Stories of how island memory took root in Valley soil—and grew into who we are, and who we are still becoming.

Hydrangea Tide: An Immigrant Grammar of Work, Prayer, and Return

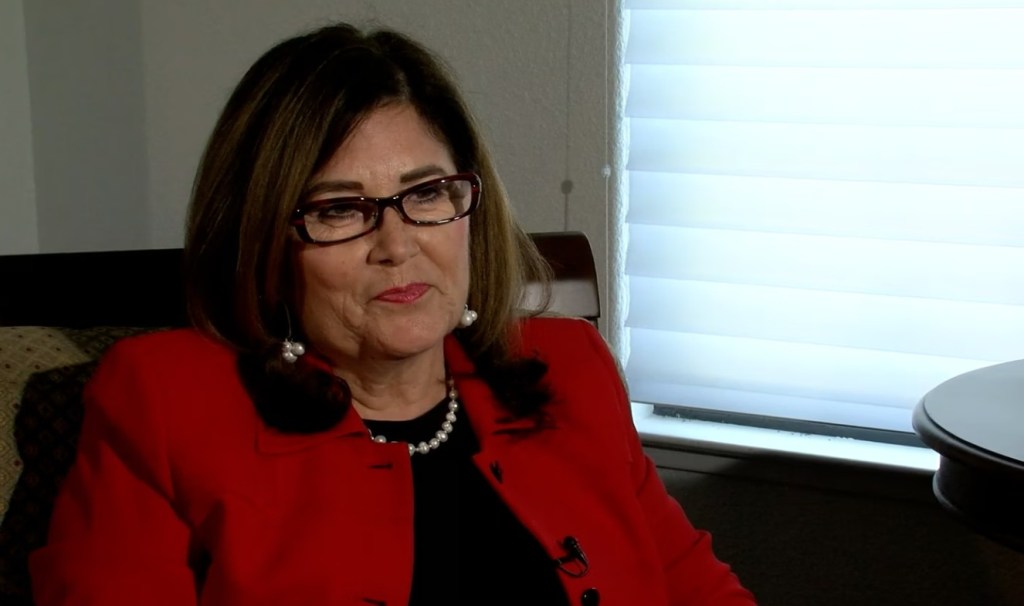

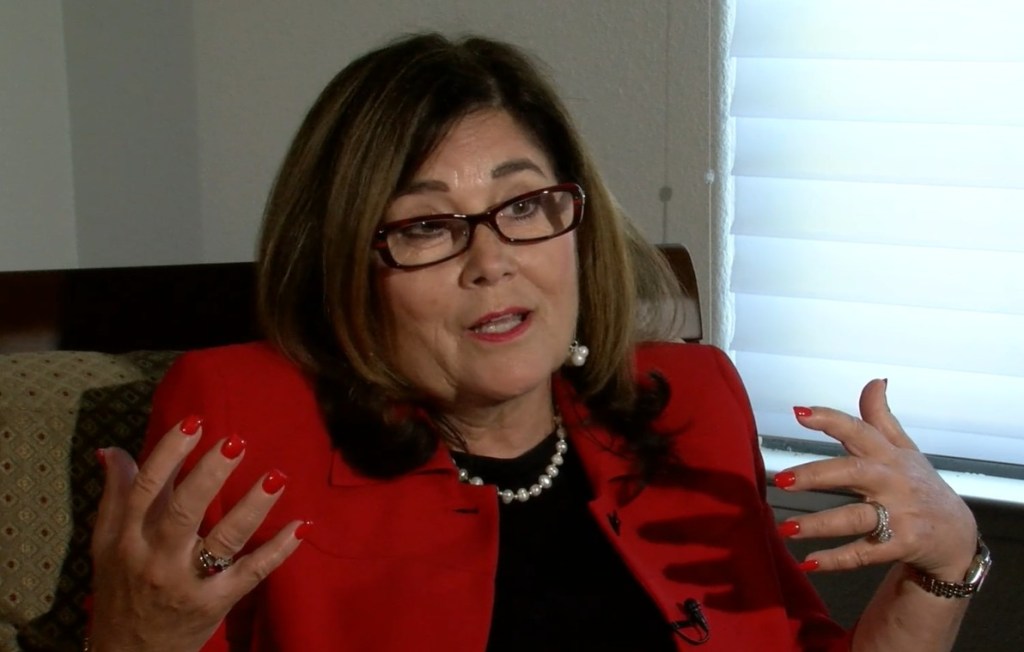

Some names are not merely names; they are heirlooms pinned to the chest, small invisible crowns that tether a life to a place of wind and salt. Maria Hortênsia Silveira begins there, as if opening an old window and letting in the scent of hydrangeas—the Azorean emblem in bloom, blue as a weathered sky, abundant as if the earth had learned to translate the heavens. To be named for a flower is to be given, from the start, a vocation: to keep flowering even when the root is moved.

