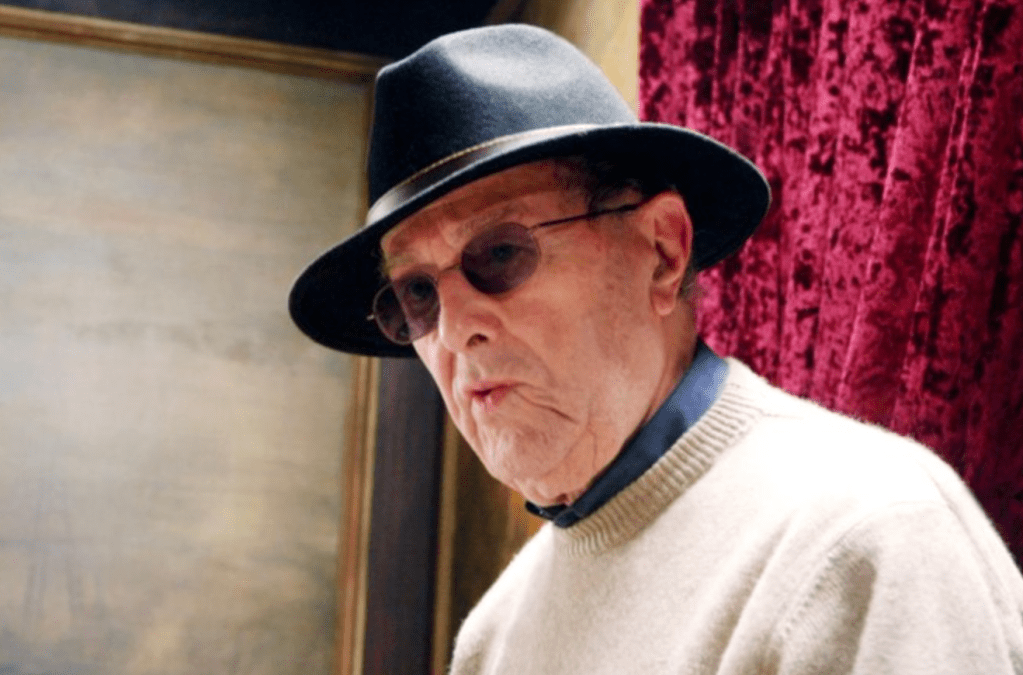

Manoel de Oliveira was born on December 11, 1908, at a moment when cinema itself was barely learning how to breathe. By the time he died in 2015, the art he had entered as a silent, flickering experiment had become digital, global, and omnipresent. Between those two moments stretches one of the most extraordinary artistic lives in the history of cinema—an 84-year filmmaking career that is less a résumé than a meditation on time itself.

Oliveira made his directorial debut in 1931 with Douro, Faina Fluvial, a documentary poem carved from movement, labor, and light along the Douro River. Already present in this early work is what would define his cinema: a contemplative gaze, an ethical seriousness, and a refusal to rush meaning into form. Over the decades, his filmography grew to include more than 50 works, 32 of them feature-length films, each marked by a rigorous attention to language, gesture, and duration. Oliveira never chased novelty; instead, he allowed cinema to age with him, to mature, deepen, and slow.

Uniquely, Manoel de Oliveira traversed every major technological transformation of the medium. He began in silent cinema and continued into sound, moved from black and white to color, from nitrate film to digital formats. Yet his work never surrendered to technology; rather, technology submitted to his vision. For Oliveira, cinema was not spectacle but inquiry—into faith, desire, power, literature, history, and the moral weight of human actions. His films often unfold like philosophical dialogues, borrowing from classical theater, literary traditions, and Catholic metaphysics, while remaining profoundly modern in their austerity.

International recognition came steadily, if sometimes belatedly. The world’s major film festivals—Cannes, Venice, Berlin—honored him not merely as a master but as a singular conscience within cinema. He became known, almost mythically, as the “oldest active filmmaker,” continuing to direct films well into his centenary, completing works at 100, 103, and finally 106 years of age. His last film, Um Século de Energia (2015), released the year of his death, reads like a quiet farewell—not only to cinema, but to the century he had so attentively observed.

What makes Manoel de Oliveira enduring is not simply longevity, but coherence. Across decades marked by political upheaval, dictatorship, revolution, and democracy in Portugal, his cinema remained steadfastly intellectual and morally demanding. He resisted easy narratives and commercial formulas, insisting instead on cinema as a space for thought. His films ask the viewer not to consume, but to contemplate—to sit with silence, to listen to words, to accept slowness as a form of truth.

On this day, December 11, we do not simply commemorate the birth of a filmmaker. We remember a man who treated cinema as a lifelong ethical practice, a discipline of attention, and a dialogue with mortality. Manoel de Oliveira did not outlive cinema; he accompanied it, patiently, across a century. In doing so, he reminded us that true art does not race against time—it walks beside it.