Before we talk about the illustrations you created for Álamo’s books, I’d like to ask about this painting here with us. How did this portrait come into being?

It came about in the most Álamo-like way possible. The Biblioteca de Angra was organizing a celebration of his birthday—Álamo has many portraits; he was portrayed by several artists over the years—and he called me and said, “Look, they want to do an exhibition with my portraits, and I need a portrait by you.” And I said, “Alright.” That was how we communicated—simple, direct, informal.

And what was the idea behind this piece?

I think Álamo was expecting something more abstract, closer to my usual visual language. But I decided to surprise him, because I knew he also appreciated my drawing. I found this blue canvas—an industrial canvas, not even a traditional painting canvas, the kind used on boats and things like that, very durable—and I thought, “Álamo would look good on this.” I wanted to see what would happen if I worked from a blue background. There wasn’t any grand intellectual agenda behind it—just a desire to give his figure a certain mysticism and lightness, which really characterized the Álamo we all knew.

How did he react?

He loved it, and that made me very happy. This was during the pandemic, when everything was done by email and messages—COVID, lockdowns, all of that. I had more time then, which helped a lot. The first time he saw the portrait, I sent him a photo. I could tell immediately that he was deeply moved. He sent me a very emotional message, and that meant a great deal to me.

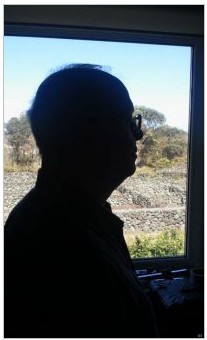

And the image used here in the library—the silhouette of Álamo—how did that come about?

That silhouette was created in my studio, against a window. One day Álamo came over and said, “They’re going to create a library with my name, and we need an image for it.” We started talking about what might work. He was a very creative person and often suggested ideas himself—he also drew, although later on he didn’t have much patience for it, and I would often execute things based on his sketches. This time he said, “Let’s try something like a Hitchcock silhouette.” I said, “Okay—stand in front of the window and let’s see what happens.”

Until the day he died, the original photo of that silhouette was the image that appeared on my phone whenever he called me. Later it was used here in the library, and I also ended up using it in a translation of his poetry by Diniz Borges. It’s been reused many times since. Everything always grew out of informality. I had known him since I was very young, so things were easy between us.

Your collaboration with Álamo extended into many areas, including theater set design. Was he influential in your decision to pursue the visual arts?

Very much so. He was one of my greatest influences. I was lucky to have a family that never pressured me. Maybe they realized early on that I wasn’t good at anything else. But they never said, “Don’t do that—you’ll never make money, you’ll have a miserable life.” They said, “Go for it. You’ll have to work, but if that’s what you love, there’s no point in doing something else.”

Álamo was one of the people who pushed me the most. He started writing about my work very early on, which helped immensely. Sometimes I think people knew my work more through Álamo’s texts than through the work itself. Because I trusted him, I was always inviting him over. Those invitations were vaguely self-interested, I’ll admit. But he always came, with his kindness and generosity—he really was an extremely generous person. He could have said, “I don’t have the patience to put up with you anymore,” because I was persistent. But he genuinely loved the visual arts. And he himself was a visual artist.

What did that support mean to you personally?

It moves me deeply, even today, to think about the interest he always showed in my work. That’s something I carry with me. I wouldn’t be the artist I am today without his encouragement. But it was never a controlling influence.

It was more about being present?

Exactly—about being there. And about doing something fundamental for artists: writing about their work. Without writing, it’s very hard to build any kind of history. This may sound like vanity, but it isn’t. It’s essential. Even today, in major art markets, there are established circuits—sometimes a bit perverse—where if you fall into the right graces, your career is made. There’s a whole machine behind it.

That was never the case with Álamo Oliveira and me. Ours was something naïve, in the best sense of the word. He wrote because he believed in the work, and because he had access to the media.

He used to coordinate a supplement in Diário Insular…

Exactly. That supplement was vital to Terceira’s cultural life, and I think it was a real shame that it came to an end. But these things end up being overtaken by other priorities beyond our control.

And your collaboration continued through the reissue of Álamo’s complete literary works, published by Companhia das Ilhas…

The illustration of the covers for all those books was a very extensive undertaking. It’s work I’m very proud of. But to be completely honest, it was actually some of the easiest work I did with him.

Because, as it happened, in those conversations we had, he said to me, “I’ve got a problem. They’re about to publish all my books, and I’m going to need lots of covers. And you’re the one who’s going to do them.” And I started thinking: if I had to create everything from scratch, it would be deep, time-consuming work—there were still many volumes.

I knew he was interested in my painting, so I made him a proposal: “Álamo, what do you think if we use paintings for each of your books? You can go to my website or my studio and choose—‘I want this one for this book, and that one for that book.’”

Paintings that were already produced…

Yes. There was only one exception, which involved a photomontage he asked me to create (the book of American short stories, if I’m not mistaken). There had to be a kind of silhouette of an American flag, but it was over one of my own photographs—a photograph with a slightly painterly quality.

That was how the work went. And all the actual work involved was cropping the image to the size the printer required and sending it properly prepared, with the correct specifications. So it wasn’t one of the more labor-intensive projects for me, but it gave me great pleasure to do it.

(To be concluded next week.)–From Diário Insular, José Lourenço, director.

These conversations are conducted in the Álamo Oliveira Library in the Civil Parish of Raminho by Andreia Fernandes, a writer and journalist

Translated by Diniz Borges