“THROUGH A PORTAGEE GATE”: Lives Told and Reinvented

Vamberto Freitas

He is gone now. His shop is gone. Weld Square is gone. His life has been wiped clean off the board. But I wake in the night and I see his face and I hear his voice.

—“Prologue,” Through a Portagee Gate

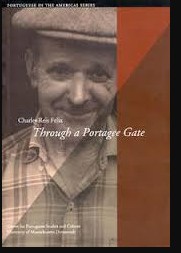

On the cover of Through a Portagee Gate, Charles Reis Felix’s most recent “autobiography,” we find the portrait of a face unmistakably Southern European—instantly recognizable, to a Portuguese reader, as someone who could be one of our own. He might be any man’s father or grandfather. Wearing a traditional cap and a flannel shirt, smiling with an unguarded sincerity, facing the camera without affectation, framed by a background the color of earth, he might have been photographed in Portugal. But he was not. He was photographed in New Bedford, Massachusetts.

He is the author’s father, who emigrated from Setúbal to New Bedford at the beginning of the twentieth century and remained there for the rest of his long and peaceable life. He worked alone as a shoemaker in his own shop—though he preferred, with quiet pride, to call himself a “shoe maker,” dignifying his trade among the competition that surrounded him in his city’s immigrant neighborhoods.

I place the word “autobiography” in quotation marks because this long narrative is that—and more. It is also a biography of the father, and, in a deeper sense, a social history of an entire Portuguese-American community from the 1920s nearly to our own day. It is not the first work of its kind about Portuguese communities on America’s East Coast. But it may be the first to render so fully the life of what was still, in many ways, a “colony”—almost a “ghetto,” though a ghetto in our own manner—one that would gradually transform into a peaceful, orderly, and self-contained community, “surrounded by America on all sides,” as Onésimo T. Almeida might say, pursuing the American dream from the lowest rungs of the social ladder.

New Bedford had by then transitioned from a whaling port to a textile-industrial center, offering livelihood to generations of Portuguese immigrants. They were, in their way, pioneers of a modernity emerging at the margins of society: laboring toward social ascent while serving as indispensable cogs in a harsh, expanding economic machine. The crumbs that fell from the lavish tables of economic and political power were enough to entice those who had left precarious lives behind in Portugal.

Between awareness of their subordinate status and faith in imagined possibilities, these communities took shape—bearing traits distinctively Portuguese and yet shared with French, Irish, Polish, and Jewish immigrants. In this human crucible, Through a Portagee Gate unfolds across nearly five hundred pages, interweaving past and present. We glimpse an America barely visible through narrow fissures in the cultural and political wall separating these Portuguese lives from others—until the arrival of what Felix calls, controversially, the “barbarians”: newcomers who, in his telling, disrupted a once-stable fishing and industrial town with turbulence and crime.

The book is both celebration and elegy: a tribute to a simple life content with its destiny and a lament for what has been lost.

Charles Reis Felix, born in New Bedford to Portuguese parents, left in 1941 to attend the University of Michigan. He fought in Europe during World War II, later recounting that experience in Crossing the Sauer: A Memoir of World War II (2002), a work widely praised for its honesty and literary force. A lifelong writer and former elementary school teacher, Felix now resides in Northern California and, even in retirement, continues to write.

Through a Portagee Gate follows his life chronologically, from childhood awareness in the North End of New Bedford to his father’s death in the 1980s in the same house where the story begins. Yet the narrative opens in the present, as the author explains his purpose: to reconstruct his father’s life, his own, and that of all who shared that time and place.

The word “Portagee” retains its sting, yet Felix reclaims it with redemptive irony. His indignation is sparked by an 1893 anti-immigrant essay in The Yale Review by Francis A. Walker, then president of MIT, warning against the “broken, the corrupt, the abject” flooding American shores. Though Portuguese are not named, Felix knows they are implicated. He reproduces a passage verbatim, then recounts his own experiences of prejudice in California—stereotypes confirmed, ignorance laid bare.

And yet his father’s life stands apart from such indignities. Isolated between shop and home, he refused humiliation. He judged men only through business dealings. America had saved him from poverty; if injustice existed, it was the fault of individuals, not the system. Felix writes not to avenge wrongs done to his father, but to rescue his memory from racism’s erasures—to affirm the dignity with which he lived.

Still, the narrative is not without ambiguity. Felix occasionally reproduces the very ethnic generalizations he resists. “Maybe he really wasn’t Portuguese,” he speculates of his father. “Maybe he was Jewish… I would prefer Jewish to Moorish.” Such passages, unsettling and sincere, reveal the tangled inheritance of identity. George Monteiro, in his preface, notes Felix’s sharp eye for embarrassing detail and ironic casting of character—even among his own people.

The book reads like a novel in fragments, anchored in the shoemaker’s shop and the family kitchen table. There, the father pronounces aphorisms, and the mother—quiet but unforgettable—provides a sardonic counterpoint, questioning, defending, puncturing illusions. Through these domestic scenes, a community’s inner life emerges: its obsessions with financial security, its separateness, its modest dreams.

