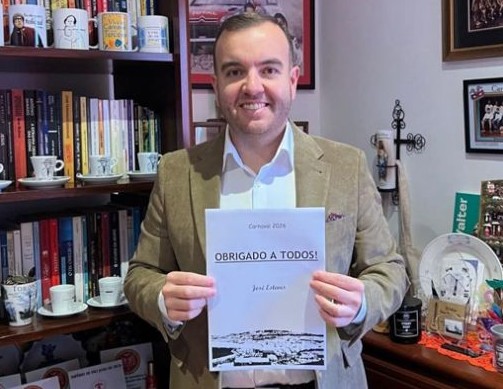

JOSÉ ESTEVES, WRITER OF CARNAVAL DANCES

With Carnaval just around the corner and rehearsal halls already humming, José Esteves sits at the center of one of Terceira’s most cherished traditions: the writing of danças and bailinhos. Thoughtful, measured, and quietly passionate, Esteves reflects on the craft, the responsibility, and the enduring vitality of a celebration that remains, above all, the people’s voice.

Carnaval is at the door, and the groups are already rehearsing. How many themes and songs did you write this year, and how do you assess this “marathon”?

This year, as in 2025, I wrote themes for 10 groups. That is the numerical limit I set for myself, so I could give proper attention to the creation of each piece. Of those ten, seven were complete works—I wrote both the theme and the songs for the group. In addition to those seven, I wrote songs for four other bailinhos.

This year’s Carnaval carries a special meaning for me. For the first time, I had the opportunity to write for my own group. As an author, I had long felt that curiosity and desire, but only now—with the return of the Bailinho do Centro Social do Juncal—did that possibility arise.

The year 2025 brought new responsibilities into my life, which meant less free time for writing. That made this “marathon” even more demanding in terms of organization. Still, I see it as a positive experience. I met every deadline and gave myself fully to each project.

Can we expect a great deal of social criticism? What themes will be addressed this year?

Carnaval, from its origins, has always been the voice of the people, and so social criticism is naturally part of its fabric. Several groups focus exclusively on that register. Among the ones I write for, Baile Delas has, since its creation, embraced that approach. Personally, I find that type of writing deeply satisfying.

As the year unfolds, we begin to sense which events will inevitably find their way onto the Carnaval stage. This year, for example, there are the controversies surrounding the bullfighting ropes, the uproar around local and presidential election campaigns, the roadwork at the Miradouro do Raminho, and many other issues—some local, others global in scale.

Carnaval captures them all. It listens. It remembers. And then it sings.

You also wrote the theme for the Dança de Espada of Lajes. Does that carry a different weight? Do you feel you are helping preserve a genre at risk of disappearing?

Writing for the Dança de Espada of Lajes carries a different emotional weight, especially because of the delicacy and immediacy of the themes being staged. As an author, I immerse myself in the history and feel the characters’ pain almost as if it were my own.

It is a kind of writing I take particular pleasure in, perhaps the register where I feel I achieve my strongest work. I feel honored to contribute to a dance that has played a crucial role in dismantling the notion that sword dances are overly long or tedious. By addressing contemporary issues, these performances reach the audience’s heart more directly than when the themes were primarily historical or religious.

I do not believe this genre will ever entirely disappear from Carnaval, though sword dances will always be fewer in number. This year, the Dança de Espada from Vila das Lajes brought its work to Diaspora stages, and we will also welcome a Dança de Espada from Hilmar, California. Both groups include many young members, which gives us hope thatthis tradition will continue to be appreciated and performed for many years to come, both on Terceira and in our communities abroad.

Nearly 60 dances and bailinhos are expected on Terceira’s stages this year. Is Carnaval still thriving? Has it maintained its quality?

The sheer number of dances and bailinhos is itself a clear indicator of Carnaval’s vitality. Each year, we see more young people joining the groups, a sign that the longevity of this celebration is not under threat.

In all honesty, I believe Carnaval has grown enormously in quality. Costumes are richer. Musical interpretations are more refined. The staging of themes is more carefully developed. The vocal quality of performers is extraordinary. And beyond that, the logistics—the movement of groups from place to place, the organizational capacity of the hosting societies—have improved significantly. All of this has allowed Carnaval to evolve and to draw ever larger audiences to the stage.

Rhyme is one of the defining features of these popular theater forms. With new authors emerging in recent years, do you believe it can be sustained into the future?

I have no doubt. Rhyme is what sets these manifestations of popular theater apart. It gives them a singular beauty.

The people of our island live hand in hand with poetry—from Carnaval to the marchas, from folklore to pezinhos and improvised singing. There is a natural facility here for creating strong, rhymed work.

In recent years, several new authors have emerged in Carnaval, and it is interesting to note that many of them, like myself, are also popular improvisational singers. That alone assures us that rhyme will remain alive in the texts of bailinhos and dances.

I think of colleagues such as Samuel Borges, Samuel Martins, Fábio Ourique, and Ricardo Martins, who have distinguished themselves as writers while building careers as improvisers. And it would not be right to speak of Carnaval without mentioning names like Hélio Costa, João Mendonça, and Jorge Rocha—figures who were and will always remain references for us as authors.

They were fountains from which we drank wisdom and inspiration as we grew. They helped elevate Carnaval to a level of excellence.

And I must also remember Álamo de Oliveira, who will always be cherished as one of the most beloved popular poets among lovers of Carnaval.

In Diário Insular-José Lourenço-director

Translated and edited by Diniz Borges.