Interview by Telmo Nunes with Vasco Pereira da Costa in Diário dos Açores.

Reading Vasco Pereira da Costa is always a challenging and very enriching experience! The delight of his writing is almost sensory; there is a mixture of erudition, lyricism, and, above all, labor and literary dedication. A man of many arts and crafts, we find in Culture the spark that drives this proud Azorean, from Angra, who has surrendered to the charms of Coimbra.

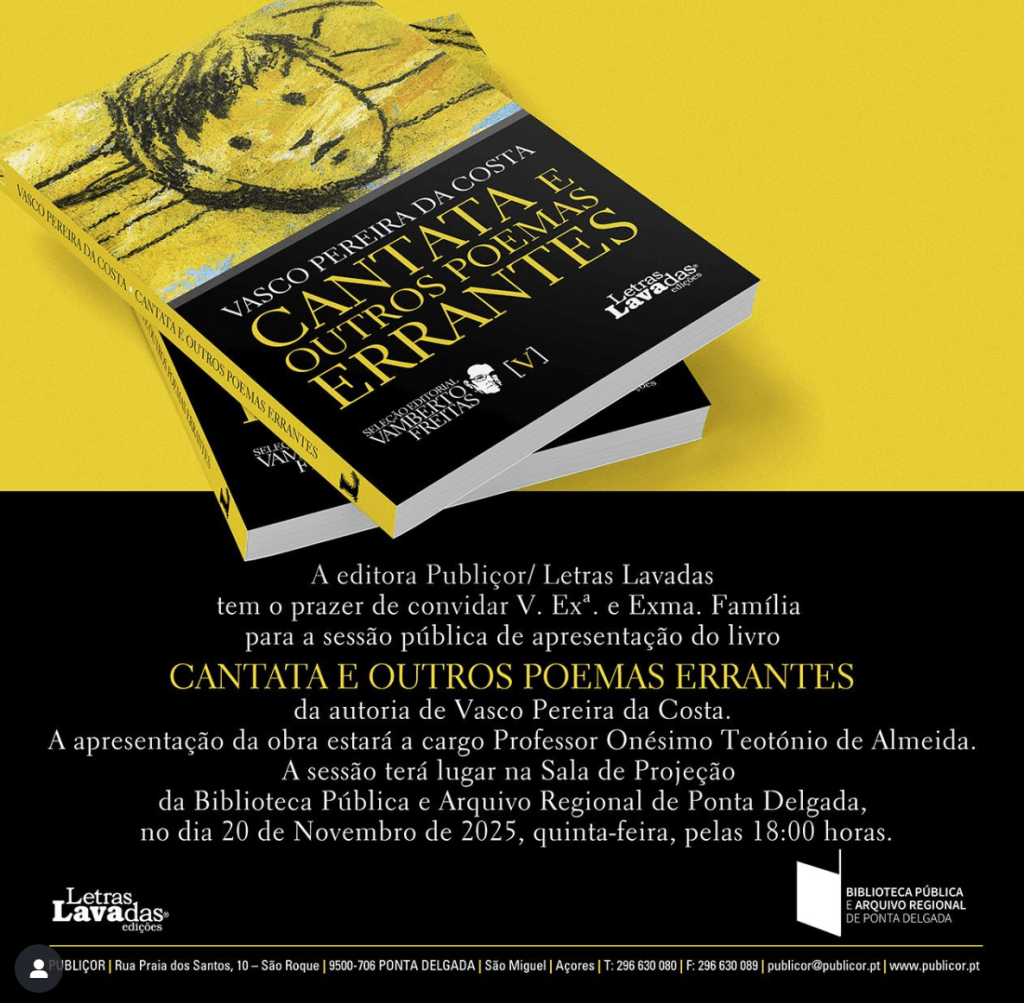

Vasco Pereira da Costa launches this month, November 20th – at Ponta Delgada Public Library and Regional Archive – another book, Cantata e Outros Poemas Errantes (ed. Letras Lavadas), which brings together his latest poems.

Can you define your own poetry? If so, what would you say about it? The creation of a poem requires verbal material for a craft similar to that of a luthier who selects the best woods to build, for example, a violin—spruce, willow, ebony… It is up to the poet to choose the appropriate words in morphosyntax so that the poetic emerges well and with the right sound. The very definition of lyricism points to ancestral musicality. The problem for those who write poetry is that everything has already been written about human life: the Greeks established this simultaneously tragic and comic canon to express the passing of any human being. Therefore, the essence of life—sadness and joy, oppression and freedom, desires and frustrations—must be inscribed in the poem in a different way, reviving the right word.

If Vasco had to choose today the poet and poem of his life, which would they be?

Hui!… it’s difficult: it would have to be from Pindar to Ruy Belo. It would be a chaotic lyrical symphony.

I am not a man of a single book or a single time. By training, I have recorded readings of Romance literature from all periods, as well as translations of writers from all latitudes, following the principle that human nature has no boundaries drawn with a ruler and set square. In fact, human vileness and joy are the same as ever, and the stupidity of governments has always been redeemed by the power of liberating writing.

In literary production, it is very common to talk about “inspiration”; however, inspiration is only the spark that triggers everything else, with study and persistence representing the most significant part in the execution of a poem. Do you agree with this statement? Where does your inspiration come from?

