From the Island of Flowers, with Beauty and Art

September 2, 2022

Vamberto Freitas

Cruel destinies. Blood-scored lines carved into lost horizons. Furrows of pain etched across shattered dreams.

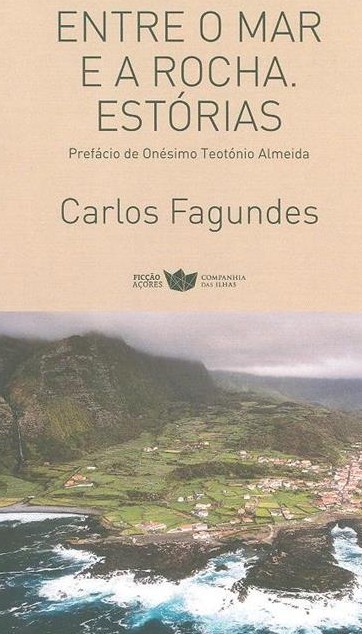

Between the Sea and the Cliff. Stories, by Carlos Fagundes

For all these years, some of us were unaware of the writing of a truly refined Azorean author. His prose appeared sporadically on a blog, quietly, almost furtively. A Florentine by origin, Carlos Fagundes was born in Fajã Grande in 1946, studied for the priesthood in Angra, later worked in several areas of education on mainland Portugal, and now resides on Pico Island. All of this—and more—appears in the lucid and illuminating preface by Onésimo Teotónio Almeida to Between the Sea and the Cliff. Stories, recently published. I will not rehearse those opening pages here. It is enough to say that it was the well-known writer and Brown University professor who urged Fagundes to commit these words to paper.

Some in our literary generation have always understood this task: not to leave anyone stranded in limbo—because limbo, paradoxically, can be full of invisible grandeur, awaiting only the flight that brings it into the shared realm of readers willing to receive it. As readers quickly realize, despite the title, these are not “stories” in the sense of invention, but histories—rooted in the firm memory of a life, a place, a time. That is precisely the nature of Fagundes’s prose. Memory, as we know, can be unreliable, even treacherous. None of this, however, diminishes the clarity or seductive beauty of his writing.

The brief epigraph I borrowed from the final page of the book captures both the pain and the lived adventure of what rural life once meant on a distant Azorean island—where the only radical salvation was America, glimpsed as a lost paradise, yet one to be found by all who refused to accept centuries-old archipelagic poverty, backbreaking labor on land and sea, and the occasional fury of unpredictable Nature. Few books succeed so vividly in placing us before other realities and other people, in eras forgotten by most who never lived them—and even more so by those who lack curiosity about their own origins. Other people’s gardens always appear more alluring, more “interesting.”

These are not tales of lamentation, nor of heroism. The narration remains in the first person, at once intimate and distant, leaving readers free to interpret according to their own lived experience or reading histories. Each of us carries an individual and family story: modest Azorean settings where prosperity and poverty coexist—sometimes without resentment, sometimes with the clear awareness that there is more world within and beyond the horizon. A sense of social justice runs through this prose, though it is attributed to powers beyond reach. Communal life is accepted as given; initiative and courage emerge in the “characters” without overt rebellion. America, once again, is always just there—near enough to imagine. It saved the weak and unimaginative Azorean elites from far more violent upheavals.

Between the Sea and the Cliff. Stories can be read in any order—randomly or sequentially. Fagundes’s writing is as clean as the surrounding Azorean sea, like the cultivated or wild lands of those years. The movement of the lives revisited here is wrapped in linguistic mastery that holds the reader in a sustained moment of that much-invoked “pleasure of the text.” Each sentence, on its own, brilliantly reflects the moments of those who “look back” at us from the page, inevitably transmitting empathy to those who lived all this on the other side of history—those capable of understanding the “other.”

Most Azoreans come from these origins, lived or observed close to home: not infrequently, the poor finding shelter in the shadow of the Big House of the wealthy landowner—often an unblamable heir to the historical fraud that was Atlantic landholding under the captain-generals. God and ritual softened both believing and indifferent souls alike. A brave people, to borrow a voice now of little consequence. On Flores, there were the harshly worked lands, a few cows and other means of survival, two towns, and a scattering of small parishes and settlements. In front, the sea—bringing and taking: shipwrecks that awakened the bravery and generosity of those who watched from the edge of the surf and gave their lives to save strangers; the now-mythic ships that carried a bit of everything, especially from the dreamed-of America; clandestine escapes by the boldest; the return of emigrants flush with dollars, a kind of revenge against what had once seemed a destiny of misery and servitude; escapes from the siege of love, where men and women challenged the universal hypocrisy of any corner of the world. Poor houses, rich souls.

Allow me one interpretive audacity: this book stands—opinions being opinions—shoulder to shoulder with any award-winning fictional work of recent decades. Between reality and fiction, Fagundes begins with a life of hardship, memorializing himself and others, then allows his imagination to act as an omniscient narrator, assigning thoughts, feelings, and motives to all who populate his prose. The chronicle is a hybrid form; it permits this creative manipulation of language, image, and memory. The mirror, in the end, also faces the reader—here or anywhere—land, sea, and people in daily struggle, accepting the dominion of God while attempting to ignore the rule of socio-economic power.

At moments, the prose recalls the magical realism of certain writers. I leave that recognition to others. One of them, Gabriel García Márquez, once said he never invented anything—only the reality he had personally witnessed, or that his community claimed as its own: its beliefs and unquestioned fantasies.

“No one ever knew to whom,” writes the narrator in one story, “Bigorna confided his secret. But as it passed from mouth to mouth, the entire parish soon learned what had happened on that iniquitous dawn: Bigorna crossed paths on the Covas slope with a woman, young and beautiful, whom he did not recognize. Turning back out of curiosity, he followed her for a few seconds and realized she was naked. Then the woman turned as well, and Bigorna, frozen with fear, saw that from the waist down her body was covered in black hair like a goat’s, and her feet—those were exactly the feet of a goat.”

Here is yet another work that brings us the rural world of Flores in its singular geographic and human context—the extreme western edge of Europe, surviving, and in the 1950s and ’60s always looking westward for salvation. It is impossible not to read it, beyond its specific lived experiences, as a luminous mirror of all the Azorean islands: rurality as invention and reinvention across generations since settlement; urbanity as little more than an imitation of what is imagined to be the grandeur and existential weight of continental centers or larger islands.

Flores had already given us, in the last century, other major poets and fiction writers. For now, we are left with three literary modes through which each author has offered searing visions of a native island—and, ultimately, of all of us: the inner siege of the archipelago, the historical flight toward America, and, from time to time, toward cold northern seas in search of bread and fish. Between the Sea and the Rock. Stories, I believe, will endure as another lasting reference in Azorean literature—provided future generations do not forget their troubled mid-Atlantic origins.

—

Carlos Fagundes, Between the Sea and the Cliff. Stories. Lajes do Pico: Companhia das Ilhas, 2022.

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.