In Calligraphy of the Birds, Ângela de Almeida composes a lyrical symphony that moves delicately between memory and silence, rupture and return, and rootedness and flight. Through a poetic voice that is simultaneously intimate and philosophical, she crafts a vision of existence marked by tenderness and loss, by the struggle for meaning and the persistent search for belonging. The book that I had the pleasure of editing stands as a luminous offering to readers of Portuguese poetry and Azorean-descended audiences across North America who may now access these verses in their inherited or chosen tongue. The poetic translation ensures that Almeida’s voice reaches across oceans geographically, emotionally, and generationally.

Ângela de Almeida’s poetic world is constructed around a profound sense of fragility and resistance, rendered in both elemental and ephemeral imagery. Birds, rivers, skin, wheat, stones, and hands become the materials through which human experience is explored and inscribed. The titular “calligraphy” of the birds is not simply ornamental — it becomes a metaphor for writing itself, for memory in motion, for fleeting presences attempting to leave a trace. The birds are fragile yet enduring, always in flight, always escaping. They return and vanish. They mirror the condition of exile, diaspora, and poetic creation.

Thematically, Calligraphy of the Birds orbits around several axes: identity and displacement, love and loss, memory and the passing of time, political trauma, and spiritual contemplation. It is a book of cycles — of “delirium,” “Ithaca,” and “hours” — each echoing classical and existential longings. For instance, the “Cycle of Hours” evokes the repetitive nature of time and the inevitable erosion it brings while also casting light on the everyday beauty that passes unnoticed. The “Cycle of Ithaca” invokes the mythic weight of return — Ithaca as a metaphor for home, the unreachable center of self, and a utopia of rest after the violence of wandering.

In these poems, Ângela de Almeida often invokes the body — particularly the skin and the hands — as an inscription site. “The calligraphy of the birds quiets the rifts of the skin,” she writes, offering both consolation and a subtle suggestion that the body is a map, a surface where love, war, history, and desire leave their marks. These “rifts” are not merely physical but also psychic, cultural, and intergenerational. The poet invites us to consider how language — especially poetic — can soothe or expose those wounds.

The political undercurrents of the book are never overt but emerge with devastating clarity. In one passage, she writes of “the howl / of the dogs / set to die today / in Myanmar / and Syria,” and contrasts this with “the applause [that] will be the / lone bullet.” Here, Almeida’s poetry becomes a vehicle of ethical witnessing. Without preaching or polemic, she embeds global suffering into her verses, offering a chorus of lament for the voiceless and displaced. Her approach is subtle, elliptical, and compassionate — refusing spectacle, choosing instead the quiet resonance of empathy.

There is also, woven throughout the work, a spiritual yearning, a metaphysical dimension that questions political and existential borders. In a poem dedicated to Ricardo Reis, a heteronym of Fernando Pessoa known for stoic detachment and contemplation, Almeida writes: “Let us simply embrace each other / and continue to look at the bluish / satiny cloak / as if time were this moment / so smooth and astonished.” In her work, time is both wound and wonder — an open field where memory is cultivated and lost.

Ângela de Almeida’s engagement with Azorean identity, while never reduced to regionalism, is quietly omnipresent. The landscapes she evokes — the fields, the wisterias, the rain, the stones all carry the pulse of the islands. But more than physical scenery, what pervades her poetry is an Azorean sense of saudade: that uniquely Portuguese longing for what is absent, unreachable, half-remembered. In this way, her poetry speaks deeply about the diasporic condition. For Azorean-Americans and Azorean-Canadians, the poems mirror ancestral emotions — a way to reconnect with roots not through nostalgia but through lived poetic truth.

Translation thus becomes not just a literary task but a cultural mission. As a translator of this extremely important poetry into the English language, I tried to maintain the delicate rhythms and images of the original, making the poems accessible without flattening their emotional complexity. I believe this translation opens a door for second- or third-generation readers of Azorean descent who may not speak Portuguese fluently but feel a deep connection to their heritage. It allows the diaspora to reclaim a voice they may not have realized has always belonged to them.

In a global literary culture that often overlooks Lusophone writers, especially those from the periphery of Portugal — the islands, the margins — translating Almeida’s work into English, from my humble perspective, helps to expand the canon. It asserts that voices from places like the Azores matter and that their visions — though local in reference — are universally resonant. The calligraphy of these birds writes across borders.

The translation also deepens our understanding of feminine experience, as Ângela de Almeida’s voice often moves within the realm of womanhood — not in reductive terms, but in gestures of intimacy, vulnerability, and strength. Her poems speak of motherhood, aging, touch, and the quiet gestures of care and memory that shape a life.

Diniz Borges, translator

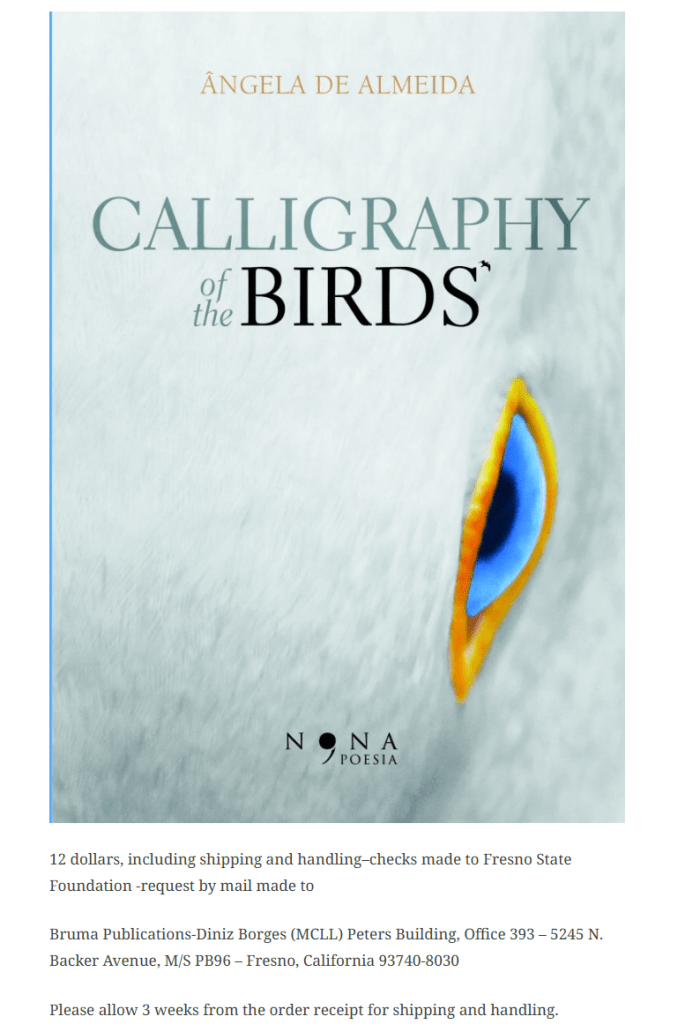

To order the English Edition

To order the Bilingual Portuguese-English Edition

In the Azores, you can order through Letras Lavadas and the Bookstores that work with the publisher or online at https://www.letraslavadas.pt/