Azoreanness, or a Chronicle of Longing

By Vamberto Freitas

“Foreigner here as everywhere… A ghost wandering through halls of memory.”

— Fernando Pessoa (Álvaro de Campos, “Lisbon Revisited”)

When I am asked to write about the Azores — about what we call Azoreanness — a thousand worlds immediately crowd my thoughts. I have lived on continents as if they were islands, and on islands as if they were vast continents. “No man is an island,” the poet once wrote. But what if the opposite were true? What if we are all islands? We are geography without a map.

To be Azorean has always meant being at once present and absent — from ourselves, from our own. Vitorino Nemésio, who coined the term Açorianidade, confessed that the feeling intensified when he left Terceira as a young man to study in Coimbra. It was the longing for the shell-island, for those who remained behind. On the island, longing is not for distant lands but for our own who now inhabit them. From here, we are always also from there.

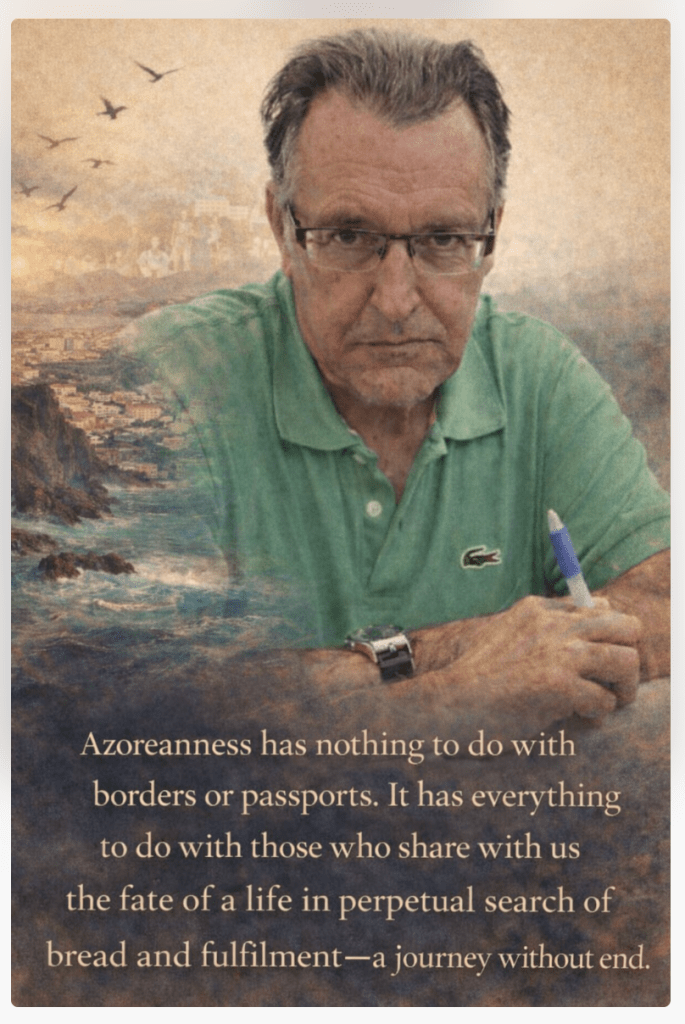

Azoreanness has nothing to do with borders or passports. It has everything to do with those who share with us the fate of a life in perpetual search of bread and fulfillment — the dream as a journey without end. We carry the islands within us, and in return we carry the world back inside.

There was a time when, as a young university student somewhere in Southern California, I would look at my old Portuguese identity card and fail to recognize the person it described — that boy from a place half-lost in the Atlantic. My world had already shifted kingdoms. And yet we are who we are, far beyond any small booklet that claims to legitimize us as citizens. I remember a vague but persistent incompleteness — I had so much, and yet the rest of me was missing. The soul asking to return to its essential terrain.

No one fully chooses who they are. The ancestral cord holds with the strength of roots; it refuses to let us wither, even in foreign soil. When the restlessness became too strong, I would drive three and a half hours at high speed along California’s mythic Highway 99 toward my own people in the San Joaquin Valley. I would arrive, and the island would reassemble itself inside me: the table set, the cadence of my parents’ speech, the smell of the Azores in the kitchen. The certainty of being among those who loved and still love me.

Nemésio strummed his viola in Praia da Vitória or rode horseback in Porto Martins. I, in America’s agricultural heartland, sought out the community halls where fellow countrymen slapped cards down in a game of sueca, swallowed wine, lit cigarettes. When they spotted me, they would simply say, “Look, it’s Vamberto.” That intimate recognition was sustenance enough for months without my people. It reaffirmed not only my belonging to a community of long memory but my very self. Afterward, I could return to other worlds and imagine myself cosmopolitan — whatever that may mean.

Today, even at home in the islands, longing persists. Geography is us. Within its infinite extension reside all those who belong to us and to whom we belong. Or, as Jorge de Sena once wrote — with rare clarity about exile and identity — “I myself am my own homeland.”