She was born in Piedade, on the island of Pico, and even geography feels like a parable: a small village under a volcanic shadow, where the Atlantic keeps time, and the hills teach endurance. Her birthday is May 1st, spring entering the body like a promise. Then comes the crossing. 1967: a year that, for so many Azorean families, is not just a date but a rupture in the map—the moment life widens into immensity, and immensity becomes another word for fear. Maria Hortênsia was fifteen, and she came with her father, her mother, and her younger brother: four people and a kind of improvised faith.

What did they bring? Almost nothing. One suitcase that wasn’t even full. A pair of shoes on each body. A few changes of clothes. A bit of money. Tickets bought with borrowed dollars. Exile, sometimes, fits in a small space—not because it is light, but because the rest is left behind: friends, familiar streets, the rhythm of one’s language, the saints that guard a childhood, the simple mercy of recognizing the world.

And yet her story bends the usual arc. She says, with a laugh you can almost hear through the transcript, that she was “the culprit.” Their emigration begins not so much out of necessity but of desire—an almost quixotic hunger for languages. At seven, she was learning French; by thirteen, she had declared she wanted to go to France, to live inside the music of another tongue. France never arrived. But the desire did not vanish—it rerouted, as destiny often does, into America: the great translation.

The entrance, however, was not triumphant. They landed in Boston, then flew on to San Francisco, and in one of those unglamorous intervals where a life quietly decides what it will become, they waited at the airport until morning—because her aunt didn’t drive and her aunt’s older husband couldn’t either. Immigration is made of these details: the long night under fluorescent light, fatigue like a second skin, the clock refusing to match the heart. At last, they took the bus to Turlock, arriving on Good Friday—which feels almost too perfect, as if the American story demanded first a rite of loss before granting anything like resurrection.

That first night in a modest home—dirt road out front, so far from the Azorean myth of America as heaven, where money “falls from the trees”—Maria Hortênsia went upstairs, looked out the window, and began to cry. Not only from homesickness, but from fear. The fear of not knowing. “I didn’t know a street,” she says. “I didn’t recognize anyone.” Exile is a world suddenly without captions. And then her mother comes, as mothers do in the mythology of migration, and offers the sentence that holds families together like a beam: Everything is going to be okay. Not a prophecy—more like a survival technique.

The next day brings a second shock, almost comic, almost theological. Raised in the formal Catholic cadence of the Azores, Maria Hortênsia is taken to a Born-Again church: guitars, singing, bodies falling to the floor, voices rising, a kind of spiritual weather. She’s terrified—and then she laughs. Between fear and laughter, a defining capacity appears: the ability to pass through strangeness without breaking. Her aunt supplies a pragmatic ecumenism that sounds like folk philosophy: It’s a different religion, but it doesn’t matter—as long as you’re praying to the same God. In a few plain words, diaspora revises the sacred: less form, more essence; less institution, more human need for meaning.

But if church startled her, school was the true abyss. In the Azores, Maria had been the top student in her class. In America, she couldn’t understand the teacher, couldn’t read the books, couldn’t hear herself in the language. Every day she walked home repeating a private litany: I convinced my parents to come here—now I have to convince them to go back. And her mother answered with the kind of soothing postponement that has saved countless immigrant households: We’ll stay six months, a year—then we’ll return. The imagined return as anesthesia, until the body learns to live.

And Maria Hortênsia learns—through a door the world did not expect. Languages have become her bridge. In French, where she could speak better than the teacher, she finds not only competence but dignity: a place where she is not diminished by her accent. In Spanish, she discovers the ease of Latin roots, the underground kinship between tongues, the secret geography of words. Languages give her friends; friends return the world to her. English, slowly, ceases to be an enemy and becomes a tool.

Here, the Portuguese community arrives like a second shoreline. