An Azorean Novel That Stands Both Within and Beyond Our Literature

A chorus of laughter and applause breaks out spontaneously. They are happy, at least for now; filming has ended. They anticipate celebration. They embrace. Emotion carries them to tears.

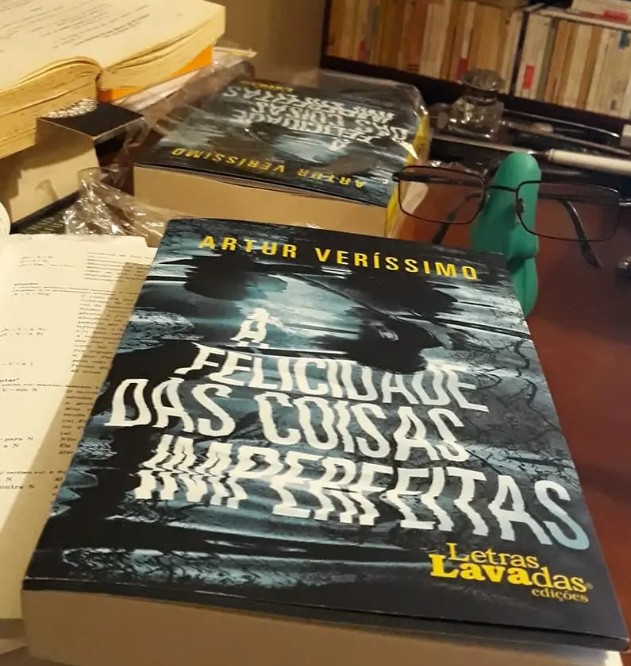

—Artur Veríssimo, The Happiness of Imperfect Things

Vamberto Freitas

Artur Veríssimo, born on Terceira and long resident on São Miguel, has devoted much of his life to public education, publishing in his field with quiet constancy. He is also, unmistakably, one of our major novelists. As someone from my own native island remarked to me recently, he has never sought the spotlight — perhaps never wished for it. Yet there comes a moment in a writer’s life when discretion is no longer enough to shield him from notice.

Awarded for several of his works, Veríssimo has maintained a certain distance — even an aversion — to the rituals of literary promotion. But with The Happiness of Imperfect Things, that reserve can no longer protect him. This novel follows another extraordinary work of his, A Celtic Girl Seated on a Boar, about which I also wrote at the time. Quiet, discreet, without ambition for fame or public recognition, Veríssimo has nonetheless written a book that will inevitably command attention — particularly among readers accustomed to a different kind of fiction emerging from our islands.

I hesitate to call it “Azorean literature.” I prefer instead to say literature that comes out of the Azores — even if it inevitably belongs to the broader body of writing shaped by island life. This is prose rooted in the rhythms of insularity, in departures and returns, in the certainty that however far one travels, the islands remain the gravitational center. Yet there is something radically original in this courageous book. The physical landscape of the Azores is largely absent. It resides not in description but in the interior lives of the characters — some of whom move restlessly between Lisbon, Terceira, São Miguel, Thailand, and America. Geography becomes psychological terrain. The true landscapes are the ones inside the soul.

Formally, too, the novel defies expectation. A journalist-writer named Gabriel Rocha — calm, melancholic — writes his novel even as it is being adapted into a film already in production. He has long been in love with Clara, who leaves for Belgium and other countries for ten years, leaving him suspended in longing. As he constructs the novel, he simultaneously drafts the screenplay. Sometimes the script obeys the novel; sometimes it bends to the vision of the director, José Santa-Marta (whose real-life counterpart one suspects). Scenes unfold on the island, in Lisbon, abroad, and again in the Azores. The result is a layered narrative — novel and film in dialogue, fiction reflecting on its own making.

Throughout, Veríssimo engages in a living conversation with Azorean writers — some named directly in chapter epigraphs (João de Melo, Onésimo Teotónio Almeida, José Martins Garcia), others evoked more obliquely. There are references to foreign authors, to cinema, to classical and popular music. This is a text saturated with intertextuality — playful, erudite, alive.

One of the most intriguing characters is Anuchyd Pòr, a Luso-Thai figure who emerges as a central presence in both the novel and its filmic counterpart. Around him move other secondary yet unsettling figures. At one point, in a gesture that is both ambiguous and mischievous, the narrator alludes to two well-known writers among us, referencing his previous novel in a passage laced with irony and island wit. I laughed aloud reading it. Veríssimo’s humor is constant; so is the pleasure of following his prose.

The Happiness of Imperfect Things — a story foretold, as the novel hints, in seashell divinations — is written in both first and second person by the same narrator. It opens with a quotation from Friedrich Nietzsche and another from Urbano Bettencourt’s What Landscape Will You Erase. From the outset, it signals that it will not dwell on postcard descriptions of island geography. Instead, it plunges into the intimate weather systems of its characters.

Some readers may be startled by its unflinching treatment of sexuality — scenes of desire, of bisexuality, of homosexuality — explored without apology. Veríssimo dismantles the silent codes of small societies, exposing anxieties, pleasures, generational shifts. This is a novel of artistic courage. In communities accustomed to discretion — or to the performance of discretion — such candor can feel radical. But a writer who writes in fear is no writer at all. Art demands risk.

Midway through, the narrator confesses: “I have great difficulty listening to José Santa-Marta. I think of Maria Amália, of my son, of Clara, of Anuchhyd Pòr — and not only them. Of everything except what the director wants. I have no desire to argue with him about the bedroom scene in which Gabriel and Désirée watch The Picture of Dorian Gray on television. I shouldn’t even have proposed it. In truth, we never watched the film together. We never even watched a film in bed… I would rather speak of the photograph before her. It is of the actress who plays Clara in the film. The photographer caught her — wide smile, confident — leaving The Egg. Behind the dark glasses of the character, one senses that José Santa-Marta’s fiction, which has taken her to America, winks at reality. It is Clara returning — at least in the film.”

Elsewhere, the narrator twice italicizes the title Smiling Within the Night, Adelaide Freitas’s novel — a gesture that functions as foreshadowing. Clara, Gabriel’s great love, eventually returns to the island. Friends notice something disquieting in her distant gaze, her broken speech, her drifting attention. She carries a degenerative illness. Fiction edges dangerously close to life’s harsher truths. The seashells, once cast upon tables, do not always lie.

The novel’s second epigraph, from Urbano Bettencourt — “The narrator observed the characters for a long time. And was peremptory: I refuse to walk among people like these” — signals Veríssimo’s layered irony. Irony upon irony. Humor upon humor.

At once a tragedy of lost love and impending death, and a comedy in many of its pages, The Happiness of Imperfect Things is among the most distinctive narratives of our time. It transcends its own geography to become one of the most compelling Portuguese-language novels published in recent years — a work that stands both firmly within our tradition and boldly beyond it.

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.