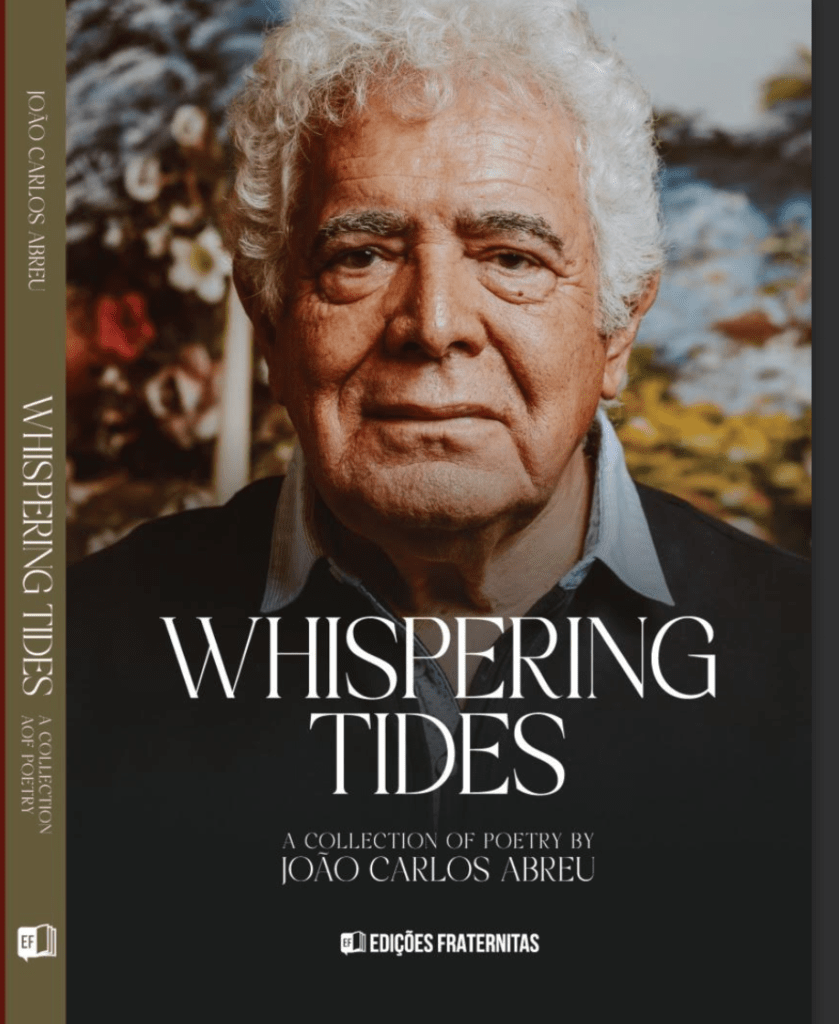

João Carlos Abreu’s Whispering Tides, translated into English by Diniz Borges, is far more than a poetry collection—it is a testament to a life lived in dialogue with the sea, the Island of Madeira, and the human condition. With lyrical force, introspective honesty, and unwavering love for his land and people, Abreu charts an intimate and universal map of identity, longing, and liberation. Through these poems, the reader is drawn into the rhythm of tides that whisper not only of home but of exile, not only of solitude but of belonging.

From the opening pages, the preface by Vítor F. Sousa offers a resonant insight into the soul of the work, proclaiming Abreu as an “artisan of a long poetic journey,” whose vision never confines itself to the island’s perimeter. Rather, his is a poetry that soars: “The movement is always upwards, made up of the ecstasy and longing with which JCA loves life, people, the Island, the world”. That contradiction—of rootedness and flight—defines much of Whispering Tides.

The Island as Compass and Mirror

Madeira, the poet’s island, is ever-present—not only as a geographical referent but as a metaphor and mirror. It is a place of both imprisonment and transcendence, as in the poem “Autonomy,” where the speaker kneels “on the sweaty terraces / of your gigantic people / now more dignified,” their prayers a mosaic of volcanic rock and liberation. Here, the poet does not romanticize isolation; instead, they honor the dignity it brings.

In “Island,” he writes with paradoxical clarity:

“I am Island / Living in a / blue Atlantic that / transmits the angry sweetness of the sea.”

This duality—the tenderness and the tempest—is the condition of islandhood. The island does not limit him; it compels him toward universality:

“I’ve never let myself / close in on the island… / I understood the universal language of peoples”.

