Translating Island and Return was, for me, less an exercise in moving between languages than an act of listening. A slow, patient, almost ritual listening—like approaching the sea not to describe it, but to learn its cadence. There are books one carries across; this one required a crossing. And there are poets who write about the ocean; Aquiles García Brito writes from within it.

This book is born—as I note in the preface—“from the edge of the world, where the sea is not scenery but method, and the island is not a place but a condition of being.” Everything in Island and Return organizes itself around that radical conviction: that language is a form of water, and that writing is an acceptance of the wave’s cyclical motion—advancing only to return, changed.

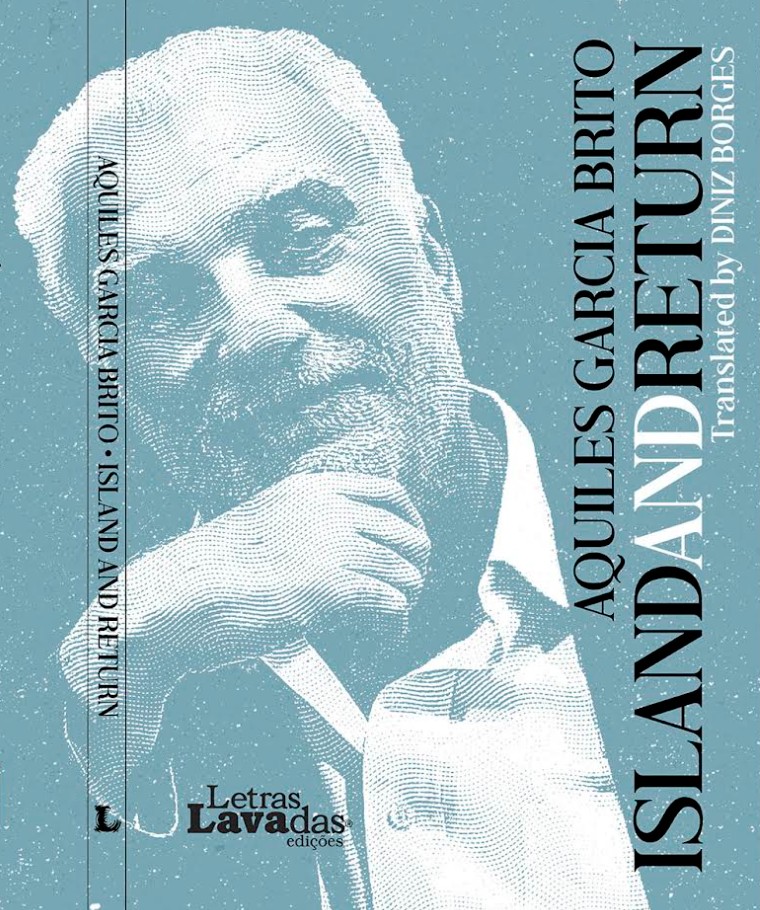

Aquiles García Brito belongs to that rare Atlantic lineage for whom the sea is not an ornamental metaphor but an epistemology. His poems think the way the sea thinks: circularly, by backwash, by erosion and reappearance. Nothing here is fixed; everything settles only briefly. The word does not conquer—it drifts. It does not possess—it listens. It does not close—it returns.

As I translated these poems, I came to understand that the true challenge was not lexical but respiratory. Each line asks for space, for silence, for interval. Each poem is an act of navigation, in which words are fragile vessels and silence is the compass. As the poet himself writes, “everything returns—circular, undulant—for there is no other recourse.” To translate, here, was to accept that continuous return—without nostalgia, without the illusion of arrival.

The back cover rightly notes that Island and Return “inhabits the space between departure and return, tracing fragile cartographies of voice, memory, and belonging.” That fragility is not weakness; it is an ethic. Aquiles García Brito writes against the temptation of possession, against the excess of the shout, against the sovereignty of the self. His poetry practices a discipline of attention—a form of ontological humility that is rare in our time.

The poems move between the mythic and the everyday: an empty suitcase, a street, a west-facing house, an airport, a shared soup. Yet in each minimal gesture the infinite pulses. The ordinary radiates ontological density—like a wave which, though nothing but water, contains the rhythm of the world.

If the island is the book’s symbolic place, return is its philosophy—not as paralyzing nostalgia, but as renewal. Return here is not geographic; it is ethical. It is the awareness that every departure carries a principle of home, and that every true home is transient. For this reason, the book does not build monuments; it builds passages.

I want, at this moment, to congratulate Aquiles García Brito on this work of luminous maturity—on a poetry that does not seek to dominate the world but to inhabit it with care. Island and Return gives us back what is essential: rhythm, listening, the awareness that to exist is to be in dialogue—with the sea, with language, with others.

I also wish to thank the Azores Commissioner, my friend José Andrade, publicly, for the generosity of reading this text. His reading is an act of friendship and shared attention—a way of being with poetry not as ceremony but as lived experience. To read, here, is to recognize landscapes that precede us and bind us, in a complicit silence where the word finds its true rhythm.

To all those present, and to the readers yet to come, I send my enduring embrace, with deep esteem. May this book find you between the water that shapes us, the voice that calls us, and the return that transforms us—not as a final answer, but as continuous movement; not as a harbor, but as a crossing. May Island and Return remain thus: water that writes, voice that listens, return that never concludes. For it is in that circle—always returning—that poetry breathes and gives us back, again and again, to all that is still writing us.

Diniz Borges