all that shaped our being and instilled in us a worldview—whether of what surrounds us or of what lies beyond the horizon where, as someone once said, the sky kisses the sea.

It is in that space between here and there that the imagination of the finest writers navigates—writers like Luís Mesquita de Melo. What we might call our personal heritage, once rewritten into a sustained literary text of any form, becomes imaginary: fiction overlays what we once considered a structural, above all human geography, transforming it into a broader “truth,” into a durable memory. This is the irreplaceable role of the word turned into art, as it occurs in Navigations and Other Wanderings.

Mesquita de Melo’s authenticity and imagination do not allow us to stop turning page after page. His language—combining stylistic elegance with metaphors of lives reinvented in each section—places us within a singular imaginary that stretches from Pico and Faial, from where he himself would depart into the world, to Brazil (Porto Alegre and the Amazon) and to North America (California): other lands that have always called us both to leave and to return. It is the bold lives of those islands, a daily existence forged in grit and love, that the author seeks to recall, paying homage to terrestrial wanderings and to the struggle against the sea in the famed channel—boats, skiffs, and ships now mythologized in his memory and ours.

Navigations and Other Wanderings contains seven chapters, each titled with the name of a “character,” and another bearing the name of an ill-fated Italian ship, Orione, which meets its end in Horta. These are men and women— islanders or those who arrived here—whose lives crossed the author’s, directly or through intimate ties with those close to him. Once again, we find ourselves suspended between reality and fiction, between resilient memory and the structuring invention of thoughts and emotions attributed to the figures who inhabit these stories.

We read the book as though it were a novel: Azorean nature in its restlessness, the signs of wind, cold, humidity, clouds moving erratically; the parishes and a city as living symbols of the condition of beings inwardly obsessed with the pursuit of their dreams—most often leaping into the sea in pursuit of whales or coastal trade, driven by the desire for adventurous departure already shadowed by the thought of return. Between the physical labor of some, the compulsive navigation and inner life of others—locals and foreigners coexisting in gentle harmony—there emerges a point of encounter, of arrivals and endless departures, long known worldwide as the Sport Café, in the cosmopolitan bay of Horta, over decades and decades.

To write sentences as clean and forceful as those of Luís Mesquita de Melo is the dream of many among us. To recreate characters like these belongs only to novelists who fully command their language, its reinventions, and what might be called the “territory of the heart.” We may roam endlessly across the wider world, but the inexplicable magnetism of the islands never fades. We are, as in these pages, part of all lives surrounded by the omnipotent sea, subject to Neptune’s moods—protected by other gods as often as we are punished. This is how the finest Azorean literature, generation after generation, departs from the island in order to confirm our lived and imagined universality, as all communities must do. Dreams, life, and death walk hand in hand throughout these pages.

Seated—please forgive this long quotation from the chapter “Gilberto”—

at the stone counter facing the channel, Gilberto watches the days pass without pause.

They trail after indecipherable silhouettes of ships, launches, whalers, and sailboats,

destinationless, carried by invisible sailors passing in the distance.

Gilberto’s eyes have grown weaker and no longer reach beyond half the channel.

The island opposite is now only a stain of worn sunlight at every hour of the day.

Gilberto’s hands ache from what he did not do, from the ropes that slipped away, shamelessly.

He no longer has strength.

He too has withered, like the vines that dried beneath the gag of black stone.

No miracle can save them.

No wonder can delay the journey.

Mornings grow colder and the sun takes longer to arrive.

It no longer matters.

There is no other pier waiting for the morning sun.

The launch is merely the memory of another voyage that will one day begin.

Gilberto is bent, like a willow yielding to the wind,

waiting for the most dangerous crossing of all.

I chose this passage almost at random. It expresses an existentialist dimension of these characters, capturing the birth and death of desires, joys, and fears shared by countless others who drift through that real and imagined world—who walk, as we do, through Azorean streets and hills with eyes fixed on the sea, trying to divine God’s weather and the weather of our lives. There is neither a better nor a worse way to stay or to leave the island. We conceal our desires and our moorings. Our silence is a continuous inward cry; our gaze comes from the deepest history, hiding and rebelling in mid-ocean solitude—this sea sometimes hated, far more often loved than we might care to admit.

Navigations and Other Wanderings reflects all this with the brilliance of our waters on luminous days, and with their defiance on days of leaden darkness. Salvation lies temporarily elsewhere; returning home is a mandate that may be disobeyed or thwarted by fate. Yet the memory of origins is the sweet and at the same time lacerating fortune that was—and is—given to us to live.

Navigations and Other Wanderings is Luís Mesquita de Melo’s second book. The Humidity of Days—which I have not yet read, but now feel compelled to—was published by Macau’s Capítulo Oriental press. Born in Horta in 1964 and trained in Law at the University of Lisbon, his wanderings soon turned toward the far side of the world, through corporate representation work connected to the casino industry. Great writing emerges from all quadrants of our multiple existences. Lusophone literature is one of endless pilgrimages; its greatness seems always magnified in relation to the smallness of our lands. It embraces every path without explanation, so that what is distant and strange ceases to be so.

Luís Mesquita de Melo, Navegação e Outras Errâncias.

Lajes do Pico: Companhia das Ilhas, 2021.

Originally published in BorderCrossings, Açoriano Oriental, September 16, 2022.