Even when physically distant, as in “New York, New York,” the poet is tethered to the island. The island “bursts” within him, as he writes in “My Island,” with the force of volcanoes and the passion of dreams. It becomes a spiritual compass through which he understands other worlds and returns to his own center.

The Sea as Metaphor for Freedom and Diaspora

The sea in Whispering Tides is more than a backdrop; it is a character, a gatekeeper, a confessor. In the poem “Autumn,” Abreu declares:

“This sea / is the goal of my madness. / This sea / is the door to my universality.”

The sea is the route of migration and exile, but it is also the rhythm of freedom. The Madeiran diaspora—especially in the Americas—is evoked in poems like “Meeting,” where “ships come to the sea / loaded with friendship / thousand thread fabrics / and tears of longing.” The sea carries the ache of separation and the possibility of return.

In “Reincarnation,” Abreu speaks to a diasporic metaphysics, suggesting return in forms both tangible and symbolic:

“I’ll be back / in the smoke from the chimney / of a ship, / on the wings of a seagull…”

This cyclical vision affirms that the sea does not only divide—it also binds. It is the fluid geography of memory and kinship. In “Salty Taste,” the tears of mothers, the lips of fishermen, and the eyes of the excluded bear the salt of longing. The sea contains all of it.

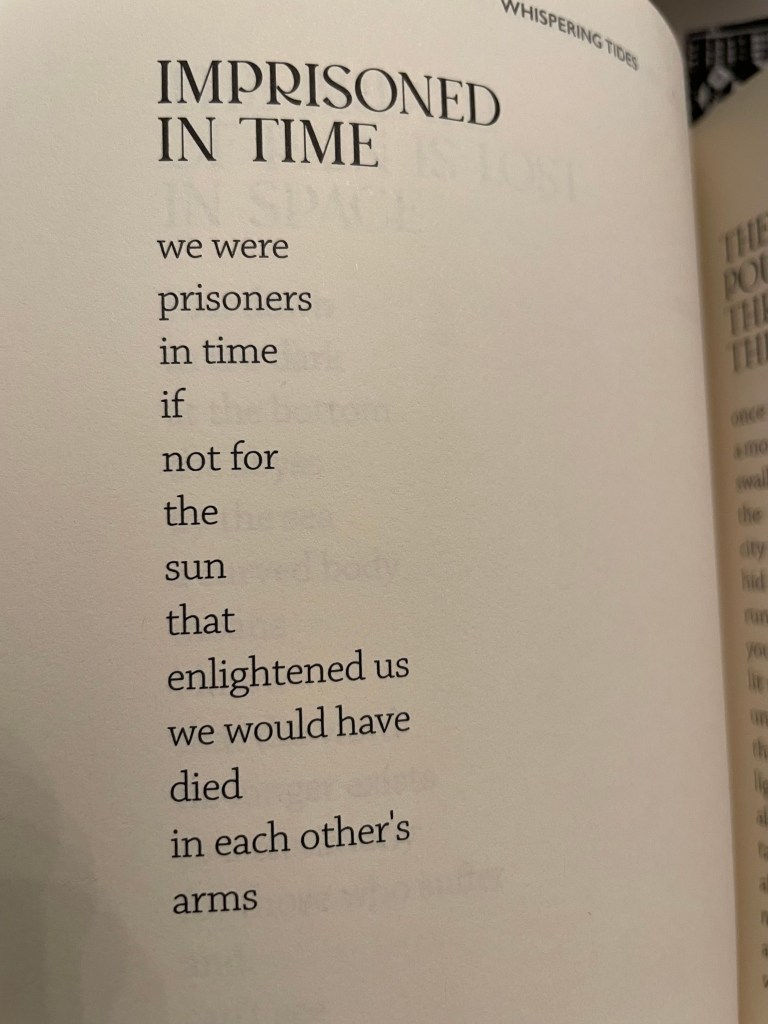

Solitude, Equality, and the Freedom to Love

Many poems in Whispering Tides inhabit solitude not as a void but as a necessary inward voyage. “Losing Myself” offers a poignant paradox:

“I lost myself / in the great crowds of the world / I found myself / in the narrow alleys of my Island.”

Abreu’s solitude is not despairing but generative—it allows for clarity, empathy, and ultimately, a call for freedom. In “Freedom to Love,” he writes:

“From the rocks / I made the balance / of my life / in the abysses / I wrote / the stories / of my passions… / in the freedom to love.”

