Urbino de San-Payo and Another Side of the Diaspora

December 31, 2011

by Vamberto Freitas

Oh this great AMERICA in such a small body.

It weighs and weighs, for your abundance is hunger,

you wretched Trás-os-Montes man.

You left—and now you’re stuck with it.

— Plural Transitivo, Urbino de San-Payo

Please pay no attention to the punctuation and lowercase letters that follow; that is exactly how Urbino de San-Payo wrote this other short and magnificent text, included in one of his few books of fictionalized “American” chronicles, Plural Transitivo, published back in the now-distant year of 1982. Throughout his career, content inevitably dictated form: out of a life lived and written he shaped some of the most silent poems (“little cries,” as he once called one of his rare public confessions in the pages of Tribuna Portuguesa) of our collective fate. Poet, playwright, chronicler—Urbino de San-Payo’s work was always made of solitary tremors first felt in the homeland, and then, as a stationary wanderer of sorts, in the Southern Californian abundance where he lived and worked the second half of his life.

He passed away a few days ago in Los Angeles at nearly seventy-eight years of age, but he leaves behind an indelible trace: a rich artistic archive of what it meant to live one’s Portuguese identity with short-lived hope in “dark times,” especially from April 25, 1974 onward—a revolution he experienced intensely from his Eldorado exile—up to our present days of despair and generalized indignity, both in his adopted country and in the one he left behind. His life in the Diaspora was unique among us in every customary sense. A true continental Portuguese, he would draw closer to Azorean communities in the 1970s through the friendship of the university professor and writer Eduardo Mayone Dias, perhaps the most Azorean of all Lisboners. He made his living “working,” alongside his wife and lifelong companion Maria Amélia, in some of the richest and most glamorous homes of Beverly Hills. He wrote his inner pain and his infinite longing for an empire of kindness, never forgetting the shared journey of his people, at home and abroad—the distance and indifference toward any notion of “stature” in the false and pretentious Lusitanian hierarchies, which also ensured the near-obscurity in which the man and his work remained, beyond a small circle of readers (in Portugal, a few prestigious writers among them, including Urbano Tavares Rodrigues) who knew and admired him.

His poetry is partially gathered in Escopro, Barbaramente tu, and Boca Consoante; what he himself called “pomoromance” (poetry and prose) appears in Exorcismos menores and Exorcismos maiores; he also wrote the play O Cavalo de Tróia.

Any words of mine by way of fuller introduction to readers unfamiliar with him would be blasphemous when set beside a brief autobiographical note I found on his blog—significantly titled “Putalândia”—only after receiving news of his death, and which he apparently never developed beyond the lines that follow. Once again, pain and humor join in a perfect balance of the “I” and the “we,” here as throughout all his prose and poetry:

“I was born—he writes characteristically in lowercase, as if wishing to hide from the surrounding world—in Lugar da Rede, Mesão Frio, Alto Douro, Portugal. I grew up between the Civil War and the other one, the Great War, where Hitler played his chess of death. Between stealing pears from neighbors’ orchards, roaming the Douro River, and general hunger, I made myself into a little man. Once there, fourteen years more or less accounted for, they put me—without my say-so—on a cattle-car train bound for the Seminary of Santarém, where my destiny in the priesthood was to be decided. My road through the seminaries lasted six years. I served eighteen months as a desk soldier. I wore out the seat of my pants in the civil service and in cafés. In 1968 I took off for London. Two years later I emigrated to the United States, where I now live.”

I met Urbino and we became friends in the days when April still felt like the Spring of Everything. Our companionship unfolded as easily at a Holy Spirit festival in Artesia or Chino as in the Beverly Hills house where his wife worked and he pretended to help while we drank beer at the kitchen table or out back among sculptures belonging to the owner of—imagine this—Universal Studios. It was there, I believe, that I first saw an original by Jackson Pollock, and a wardrobe where each garment bore not only the maker’s label but also its insurance policy! I never saw the lady of the house, but I did witness Urbino being summoned to the living room or bedroom where she lounged—so he could explain some passage of a book she was reading. She even told her friends, with pride, that her employee was a poet and an intellectual. Life’s great ironies, indeed; the Greeks, after all, were once brought to Rome to do precisely the same. Some Lisbon writers told him they would trade places with him without hesitation. What better condition, what better life, for a writer?

One day, I will tell the story of when he took Onésimo Teotónio Almeida and meto Elton John’s house in Beverly Hills—formerly, I believe, Greta Garbo’s—for a party of Portuguese only. The owner was in London, and his housekeeper was none other than Urbino’s very Portuguese sister-in-law. I recount all this not only out of longing for my departed friend and for another, far happier time. Urbino belonged to that privileged group of Portuguese—mostly continental—who worked in the mansions of that truly angelic neighborhood, a story that one day ought to be told in a book. Above all, I wish to stress that his work and his philosophy of life remained unshaken: a beautiful and incomparable record in the Portuguese language, which he handled—as Eduardo Mayone Dias once wrote in a long essay on his work—with finesse and agility, of our perpetual inner exile or, later, of exile on American soil.

