As night falls over Terceira Island, the basalt fields darken, the wind persists, and the Atlantic resumes its ancient breathing. Across the archipelago, lights appear one by one—small, steady gestures against immensity. It is the hour of memory in the Azores, when the islands fold inward, carrying centuries of departure, prayer, and endurance.

At that same moment, in California—where the sun stands high and the day is fully awake—the descendants of those islands move through fields, churches, dairies, and cities. It is midday here, in the land that would come to host the largest Azorean community in the diaspora. Between dusk and noon, between island shadow and continental light, stretches the Atlantic bridge that shaped the life and work of August Vaz.

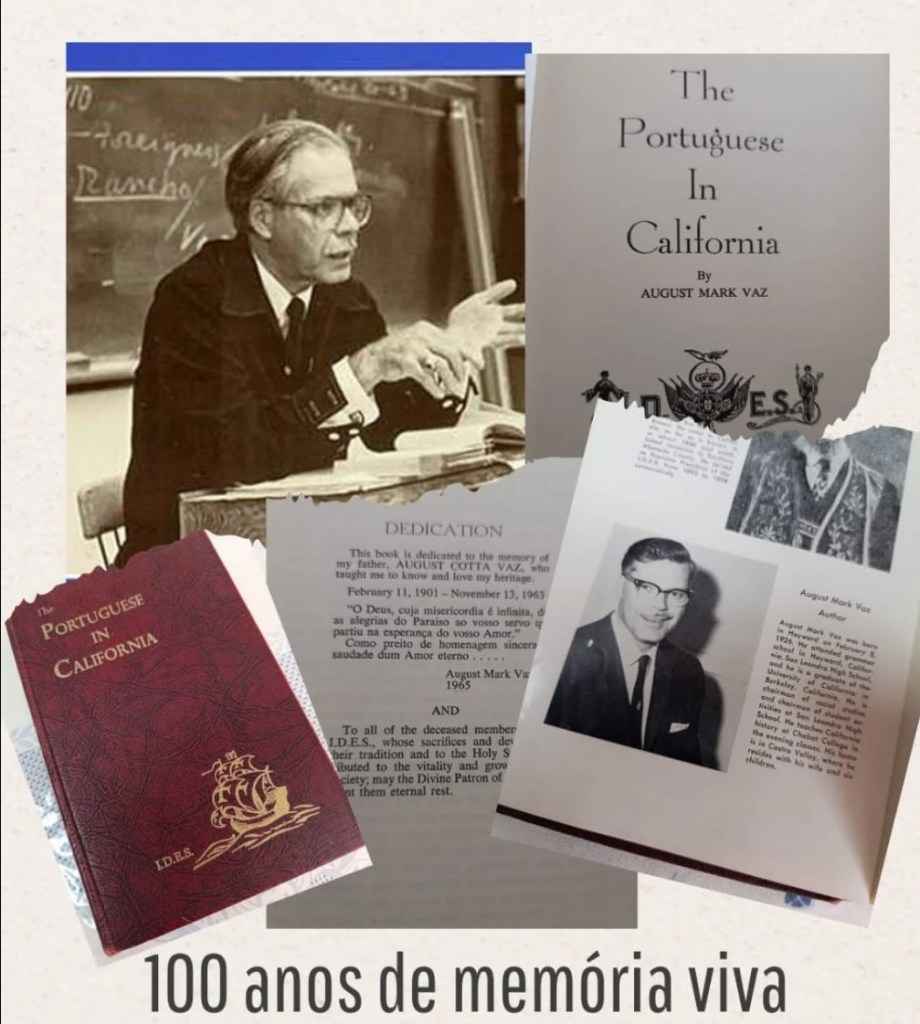

Born on February 8, 1926, August Vaz entered a world that could not yet imagine the California he would one day help explain to itself. A century later, his life reads as a quiet cartography of migration, education, and belonging—drawn not through spectacle, but through patience, discipline, and an unwavering respect for memory.