His freedom is deeply personal, yet it has a profound impact on the political landscape. Equality is not just demanded; it is constructed in the gestures of love, resilience, and poetic truth. In “The New Man,” the call is utopian and urgent:

“Make yourself a prayer / of universal love / illuminate the steps / of the children from your country.”

These lines are not metaphors alone; they are directive. The poet, once a government minister and public figure, understands the weight of words. In this collection, he renounces dogma and embraces the radical freedom of love untethered to gender, nation, or expectation. In the prayer-like “Why, Lord, Why?,” he asks:

“Is it a sin / to love / without religions / to love / genderless / without / concepts / without / rules…?”

The poet’s insistence on love as the supreme freedom echoes through every tide.

Translating the Soul of Madeira

As the translator of this work, I found myself in deep communion not only with João Carlos Abreu’s poetry but with the diasporic echoes it carries. The Madeiran diaspora, particularly in North America, is often overlooked in Lusophone cultural discourse. With Whispering Tides, I saw an opportunity to bring a vital voice to English-speaking descendants of Madeira—those whose grandparents spoke of Funchal or Câmara de Lobos, whose parents danced to Madeiran folklore, but who themselves perhaps never learned Portuguese.

Translation in this context is more than linguistic—it is cultural preservation and revival. It is an offering. Abreu’s poems, filled with longing and flame, become touchstones for those seeking identity. For the Madeiran diaspora, especially its younger generations, this book can serve as a return voyage to an island they may never have physically known but that lives within them.

Abreu writes:

“Sometimes / only sometimes / I think / that the Island / lives / in / me / and / not me / that / lives / in it.”

That is the immigrant and diasporic condition exactly. That line alone justified the labor of translation.

Conclusion: A Map Drawn in Salt and Light

Whispering Tides is a cartography of the interior and the exterior—a map drawn in salt and light. It speaks of the Island as both origin and myth, the sea as both barrier and bridge, and love as the last refuge of truth. João Carlos Abreu’s voice is not confined to Madeira; it echoes across the Atlantic and touches every person who has ever left home in search of it.

In the closing pages of the book, Abreu declares:

“Let me hear it / Beethoven’s sonatas 1 and 14. / I leave you with just one piece of advice: / LOVE WITH LOVE.”

This is not merely farewell—it is a poetic benediction. It reminds us that even as the poet journeys “where vertigo guides me,” what endures is love: for the island, for the sea, for humankind.

May Whispering Tides continue to whisper across oceans, reminding us that the Island is not only a place, but a way of feeling the world—with tenderness, resilience, and a passion that transcends borders.

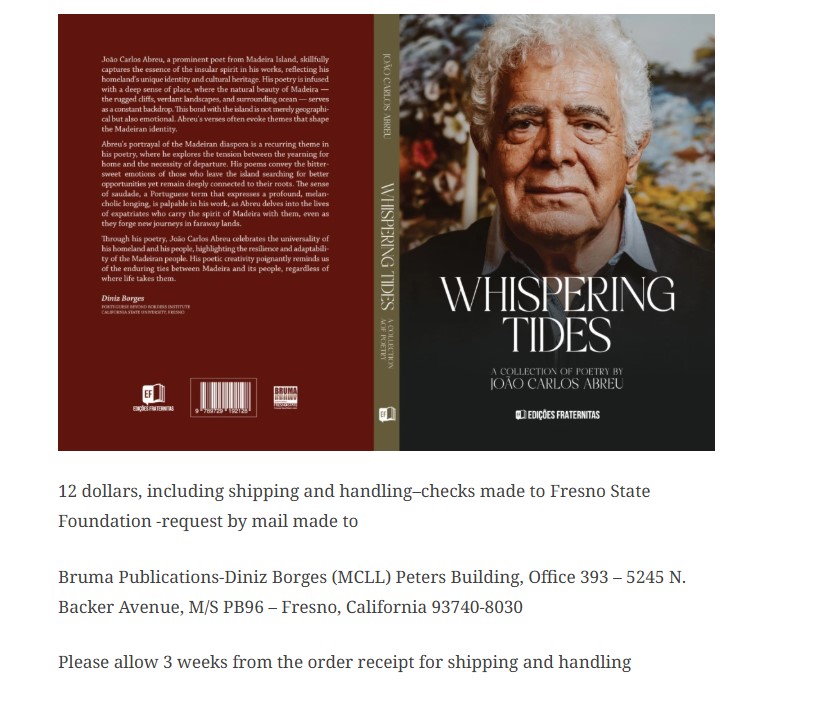

The book is available by mail through Bruma Publications at PBBI at Fresno State.