Felix describes growing up among “Jickies, Frogs, Polocks, and Portagees, with a sprinkling of Jews for flavor. We were all foreigners or the children of foreigners, so we were all equals. There were strange smells coming from every kitchen. Nobody could lord it over anybody else.”

Portugal itself fades in these pages, nearly erased from daily consciousness. Yet in one of the father’s last utterances—“Do you still remember Setúbal, Mary?”—memory flickers. A culture long adrift returns in a single question.

It is ironic that while American writers like John Steinbeck once used the word “Portagee” to demean, Felix and other Luso-descendant authors reclaim it as an act of dignity. That books like Through a Portagee Gate remain largely untranslated and unrecognized in Portugal reveals lingering intellectual blind spots. For a nation fascinated by American culture, the silence surrounding its own diaspora writers is telling.

Yet works like this endure. They stand as literary monuments to the anonymous navigators of the twentieth century—the emigrants who crossed oceans not in caravels but in steerage, seeking survival rather than empire. In telling his father’s story, Charles Reis Felix tells a larger one: of memory against erasure, of dignity against disdain, and of lives that, though lived in the margins, belong fully to the American narrative—and to ours.

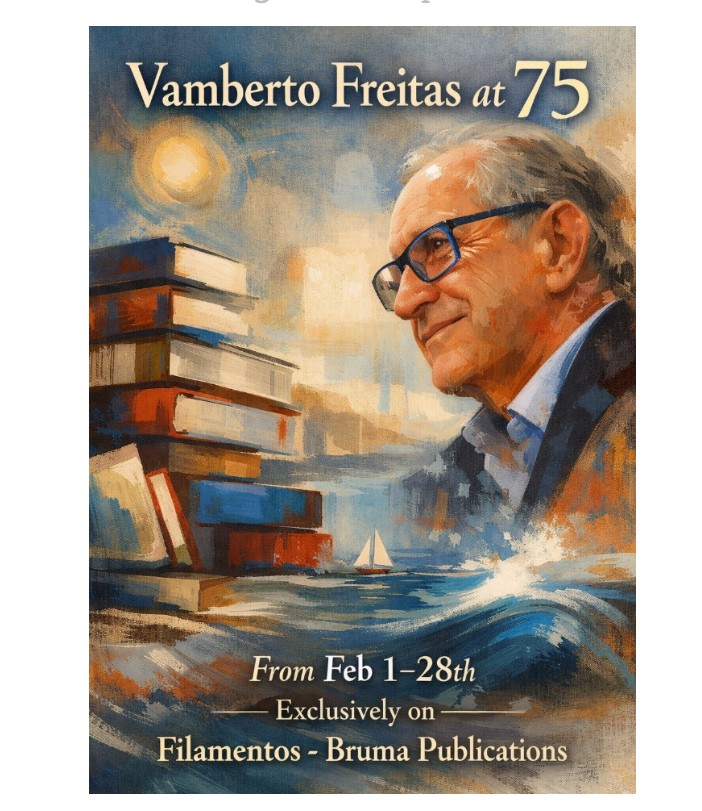

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

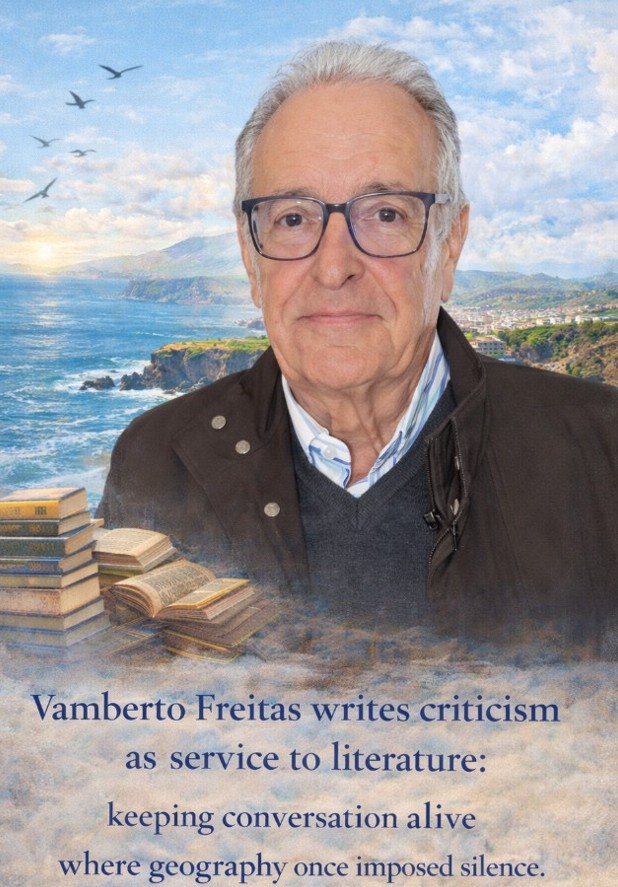

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.