I don’t remember who said it (but it is exemplary) that inspiration is the result of a long-matured thought; the words of Drummond de Andrade alert me: what you think and what you feel is not yet poetry; I recall Torga’s warning to Alegre – the first verse is offered, the others you have to conquer… That is why poems are rarely immaculate: many amendments and much torn paper until a satisfactory form and content are found. To this end, a workshop of inventive and recreative refinement that marks contemporaneity is necessary.

All poets, and writers in general, develop a personal relationship with writing. The text, specifically, poems are not born without a writing process. What is yours?

I always write on draft paper. I write by hand, therefore. At the first verse, the poem chooses its own course, which will not correspond exactly to what I had imagined: it demands the word it wants, the sound that suits it, the measure that fits it. And I have to obey its whims. Then it has to be polished, washed and dried: neither too many words nor too few – only those that are necessary. From the draft, annotated and amended, it is sent to Word and waits for frequent visits that may further improve it. And I never find it perfect… But it may happen that it goes in search of a reader who will accept it. Many poems, however, hibernate indefinitely.

Is poetry still the place where everything can be said? What can readers expect in this Cantata and Other Wandering Poems?

I can only hope that there will be a reader who will take ownership of a poem and welcome it as their own. I don’t dare to think about the future, but I would appreciate it if my writings could be read a hundred years from now. Mere and sad presumption…

One of the epigraphs that opens this Cantata and Other Wandering Poems is “What is most valuable in poetry is the unspeakable, and that is why the most important thing is what happens between the lines.” The quote is by Pierre Reverdy, taken from the work Le Livre de bonbord. Does this mean that the reader, when reading your new book, will have to be constantly in the process of inference?

All literary text is based on metaphor and/or metonymy. It is, therefore, essentially connotative, that is, it allows for a wide variety of readings. Lyrical text, which is synthetic and laborious, uses appropriate semantics and significant phonetic aspects to challenge the reader with its structure. It is necessary to be aware that lyricism carries a ballast of music and that almost all literature was initially oral, resorting to rhyme or short and long vowels or a meter that favored the memory and transmission of texts.

In the poem that opens this book, Vasco says: God is an impure particle of dark matter / wandering in the impudent energy / that tears apart the galaxies of poetry. How is God present in your poetic work? Has there been any evolution in His presence over the years?

Life has given me the opportunity to travel the world, and everywhere I have encountered religious manifestations—all different, but all based on the assumption of a deity or deities. In all of them, there is a need to try to explain life through supernatural, perhaps deterministic, intervention. However, I was not blessed with belief or faith in my Judeo-Christian culture: I am just an animal who was fortunate enough to be endowed, like my peers, with an evolution that shaped me with the development of frontal lobes. I was born this way and, in my animal condition, I am certain that one day I will die. And I cannot predict what will happen after that end.

Your “Christmas Poem” opens with: Nemésio’s shell will never be my home / I am incapable of weaving a cocoon or a marine carapace. How did Vasco manage to resolve this dichotomy of insularity vs. continentality, or does it still cause him some anguish?

There is no dichotomy: there is, rather, an immense territory that we inhabit and to which we belong without border constraints, without temporal barriers, without cultural prejudices: we are all inhabitants of the same planet—a wonderful and fantastic condominium—so often mistreated by the greed and stupidity of the powerful.

Where does Vasco feel he is “coming home”?

Perhaps it is a Camonian ray of light; perhaps it is a legacy of Fernão Mendes, who painted the world; perhaps it is the memory of the photographs of Nova do Achamento, perhaps it is a chapter by Érico Veríssimo or an excerpt from Melville. But, being Iberian, I have always felt at home even in the far corners of the world. I do not deny my birthright in a house on Rua Direita, in Angra, from which I gazed at the inviting sea or scanned the skies for planes crossing the seductive skies of the planet’s discoveries.

Vasco has long expressed himself in both prose and poetry. Does he have a preference for either literary form? If so, why?

Any literary text is poetic—whether in prose or verse. If it is not, it is not literature. The literary character of any text comes from its ability to seduce the reader and remain relevant in any era.

I am sure you follow Azorean literary production, especially poetry. Where is contemporary Azorean poetry heading?

Walking makes the path, sailing chooses the routes. Only chronological time will establish the conditions for survival. The Azorean soil is no different from the steppes, deserts, mangroves, mountains, plains… where various codes of communication can be found. Everywhere, there are creators and receivers of words, different languages. On Azorean soil, this communication is done through the Portuguese language!

Which contemporary Azorean poets do you appreciate? And of those who are part of the history of the Azores, is there anyone you consider a reference?

I would start with Homer… and this interview would take up several pages with the list. Literature does not care about the birthplace of writers. But I will mention a few: Petrarch, Dante, Ungaretti, Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Camões, Bocage, Garrett. Llorca, Machado, Lope de Vega, Manuel Maria, Verdaguer, Tzara, Torga, Alegre, Neruda, Guimarães Rosa, Lispector… the list is endless.

What can your readers expect in the future? Do you have any projects in mind?

I only have one project, which I will share with a quote from António Ferreira’s Letter to Pero Vaz de Caminha:

May it flourish, sing, be heard, and live

The Portuguese language, and wherever

Translated by Diniz Borges