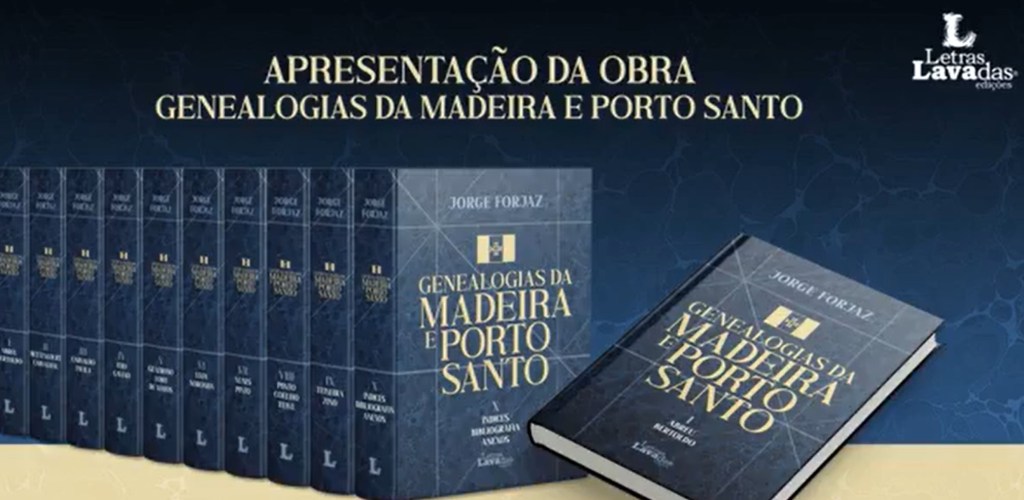

As he nears the end of a project born almost by accident—the genealogies of the former Portuguese Empire—Jorge Forjaz is preparing to present, on the 15th of this month in Angra do Heroísmo, the genealogies of Madeira and Porto Santo. Across the old Portuguese world, he discovered lives in constant motion—journeys that might begin in Lisbon and end in Cape Verde after passing through half the Lusophone globe. As he pauses, he says, the genealogist is already preparing the genealogies of Angola, bringing the imperial cycle to a close.

You’re presenting the genealogies of Madeira and Porto Santo, the result of extensive research. What stood out most?

In this work—as in all the genealogies I’ve studied—the most interesting aspect is the object itself: handling information that, whether abundant or scarce, allows us to trace the chain linking generations. In some places documentation is limited, and the genealogical result can be frustrating, though no less labor-intensive. In others, the outcome is fascinating thanks to the quality of the sources—Madeira being a prime example. The researcher there has access to a magnificent archive, an extraordinary collection, and an exemplary cataloging system. Working in the new Madeira Archive and Library is a pleasure—truly world-class anywhere in the Portuguese-speaking world, which I know well.

When you analyze family connections, what mixtures stand out? Where did the peoples of the two islands come from? Are tourism flows leaving visible marks on families today?

When we speak of islands—by which I mean the Azores and Madeira—we must remember that this was not colonization but settlement. There was no one here. Those who first arrived can be labeled the founding fathers of these Atlantic societies. We don’t know the exact day or even the year they landed, how many they were, or all their names—but we can be certain that among them are ancestors of every Madeiran drawn in the genealogical lottery.

As in the Azores, most settlers were Portuguese. But there were also Flemings, whose presence forged important ties with Flanders and trade networks that exported sugar while importing works of art—especially painting—now considered the most significant collection of Flemish art in Macaronesia (just visit the Museum of Sacred Art in Funchal). Still, Flemish settlement in Madeira was far less extensive than in the Azores, particularly the Faial/Pico/Flores triangle.

Few Madeiran surnames are of Flemish origin, but among them is Jan Esmenaut—later transformed into João Esmeraldo—founder of one of Madeira’s most powerful houses, lords of Lombada dos Esmerados, the island’s largest landowners, with properties across all municipalities. That line culminates in the famous Count of Carvalhal (D. João do Carvalhal Esmeraldo), whose mismanagement left him nearly destitute, selling off estates—including the famed “Terras do Conde” in Graciosa—along with silver, porcelain, and a magnificent set of heraldic harnesses now housed in the Museum of Angra.

