Photo from RTP-Açores

Translated by Katharine F. Baker

As a septuagenarian, I wonder with amazement about my generation’s legacy.

– Vasco Pereira da Costa

Vamberto Freitas: Should a reader ask what leads me to hold these conversations with writers from different generations, I reply as simply as possible. They have been having dialogs in person at various literary meetings everywhere for years, but I wanted readers dedicated to our Portuguese-language literature to have a clear idea once again of our intellectual, particularly our literary, evolution, which has naturally always accompanied our history and circumstances that are centuries – not just years or decades – old.

Vasco’s writing represents to me a clear symbol of the years in the leaden era and in freedom. The memory of those times and the journey of a people, of peoples everywhere, as I have written many times, is the dominant theme of all great world literature. Azoreans, both inside and outside the archipelago – as others have already noted long before me – have always led the way in producing one of the great literatures of Portugal and its outer reaches, which is the whole world. These works are translated into various languages, from Japan to some European countries, and are still read throughout the world that speaks and writes in the language of Camões. Someone once wrote regarding these matters that territory has nothing to do with the map. In other words, great literature has always been born in the most hidden places on the planet.

Here then is Vasco Pereira da Costa, whose islands are surrounded by both sea and endless land. His work was recently mentioned in the “Borders Crossings” pages of Açoriano Oriental. Now all that remains is to know what moves and touches this great writer, born in Angra do Heroísmo and residing in Coimbra since he entered the Faculty of Arts at the University of Coimbra at age 18, and would later head the Regional Directorate of Culture in the Azores for nearly eight years.

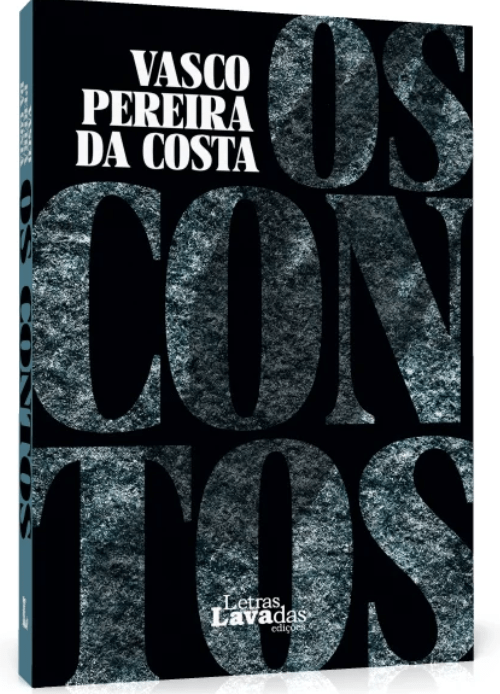

He has just published Os Contos, an anthology of his greatest prose, organized by Telmo R. Nunes.

VF: Your literary work dates from the ‘70s/’80s to the present day. What motivates you for this relentless and enduring writing?

Vasco Pereira da Costa: I have incorporated writing into my life the way a philatelist spends hours gazing at postage stamps. I keep seeing an untold story or verse that demands precise wording. It is not an implacable motivation that does not seek durability, but one that comforts those who have become accustomed to treating literature as a very close relative that can be trusted and has never disappointed, despite great discussions. So writing is a willful act, or as Miguel Torga said, an ontological act.

VF: Which readers do you have in mind when you write poetry and prose?

VPC: I have no idea who will avail themselves of my texts, nor does that matter concern me. I only know I would not accept any editorial imposition – thematic or temporal. Literary creation is based on total and irrefutable freedom of thought. I admire those who manage to earn enough from what they write, although nowadays many literary products are supported by marketing campaigns. Just look at the profusion of writers who concomitantly read television news.

