THE AZOREAN PRESS IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY (4)

There was a moment in the nineteenth century when the Azores began to speak in ink.

Before cables stitched the Atlantic floor, before steamships shortened the distance between islands and continents, there were small presses—wooden, stubborn, creaking in damp rooms—turning out fragile sheets of paper that carried argument, poetry, rumor, ambition. From Terceira to São Miguel, from Faial to the far-flung Flores, the islands discovered that they could answer themselves in print.

As we have seen, the first newspapers appeared island by island between 1830 and 1885: Chronica da Terceira in Terceira; Chronica in São Miguel; O Incentivo in Faial; O Futuro in Graciosa; O Jorgense in São Jorge; O Picoense in Pico; O Mariense in Santa Maria; and O Florentino in Flores. Only Corvo, the smallest and most solitary, would remain without its own early paper.

It is worth lingering with these pioneers.

On April 17, 1830, in Angra do Heroísmo, Chronica da Terceira was born—the first newspaper printed in the Azorean archipelago. It was an official organ of the Regency, issued weekly and produced at the Government Press. Its life was brief but decisive: forty-four issues, ending on March 27, 1831. Among its editors were Simão José da Luz, Elias José de Moraes, José Estevão Coelho de Magalhães, and João Eduardo d’Abreu Tavares—men who understood that print could stabilize a moment of political uncertainty and give it narrative shape.

Two years after the press arrived in the archipelago, Ponta Delgada answered with its own weekly, Chrónica, founded in 1832. Likely the first newspaper printed on São Miguel, it marked the beginning of that island’s quantitative leadership in nineteenth-century Azorean publishing. Ponta Delgada would become, in time, the most prolific voice among the islands, its presses humming with political and literary debate.

On January 10, 1857, Faial entered the conversation with O Incentivo, the first newspaper printed on the island. Owned, edited, and written by João José da Graça Júnior, this “literary and news” weekly operated out of its own press on Rua do Colégio, No. 2, in Horta. It lasted little more than a year, closing in April 1858, yet it marked the beginning of Faial’s journalistic self-awareness.

Graça Júnior’s restless energy carried him further. On August 4, 1866, in Santa Cruz da Graciosa, he founded O Futuro, a self-described political newspaper. Printed in its own typography shop, it survived barely a month, ending in September when its owner relocated to Faial. Even so, the title—The Future—felt prophetic. The islands were imagining themselves forward.

São Jorge joined the printed world on February 15, 1871, with the biweekly O Jorgense, launched in Velas. Political, literary, and news-driven, it was directed by A. S. B. Silveira and edited by José Urbano d’Andrade, with Dr. João Teixeira Soares as a principal contributor. Printed in its own press, it endured until November 15, 1879, reaching issue No. 195 before suspending publication—a respectable run in an era when ink and paper were always precarious.

In Madalena, on Pico, O Picoense first appeared on December 20, 1874, founded by its editor Urbano Prudêncio da Silva. Printed on Rua da Calheta, it ceased publication on May 27, 1877. The rhythm was familiar by now: ambition, argument, exhaustion.

By 1885, the press had reached the archipelago’s outer edges. In April, Santa Maria saw the birth of O Mariense, a “literary and news” paper founded on April 9 and edited by Jacintho Monteiro Bettencourt, with Urbano de Medeiros as its writer. Printed at the Tipografia Oriental on Rua da Conceição in Vila do Porto, it was silenced on July 15 of that same year, after only seven issues. The reason was stark: a judicial sentence for abuse of press freedom and the editor’s refusal to publish the ruling. The eighth issue was partially printed—only the first and fourth pages—before authorities prohibited its release. Even in the Atlantic’s relative isolation, the struggle between expression and power was immediate and real.

That same summer, on July 2, 1885, Flores inaugurated its own voice with O Florentino, founded in Santa Cruz. Initially weekly, later tri-monthly, it was driven by Constantino Cândido Leal Soares, who would eventually leave to found another paper, Amigo do Povo. Printed at the Tipografia Imparcial Florentina, O Florentino published its final issue in 1888.

This, then, is the portrait of the Azorean press in the nineteenth century: fragile, local, political, literary—born of necessity and conviction. From Santa Maria to Flores, each island claimed the right to narrate itself. The presses were modest; the aspirations were not.

The Azores entered modernity not only through ships and telegraphs, but through the quiet insistence of ink.

(To be continued)

—

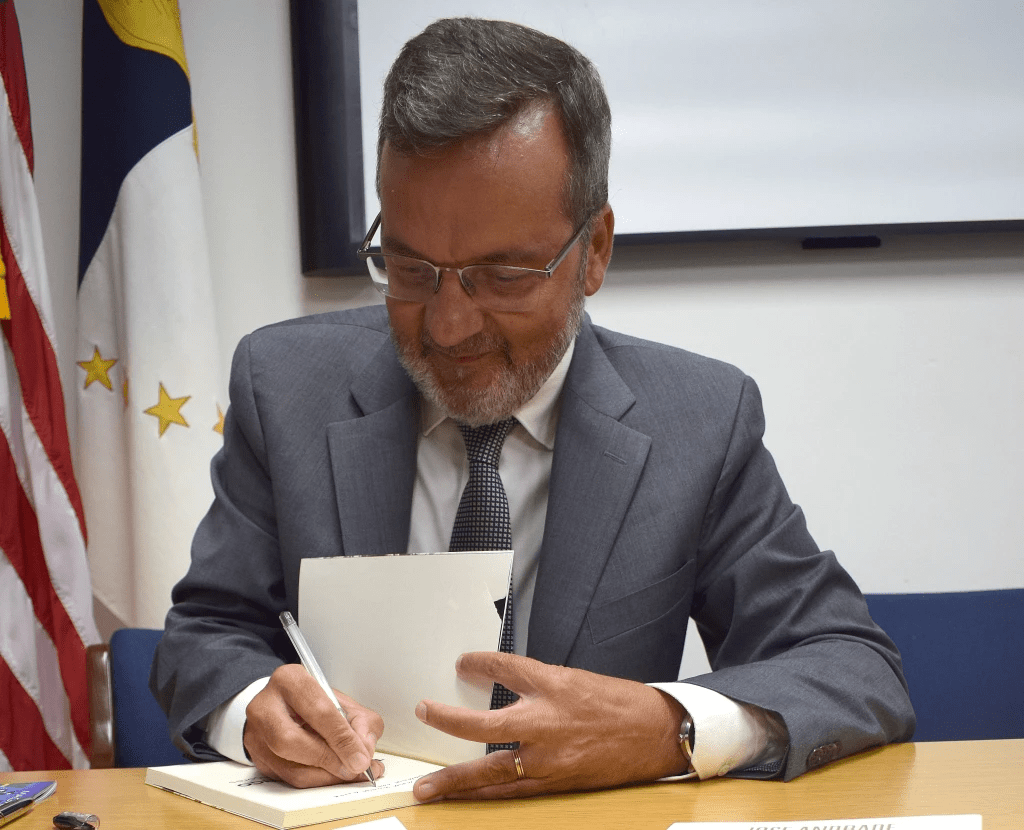

José Andrade is the Regional Director of Communities, Government of the Autonomous Region of the Azores.

This chronicle is based on the lecture “Toward a History of the Azorean Press,” delivered at the Public Library of Angra do Heroísmo, July 3, 2025.