There were also Italians—Spínola, Acciaioli, Perestrelo (Pallestreli), Lomelino (Lomelini, which also gave rise to the Melim), Bianchi, Passalaqua (maternal grandparents of Admiral Gouveia e Melo); French (Bettencourt, Sabois de la Tuellière, Sauvaire); English (Drummond, Welsh, Zino, Blandy, Wilbraham, Hinton, Cossart, Leacock, Magrath, Sarsfield, Reynolds, Phelps); Germans (Spranger); Spaniards (Herédia, Valdavesso), among others. Over time, these families intermarried with earlier settlers, so that today, regardless of lineage, every Madeiran carries a bit of all this in their DNA.

And when I say “many ancestors,” I mean it literally. No one is born of nothing: we all have two parents, four grandparents, and so on, doubling each generation. After twenty generations—enough to reach Madeira’s settlement—each Madeiran has more than one million ancestors: precisely 1,048,576 (2²⁰).

Madeira’s rugged geography—steep mountains, long valleys, narrow fajãs—and a historically weak road system meant the sea mattered more than roads. Many communities lived in near-closed circuits, often marrying cousins within the same parish. That pattern has faded over recent decades and largely disappeared with modern roads, bridges, and tunnels that turned a once multi-isolated territory into a single global village, dissolving centuries of intense endogamy.

Your work on the former Empire’s genealogies seems to be moving quickly. Are there clear trends—population movements, crossings—that stand out?

First, a clarification: there was never a formal project called “the genealogies of the former Empire.” No sane person would sit down and plan something stretching from Corvo to Timor. Like all genealogists, I had my areas of preference—mine were the Azores, especially Terceira. I might have stayed there, perhaps adding Graciosa or São Jorge, which others are studying.

But fate—perhaps luck rather than misfortune—took me to Macau. To fill my time, I began research that, eight years later, became three massive volumes of over 1,000 pages each. From there came Goa, capital of the Eastern Empire; then Mozambique; São Tomé and Príncipe; parts of Cape Verde and Guinea; Angola (now in preparation); and the North African outposts of Ceuta and Tangier. I also followed Brazilian families—Monjardinos, Stocklers, Forjaz, Dart, Teixeiras de Sampaio—many with deep imperial roots. It was a “since I’m here” strategy that let me traverse territories, archives, and families as few Portuguese genealogists ever have.

One thing stands out: the Portuguese were true wayfarers. Born in Lisbon, married in Macau, two children in India, four years on Mozambique Island, a transfer to Bissau, and death in Cape Verde. Everywhere, they left a footprint. Mapping that footprint is what I did—now a collection of more than thirty volumes. It couldn’t have been planned. It just happened.

Did you find Azorean connections in this new work and across your imperial genealogies?

Look at the Atlantic islands arranged vertically: the Canaries below (truly colonized, with the Guanches resisting Spanish rule), then Madeira, and farther north, the Azores—discovered in that order. Take the Bettencourts: from Normandy to the Canaries, then Madeira, then the Azores, and from there to Brazil and Spanish America. Today, it may be the most Atlantic of surnames—found in Tenerife, Câmara de Lobos, Ponta Delgada, Velas, Rio Grande do Sul, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Havana—with dozens of spellings cataloged by a Canaries scholar. Curiously, in Madeira and the Azores the original spelling endures.

Or consider the Ornelas brothers, Álvaro and João: the first ancestor of all Ornelas in Madeira, the second of all Ornelas on Terceira. Their tombs—one in Funchal Cathedral, the other in the parish church of Praia da Vitória—are beautifully preserved, a rare case in the Portuguese world of two brothers born in the 15th century and buried little more than a year apart.

What comes next? Will you continue with imperial genealogies?

Now—rest. I began Madeira exactly five years ago: more than 1,800 days without vacations, weekends, or pauses. I knew the scale of what I’d undertaken—Madeira and Porto Santo together have a larger population than all the Azores—and without pressure, I’m not sure I’d have finished. The frenzy turned out to be a good adviser. The result is here; I hope it meets its readers well.

To answer your question: I’ll shift into cruising speed on a small Angola project, to preserve what I gathered during a less-than-fruitful visit. With that, I’ll definitively close the genealogies of the Empire. Timor will remain outside—essential documentation was destroyed during the Indonesian occupation. That was a devastating footprint indeed: instead of aiding the genealogist, it sealed the archives and plunged a society into ignorance of its own past.

In Diário Insular–Photos from Diário Insular, Letras lavadas and Biblioteca Publica de Angra do Heroísmo.