Happily, due to my nature and pride I have escaped the media, because I truly value my privacy and do not need to write for my survival. However, it is a task that requires patient, detailed and persistent work. I think often of Daudet’s short story The Man with the Golden Brain, in which pieces of this precious metal are gradually removed until at last only a few bloody nuggets remain: dictionaries are nothing more than those tiny lymphatic bits into which writers have to breathe new life. They can give words vileness or virtues, vigor or decay, hate or love, peace or war, heroism or cowardice, simplicity or complexity, humanity or beastliness, magnificence or shame, sympathy or repulsion.

That is the great power conferred on the act of writing, which is not always achieved, as of course there is much revising and torn-up paper. And it is always advisable to let a work rest, so that after considerable time has passed you can understand whether its functional and aesthetic qualities still remain intact. Readers have to be respected, so we cannot give them insignificant, tired, haphazard, useless and fearful stupidities or decorative trinkets. Any text – literary text – is always a challenge cast for those who will read it. And the writer will then never again be its owner and master; readers will forever appropriate what they have read, generating their own texts.

I note the following contradiction, however: never has so much been published on paper or digitally, yet reading rates remain very low despite the proliferation of public and school libraries – and, well, because the outlook would be more devastating and disturbing.

Photo–https://www.diariocoimbra.pt/2024/12/09/vasco-pereira-da-costa-vai-lancar-novo-livro/

VF: Humor and, to some extent, satire are constants, particularly in your prose. Is this your way of saying serious things with a laugh, things that worry you and move your literature toward taking into account your communities on the islands and the mainland?

VPC: Irony derives from the unpredictable moment when it intrudes upon writing. After all, we can all be touched by banality and ridicule that lack critical distance; by the affection that touches the human condition; by the concerns that place us in an environment that borders on the tragic and that we want to undo. Any writer simply repeats what has already been written since the time when man, an absolute and strange animal, discovered he had the capacity to express the most diverse feelings.

VF: How do you see or understand this time in our nation today? Does literature still retain a central role in Portuguese thinking and attitude, let us say towards everything and everyone that surrounds us?

VPC: As a septuagenarian, I wonder in amazement about my generation’s legacy. We proclaimed we shall overcome some day; that all you need is love; and that the 25th of April would irrevocably undermine fascism. None of this came to pass. It may be time to put a red carnation in our lapel again and shout once more against all forms of imperialism.

Something went wrong. It occurs to me that in the ‘80s of the past century there was a pie-in-the-sky nefelibata that foreshadowed a society of leisure: thanks to emerging technologies, people would retire earlier and there would be a need to fill their quality of life with cultural leisure.

To this end, community gardening equipment was needed, training of auxiliary technicians for the performing arts, actors, artists, agents… Well, none of it happened: the retirement age rose, the economy contracted, poverty increased, levels of social inequality became more pronounced. And now populism is making a return: Le Pen, Bolsonaro, Trump, Ventura’s Chega party and many other “saviors” who present us with a scenario very close to that in the time of Salazar, Franco, Mussolini and Hitler. The glorious era of humanist, fraternal and egalitarian European peace is fading. Present times portend fearsome war and lack of control in a world at the mercy of financial greed that has no face or fixed address. And this world’s political class has been assaulted by mediocre, illiterate people. I do fear for my children and grandchildren, in fact for all the children and grandchildren perpetuating life on our planet.

What next, Vamberto?

Vamberto Freitas is a literary critic for the “Borders Crossings” page of Açoriano Oriental. The transcript of this interview also appeared in Filamentos on 14 Dec. 2024, at: https://filamentosarteseletras.art/2024/12/14/vasco-pereira-da-costa-quem-escreve-como-escreve-e-para-quem-entrevista-de-vamberto-freitas

Katharine F. Baker’s many translations include (with Diniz Borges) the bilingual edition of Vasco Pereira da Costa’s book My Californian Friends: Poetry (2009).

Pictured in California (2009): Translator Katharine F. Baker, Dr. Eduardo Mayone Dias, and writer Vasco Pereira da Costa.