Had my age and circumstances been different, I might have sailed again. I returned to Portugal convinced that centuries of disastrous governance and injustice had been buried at the end of the twentieth century by those who, on an April night in 1974, marched from Santarém to Lisbon. The revolution promised a renewed social contract between citizens and the State.

Yet the contract has proven fragile. I do not consider myself entirely free in Portugal. Alongside millions of compatriots, I feel at times reduced to a subject — someone whose security can be dismantled overnight in order to service debts incurred by those who abused power for personal gain. We are instructed to pay “creditors” euphemistically described as “partners” within a supranational European bloc. The language is polite; the consequences are not.

Yes, I am Azorean — and thus historically subject to forces beyond our shores that have long determined the fate of our Atlantic region. To compound insult with injury, we are often portrayed as provincial dependents, accused of disproportionate privilege. I will always be Portuguese. But there are moments when I would prefer to be so from afar, where memory selects dignity and forgets humiliation.

What wounds most is witnessing young people leave once again — in numbers said to surpass those of the dictatorship years. Let us forget statistics. Each era invents its own spirit and rules. The 1974 revolution rekindled hope. It restored people’s value. Yet hope has been eroded. We may not descend into a dictatorship of the old mold, but we inhabit something equally disquieting — a submission to what can only be called international financial authoritarianism. The rhetoric emanating from European authorities in recent years chills the listener. I never experienced such open disdain for a population during my decades in North America — not even in times of profound crisis.

Thus, a chronicle of longing contains multiple geographies — physical and human — and the indelible memory of those who sailed from these islands since their settlement. I once believed that in two or three generations, only the literature of those who continued to write in Portuguese abroad would endure. It appears I was mistaken. Emigration — and all large emigrations are involuntary, despite the romantic myths — is once again underway.

Those who depart are often the bold and the rebellious. Those who remain endure, awaiting another redemptive dawn. Let those who leave tell us of their new experiences in books — of misfortune and triumph. The Americas may yet remain our zones of liberation and renewal. And we who stay will also write — bearing witness to what occurred in the absence of others.

Perhaps they, in truth, are the only universalist Portuguese. In his poem “In Crete with the Minotaur,” Jorge de Sena wrote: “Born in Portugal, of Portuguese parents, / and father of Brazilians in Brazil, / I shall perhaps be North American when there. / I will collect nationalities as shirts are worn and discarded… / I myself am my homeland.”

Literature remains the most durable repository of our collective memory — the invisible counterpart to official history. The language of power, with its numbers and proclamations, fades. What endures are the pages where we record how we lived, how we survived, and how, despite everything, we remained islands — carrying oceans within us.

The first part of this essay was originally published in SATA’s Azorean Spirit magazine (June–August 2013).

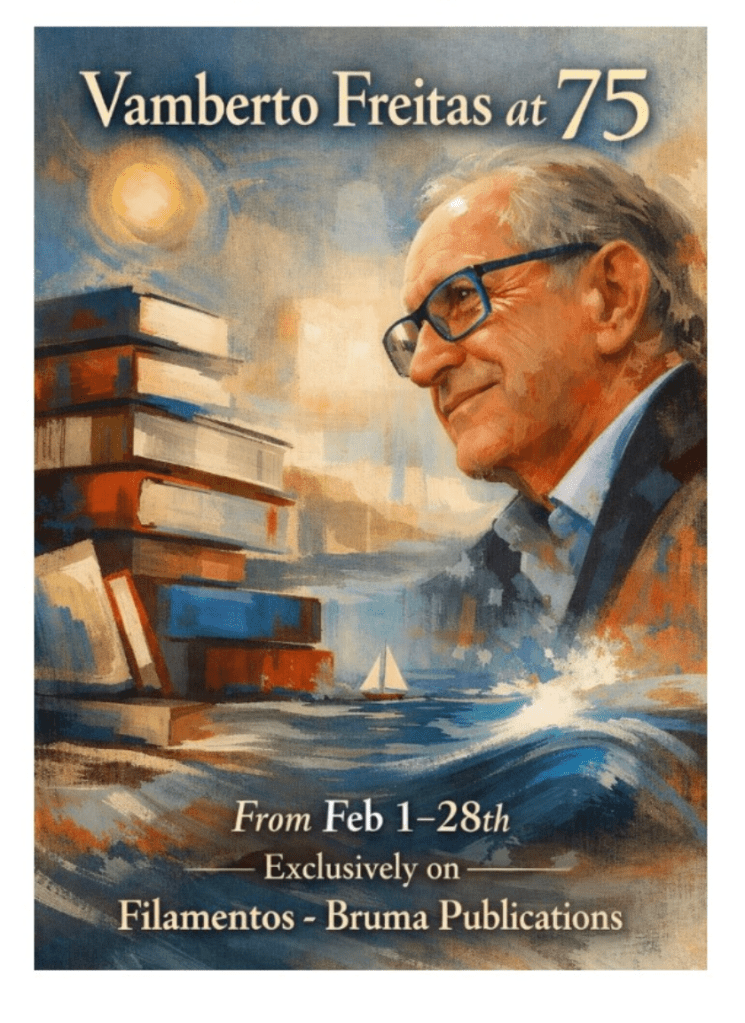

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.