Vaz belonged to a generation that understood history not as abstraction, but as lived experience. He was shaped by departure and arrival, by the pull of ancestral islands and the demands of a new continent. A proud descendant of Terceira, he carried insularity not as limitation but as ethical orientation: attentiveness to community, endurance, and continuity. Terceira was never merely a place of origin; it was a moral geography that informed how he taught, how he wrote, and how he understood the Portuguese presence in California.

For decades, August Vaz taught history in a California high school, where he earned not only professional respect but genuine affection from generations of students. He was not a conveyor of dates and names; he was a cultivator of attention. Students remember him as demanding but fair, rigorous yet generous—someone who believed that education was not preparation for life, but life itself. In classrooms often indifferent to immigrant narratives, he insisted—quietly and persistently—that the stories of working people, of newcomers, of communities on the margins, mattered.

Teaching, for Vaz, was inseparable from citizenship. To teach history was to confer dignity, especially upon those whose pasts had been excluded from official narratives. This conviction found its most enduring expression in his landmark book, The Portuguese in California, published by the IDES in 1965.

Appearing at a time when Portuguese-American studies were still in their infancy, The Portuguese in California was neither a nostalgic chronicle nor a folkloric celebration. It was a sober, methodical, and deeply humane act of documentation. Vaz approached the Portuguese presence in California as both historian and witness, attentive to economic structures, migration patterns, labor conditions, and community institutions. He wrote with restraint, but also with empathy—refusing caricature, resisting simplification.

What gives the book its lasting force is not only its pioneering status but also its tone. Vaz did not romanticize hardship, nor did he elevate immigrants into heroic archetypes. He understood them as complex actors navigating a difficult social landscape—fishermen, dairy farmers, laborers, small entrepreneurs—men and women whose lives unfolded within constraints of class, language, and power. In doing so, he produced something rare for its time: a Portuguese-American history that was neither apologetic nor defensive, but confident in its factual solidity and moral worth.

The book also revealed Vaz’s teaching instinct. Written with clarity and discipline, it was meant to be read not only by scholars but by students, teachers, and community members seeking to understand their own place in California’s story. It bridged academic inquiry and public history long before such crossings became fashionable. In many ways, The Portuguese in California was an extension of the classroom—a lesson offered to the broader civic world.

August Vaz never sought prominence. His influence was cumulative rather than spectacular, built through years of teaching, writing, and quiet mentorship. Yet his legacy is unmistakable. He helped lay the foundations for Portuguese-American studies with intellectual honesty and ethical care. For those who came after him—researchers, writers, educators—his work offered not only information but a model: scholarship rigorous without being distant, committed without becoming ideological.

What ultimately endures, however, is the book itself—not merely as an academic contribution, but as an act of historical justice. At a time when Portuguese immigrants had labored for generations largely unseen—their names misspelled, their stories unrecorded, their contributions absorbed into anonymity—Vaz gathered the scattered threads of a community and wove them into a narrative. He did not shout. He did not plead. He documented. And in doing so, he made presence irreversible.

That book did something quietly radical. It named a people who had been there all along. It traced their footsteps through fields and fisheries, through dairies and neighborhoods, through churches, halls, and kitchens where history was spoken softly, if at all. Vaz understood that silence is not the absence of history, but the product of power—and that to write is to interrupt that silence. Page by page, The Portuguese in California transformed invisibility into record, memory into archive.

For many readers—especially those raised in families accustomed to endurance rather than recognition—the book offered something rare: confirmation that their lives belonged to history. That their parents and grandparents were not footnotes but actors. That their work mattered. That they, too, were part of California’s story. In this sense, August Vaz did not merely write a book; he opened a door through which a community could finally step forward and be seen.

As night settles again over Terceira and the Azores, and another midday unfolds in California, the Atlantic continues its slow conversation. Across that distance, August Vaz’s work still travels—carrying voice where there was silence, light where there was shadow, and recognition where there was once only endurance.

That is the enduring power of his contribution: not nostalgia, but presence; not noise, but voice.

We honor his legacy and his work on his 100th birthday.

Diniz Borges