On February 20, 1909, the Italian writer Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published the Manifesto of Futurism in the French newspaper Le Figaro, launching what he proclaimed to be “a new literary and artistic movement.” Its echoes spread quickly across Europe at the dawn of a century defined by acceleration, when the modern city, the machine, and speed were becoming the dominant symbols of a rapidly transforming age.

The manifesto rejected aesthetic tradition and championed an “Art of Action,” closely aligned with progress, urban energy, and the cult of movement. It was a call to break with the past and to embrace the dynamism of the industrial world.

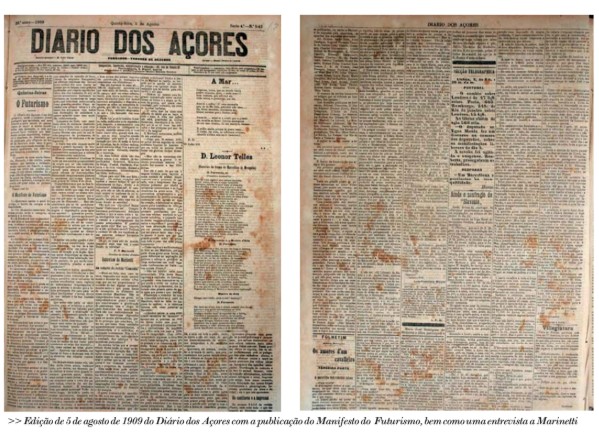

That same year, remarkably, the manifesto found one of its earliest printed receptions in Portugal—not in Lisbon, but in the Azores. The text became known in Portugal in 1909 through a translation by Luís Francisco Bicudo, published in the Diário dos Açores on August 5 of that year.

The newspaper’s engagement went beyond simply printing the manifesto. The Diário dos Açores also published an interview with Marinetti, amplifying the significance of the event and placing the archipelago on the early routes of Futurist circulation in the Portuguese language. This editorial decision is widely recognized as marking the beginning of a “pre-Futurist” phase in Portugal—one that effectively starts with this Azorean publication.

In The Futurist Experience and the Generation of “Orpheu”, scholar Carlos d’Alge highlights the importance of Portuguese artists’ and writers’ connections to Paris, where figures such as Mário de Sá-Carneiro and Guilherme de Santa-Rita were active. D’Alge notes that Santa-Rita was reportedly “entrusted by Marinetti with publishing his articles in Portugal,” playing a key role in spreading Futurist ideas.

After 1909, Marinetti deliberately expanded Futurism beyond literature, recruiting artists from other disciplines and unleashing what d’Alge describes as a “flood” of manifestos addressing painting, music, theater, and more. Between February 1910 and April 1912, this strategy sought to occupy public space and redefine modern art itself. It also helps explain the speed with which Futurism spread.

D’Alge points to the obsessive repetition of the slogan “Marciare non marcire”—“to march, not to rot”—across book covers, pamphlets, and letterhead. This was not accidental, but part of a deliberate propaganda effort and an early form of mass communication deployed across Europe and the Americas.

The European response soon followed. In 1913, Guillaume Apollinaire published the manifesto The Anti-Tradition of Futurism in Paris. Two years later, in 1915, Futurist energy arrived forcefully in Portuguese modernism, closely associated with the early issues of the journal Orpheu and the publication Portugal Futurista.

In Portugal, d’Alge characterizes Futurism’s influence as significant, though not always doctrinally decisive. Many modernist writers preferred to carve out their own paths—most notably through Sensationism—while still absorbing the imagery and rhythms of the industrial world: crowds, electric light, ships, locomotives, and the fascination with mechanical power.

Yet the history of Futurism cannot be reduced to technological euphoria alone. D’Alge emphasizes that after the early manifestos and novels, Marinetti’s work increasingly embraced the defense of war and fascism. From 1914 onward, this ideological dimension profoundly shaped public interpretations of Futurism and its political inscription in the twentieth century.

Still, the historical fact remains striking: just months after its Parisian debut in Le Figaro, the Futurist Manifesto crossed borders and found, in the Diário dos Açores, one of its earliest vehicles of dissemination in Portugal. The manifesto was translated, published, and accompanied by an interview with Marinetti himself—the founder of a vanguard that made speed, the machine, and shock both an aesthetic and a communication strategy for launching “modernity.”

From early on, the Diário dos Açores participated in the circulation of major European cultural currents through a network of correspondents. Its founder and first director, Manuel Tavares de Resende, and later his nephew Manuel Resende Carreiro—who succeeded him as director in 1892 after his death—maintained regular correspondence with intellectuals in Portugal and abroad. These connections placed the newspaper firmly within the circuit of national and international events of its time.

Carlos d’Alge details this network, identifying the stays and relationships that facilitated the importation of Futurist ideas, and underscores the pioneering nature of the August 5, 1909 publication. It is there, he argues, that Portugal’s “pre-Futurist” phase begins—one that anticipates and prepares the modernist confrontation of the following decade.

The reception and transformation of Futurism in Portugal did not follow a single or “pure” path. Instead, contact with Italian manifestos intersected with other avant-garde currents and homegrown experiments, generating a modernist constellation in which Futurism functioned both as catalyst and contested material.

Beyond the manifestos themselves, d’Alge identifies key sources of inspiration in the Cubist experience in Paris and in the exchange of ideas between Mário de Sá-Carneiro and Guilherme de Santa-Rita. These discoveries reached Lisbon, where aesthetic rupture collided with polemics, public caricature, and resistance.

It was in this charged atmosphere that, in 1915, the journal Orpheu made its decisive cultural impact, introducing names and works that would shape twentieth-century Portuguese literature—among them Fernando Pessoa, his heteronym Álvaro de Campos, and José de Almada Negreiros.

In this context, Futurism appears less as a coherent doctrine than as a stimulus and a set of available languages. D’Alge raises the question of whether a truly Portuguese literary Futurism ever existed, or whether what emerged instead was a parallel avant-garde movement that incorporated facets of European Futurism, with Pessoa’s Sensationism ultimately assuming a central role.

Paulo Hugo Viveiros