Circling Home: A Conversation with Vamberto Freitas

February 27, 2017

Is the literary critic an endangered species?

Victor Rui Dores, Conversas Açorianas

By Vamberto Freitas

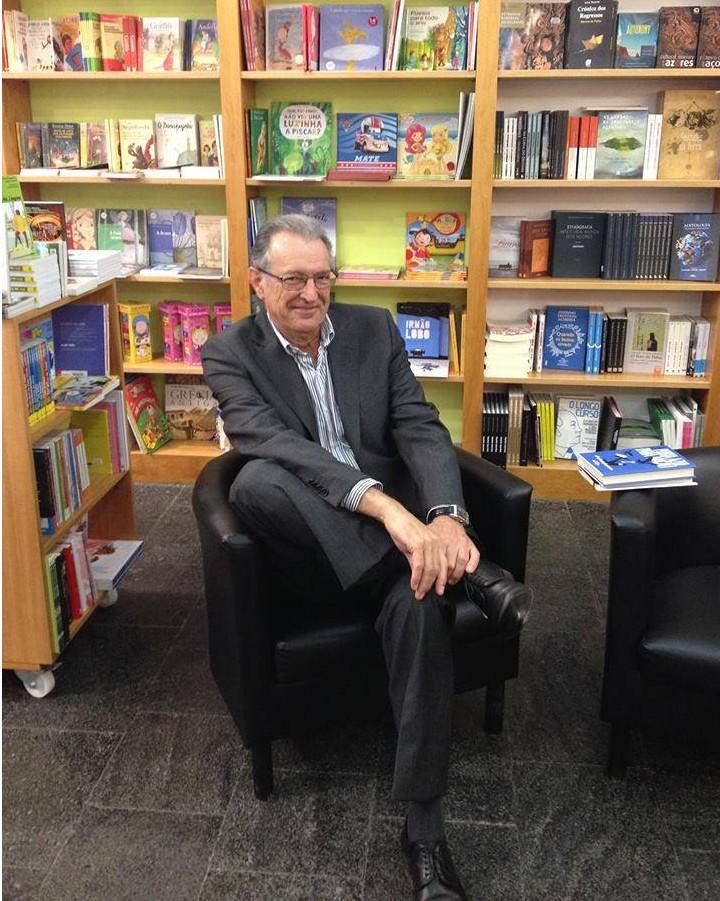

University professor, intellectual, essayist, literary and cultural critic, columnist, and translator, my guest today is synonymous with an essayistic vocation cultivated with passion, and with serious literary criticism generously shared. He is an author of keen aesthetic sensibility and creative capacity, theoretically well equipped, able to inform, clarify, interpret, and evaluate—bringing into his cultural discourse the methods and concerns of diverse branches of essay writing and literary scholarship.

Decades of sustained critical labor have made him one of the most important scholars of North American literature and of Azorean literary expression. Today, I’m sitting down for a conversation with the Terceiran Vamberto Freitas.

Victor Rui Dores: Welcome to the program, Vamberto Freitas. It’s a pleasure to have you here. Is the literary critic an endangered species?

Vamberto Freitas: No. At most, we’ve become irrelevant in a context dominated by criminal banks, money, and the petty obsessions of a stupid and odious ruling class—without values, without dignity, and certainly without sensitivity for everything else that makes us human and deserving of life.

VRD: You are widely recognized as a major essayist. In newspapers, books, and public forums, you study authors on both sides of the Atlantic with remarkable consistency. On average, how many books do you read per month?

VF: It depends. Generally, about four. Some weeks I read less, others more. During the summer holidays, I usually return to Açoriano Oriental—and now also to the newspaper I and the weekly SOL—with five or six pieces already written. That gives me some breathing room.

VRD: What defines a good book for you?

VF: For me, literature and society are inseparable. A good book is either an artistic representation or a poetic reimagining of its place and time—or else a substantial essay, or collection of essays, that reinterprets that same time and place, whether it’s our street or the entire world.

VRD: Do you only write about books you like unconditionally?

VF: Yes. Some years ago, I decided life was too short and the world—especially the Portuguese-speaking world—is full of great books and great literature. The rest doesn’t harm anyone, but I don’t pay it attention. Naturally, I don’t have time to write about many excellent books that are essential references for me.

VRD: You were born in Fontinhas, on Terceira Island, and in 1964, at age thirteen, you emigrated with your family to the United States. At California State University, Fullerton, you earned a degree in Latin American Studies and a specialization in English. You taught languages and literatures in American secondary schools while working extensively with community newspapers, Portuguese-language radio, and organizing statewide conferences on bilingual education and immigration. For many years, you were a correspondent and contributor to the literary supplement of Diário de Notícias (Lisbon). Where does the unavoidable figure of Onésimo Teotónio Almeida enter your life?

VF: In the mid-1970s, at a conference on Luso-American education in California. I believe it was the last one attended by Jorge de Sena, in 1978. One of my first critical essays, published in Portugal, was about Ah! Mònim Dum Corisco, by Onésimo, published in the now-defunct journal A Memória da Água-Viva, then edited by Urbano Bettencourt and J. H. Santos Barros. From that moment on, Onésimo became—beyond being a dear friend—one of my greatest intellectual influences and references.

VRD: Who else shaped your literary formation? Which authors influenced your essayistic work?

VF: First and foremost, the great Edmund Wilson. Then George Monteiro and my late professor and mentor Nancy T. Baden. Among the Portuguese, João Gaspar Simões, Eduardo Lourenço, Teresa Martins Marques, and in recent years, Professor João Barrento. In a more strictly literary register, Eugénio Lisboa—among many others, of course.

VRD: For love of a woman—Adelaide Freitas—you returned to the Azores, settling on São Miguel, where since 1991 you’ve served as Lecturer in English at the University of the Azores. Between 1995 and 2000, you also played a central role in cultural journalism by founding and editing the SAC – Suplemento Açoriano de Cultura in Correio dos Açores, a project that allowed you to study Azorean literary imaginaries and helped affirm Azorean cultural identity. Do you ever regret returning to the islands?

VF: Never. I wouldn’t trade my Azorean islands for any other place in the world. From the beginning, here on São Miguel, I experienced forms of friendship and affection I had never known anywhere else I lived.

VRD: With the rise of new communication technologies, newspapers have largely abandoned cultural supplements and dedicated spaces for literary criticism. Locally, the exception is Açoriano Oriental, where you maintain a literary and cultural column, borderCrossings: Transatlantic Readings, which has resulted in three volumes. You also co-edit the literary page Artes & Letras with Álamo de Oliveira. This work doesn’t pay the rent…

VF: No. But it’s my obligation to contribute to the creative and literary archives of my land—and of my country as a whole. I earn my living as a university professor, which sustains my existence as a teacher and essayist.

VRD: Let’s look at your other books.

VF: They are my contribution to the literary record—of my time and of the places I’ve lived. Others must judge their value. I can say that I feel deep gratitude for what has been written about my work in Portugal, the United States, and Brazil.

VRD: We live in a time when literary taste is giving way to literary fashion. “Cultural reporters” now form lobbies in the mainstream press, aspiring opinion managers, often part of the capital’s literary jet set. They don’t offer aesthetic judgment, just reading notes. Worse still is a certain academic criticism—hermetic, inaccessible, wrapped in self-consuming hermeneutics. You avoid both paths, and I want to praise you for that. You also write in a vibrant Portuguese, with clarity, lexical precision, and strong conceptual articulation. Is that due to your Anglo-American training?

VF: Not exclusively, but I believe my American education was the primary influence on my writing.

VRD: Have you ever been tempted to try narrative fiction? Some say literary critics are frustrated novelists…

VF: No. I’m not a frustrated novelist. Just frustrated.

VRD: Public recognition of your work came in 2015, when the Azorean Legislative Assembly awarded you the Autonomous Insignia of Professional Merit. And now, Vamberto?

VF: Now I’ll continue working with even greater energy and responsibility in the critical dissemination of our culture and literary tradition. I’m deeply honored and grateful that the highest representatives of our people recognized my work. Believe me—an official gesture from home outweighs everything else.

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.