On David Oliveira and His Poetry

By Vamberto Freitas

There are writers whose biographies resemble footnotes to their work, and others whose lives seem to have been drafted in the same ink as their poems. David Oliveira belongs unmistakably to the latter category. Among Luso-American writers, his trajectory is singular—not merely for its geography, but for the moral and imaginative latitude it has demanded.

I first met him in 2001 at Yale University, at a conference marking one hundred years of Portuguese immigrant literature in the United States. He already possessed a substantial body of work—though scattered across some of the country’s most respected journals—and had published a slender volume, In the Presence of Snakes, whose title poem I later reviewed and discussed in one of my own books. Born in Hanford, in the agricultural heartland of California’s San Joaquin Valley, Oliveira grew up among Azorean grandparents and parents devoted to farming and livestock, like so many of our people in that era. Yet he soon departed that inland terrain for Santa Barbara, trading furrows for the Pacific horizon, and placing himself in one of the most cosmopolitan environments of the University of California system.

There he founded Solo, a literary magazine that would receive national recognition, and later the Santa Barbara Poetry Series, which continues to this day. In 1999 he was named Poet Laureate of Santa Barbara—the city’s “Millennium Poet.” Then, in 2002, he vanished from the American literary radar, relocating to Phnom Penh, Cambodia, where he became a professor at Pannasastra University. It was only recently that I heard from him again, when he called to say he would be spending several days in Ponta Delgada with a companion from his adopted country, following what I imagine was a long journey across America and continental Portugal. Our conversation on a café terrace along the marginal avenue remains one of my enduring pleasures.

Of the two volumes he placed in my hands—As Everyone Goes (2017) and A Little Travel Story (2008)—it is the latter, with its Asian-inflected cover, that demands attention here. It is a book divided between origins and arrival, between the remembered landscape of California and the lived immediacy of Cambodia. Its first half gathers poems of family memory and Portuguese-American inheritance; its second half bears witness to a radically different cultural sphere, a nation that endured the unspeakable terror of Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge, and that had earlier been savagely bombed by the United States during the Vietnam War.

Oliveira’s poems do not lecture; they narrate. They unfold in a free verse of supple cadence, never careless, never slack. Each word bears its weight—ironic, at times ambiguous, often layered with that rare polysemy which our own literary circles seldom risk. In the first section of the book, one encounters an extraordinary poem titled, in Portuguese, “No Vinho a Verdade.” There, the poet recalls moments with his Azorean grandfather, who instructs him in the beauty of wine and the proper way to drink it. It is not sentimentality, but initiation: into taste, into lineage, into a certain Mediterranean ethic of pleasure tempered by restraint.

From there, Oliveira moves with ease between private and public memory. Poems such as “The End of the 20th Century,” “President Clinton Lifts Ban on Gays in the Military,” and the mordantly comic “Jerry Falwell Contemplates Oral Sex” reveal a poet alert to the hypocrisies and convulsions of American culture. The latter piece skewers an evangelical televangelist whose weekly program I myself once watched—if only for what Americans call comic relief. Oliveira’s satire is not cruel; it is clarifying. His poetry refuses to accept the American refusal: the denial of difference, the policing of sexual orientation, the anxious puritanism disguised as virtue.

And yet, when he turns to Cambodia, the tone shifts without abandoning its core humanity. The Mekong becomes not exotic spectacle but lived environment. Neighbors—some observed from a distance, others embraced in intimacy—enter the poems not as anthropological curiosities but as mirrors. Geography dissolves. The poet’s great gesture is eliminative: the erasure of distance between “us” and “them.” In a land nearly annihilated by the Khmer Rouge, he discovers not barbarism but the fragile civility of a people rebuilding, quietly, with dignity.

“Any place is like every place,” he writes in the book’s final poem:

And this is where I am.

It is afternoon,

to give the place time,

and it is summer,

to give the place a history.

It would be facile to read this as cosmopolitan relativism. It is something deeper: a metaphysical assertion that place is less destiny than condition, that history becomes legible only when we inhabit it with attention. Oliveira’s poetry does not indulge in overt political commentary about Cambodia; he reserves his sharper critiques for the United States. But even there, he does not condemn his compatriots wholesale. He registers injustice—toward immigrants, toward people of color, toward those deemed undesirable—without surrendering to bitterness.

His sensibility recalls, at moments, the troubadours of an older Europe: mocking power while safeguarding the soul of the common day. There is in his verse a robust empathy, an insistence that survival itself is an act of resistance. He refuses the obscurantist tendencies of certain contemporary poetries—the private symbols, the hermetic metaphors that conceal a poverty of thought. Great poetry has never depended on opacity for its authority. It depends on vision.

Oliveira was a student of Philip Levine at California State University, Fresno—a lineage that matters. Like Levine, he understands labor, exile, and the moral density of ordinary lives. His inclusion in canonical anthologies such as A Near Country: Poems of Loss and The Geography of Home: California’s Poetry of Place confirms what attentive readers already know: his work participates in a broader American meditation on displacement and belonging.

For those of us who inhabit cultural and national hybridity—as I do, and as he does—Oliveira’s poetry offers neither resolution nor consolation. It offers recognition. The Mekong and the San Joaquin, the Azorean vineyard and the Cambodian riverbank, the evangelical broadcast and the café terrace in Ponta Delgada—all coexist within a single moral imagination.

In that sense, A Little Travel Story is misnamed. It is not little. Nor is it merely travel. It is an inquiry into what it means to be at home in a world that has burned and rebuilt itself many times over.

—

David Oliveira, A Little Travel Story. Harbor Mountain Press, Brownsville, Vermont, 2008.

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

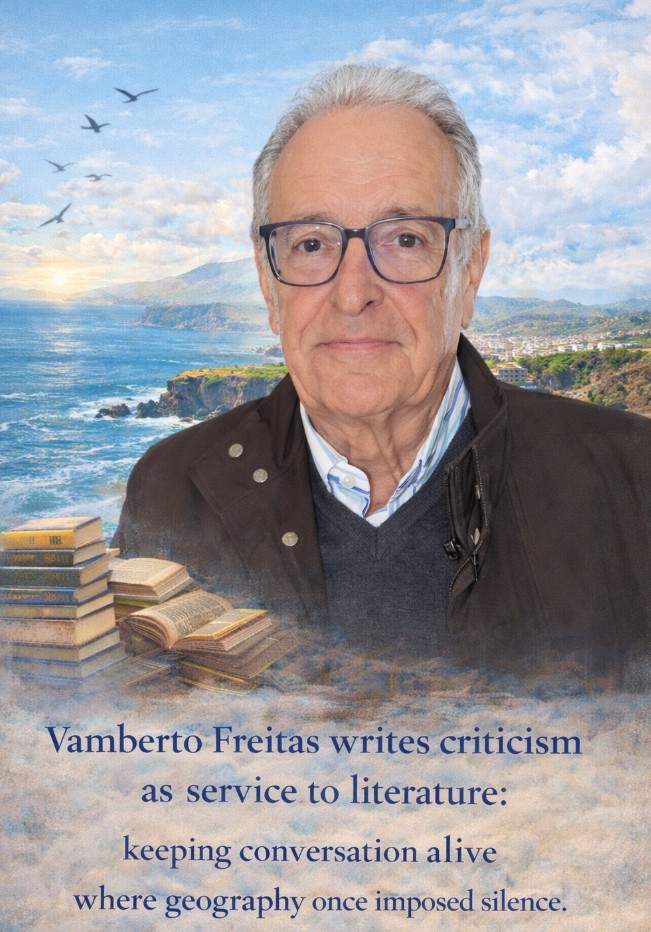

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.