A second book of “chronicles,” A América Segundo S. Lucas, contains a series of “letters” poised between reality and fiction, in dialogue with a “Filomena,” originally published in the aforementioned weekly Tribuna Portuguesa, then directed by the recently deceased João Brum. He also published, regarding our emigration to the Pacific coast, Os Portugueses na Califórnia, a historical and sociological essay on the lived experience and profane-religious ritual of the predominantly Azorean communities there.

He granted me an interview for Diário de Notícias in 1980, published under the title “The Emigrant Is a Shepherd with a Patchwork Cloak,” which later opened Plural Transitivo—a text I still quote frequently whenever immigrant or Luso-American literature is discussed. “It is the world,” he said, “standing on the bridge, indecision up to its hairline. It sways between the two banks, unable to relinquish the little Portuguese flag in its pocket, as they say in Onésimo’s theater, and the American skin it wears out of necessity, adaptation, and even recognition.” In those pages, Urbino not only defined himself in relation to his native country; he positioned himself fully as a writer of “immigration” or “exile,” call it what you will—naming colleagues, discussing their works, weighing our historical place in the United States, as well as what he hoped for and what disappointed him in April 25, especially after one of his less happy visits back to the land he had long since left but never forgotten, even within an American daily life utterly removed from what was happening on the other side of the great continent and the great ocean.

Portugal and our people were the lifelong breath of his conscience, his joy, and his sorrow. In Los Angeles—especially in the star-studded city of Beverly Hills—Urbino was the perfect stranger in a strange land. Never had the Portuguese language been more of a homeland than it was for him. He leaves behind a son, Marco, who grew up playing amid the supposed abundance of others and the true, lasting richness of his father.

Urbino de San-Payo, Plural Transitivo, Livraria Ler Editora, Lisbon, 1982. The author’s photograph was taken from the internet and is, I believe, among the most recent. His literary name was a semi-pseudonym for Urbino Manuel Sampaio Ferreira.

Vamberto Freitas at Seventy-Five

The Long Work of Critically Listening to and writing about Dispersed Voices

Filamentos – arts and letters

Bruma Publications | Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI),

California State University, Fresno

Introduction

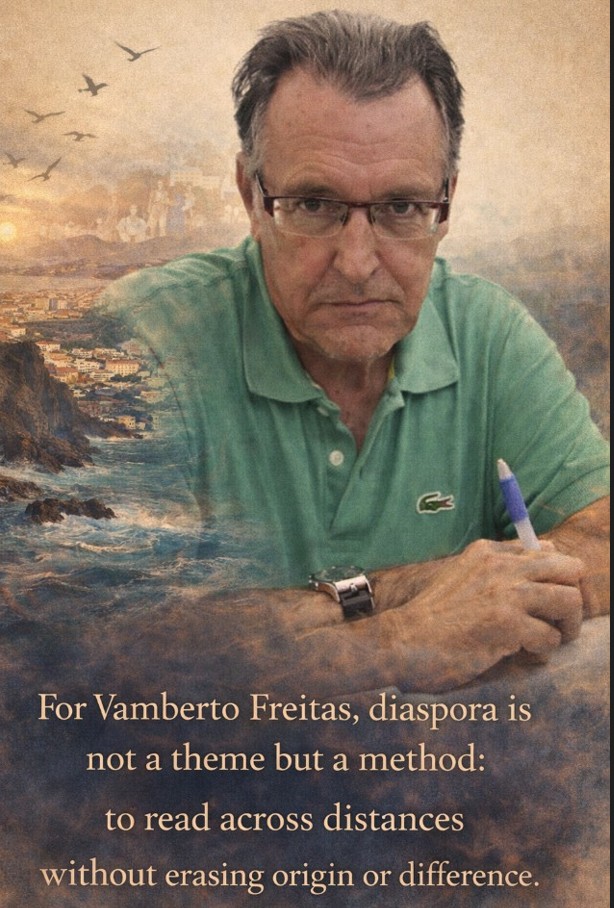

For more than three decades, Vamberto Freitas has practiced literary criticism as a form of sustained attention—patient, rigorous, and ethically alert. His work has traced the quiet, often overlooked trajectories of writers shaped by migration, insularity, and memory, especially those of American and Canadian authors with roots in the Azores. At seventy-five, his critical legacy stands not as a monument but as an ongoing conversation: a life of letters placed in the service of literature itself, where reading becomes an act of responsibility and criticism as a way of listening deeply to voices dispersed across geographies, languages, and generations.

Throughout the month of February, Filamentos – arts and letters, an initiative of Bruma Publications at the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI), California State University, Fresno, will honor this legacy with daily segments published from February 1 through February 28. Each entry will revisit, reflect upon, and extend the critical pathways opened by Vamberto Freitas, reaffirming the enduring relevance of his work within Atlantic, diasporic, and transnational literary studies.

Vision

To honor literary criticism as a form of cultural stewardship—one that listens across distance, preserves intellectual memory, and affirms the centrality of diasporic voices within the broader landscape of contemporary literature.

Mission

Through this February series, Filamentos – arts and letters seeks to celebrate the life and work of Vamberto Freitas by foregrounding criticism as a practice of care, rigor, and continuity. By publishing daily reflections, excerpts, and critical engagements, this initiative reaffirms Filamentos’ commitment to literature that crosses borders, sustains dialogue between islands and continents, and recognizes reading as an ethical act—one capable of holding dispersed voices in thoughtful, enduring relation.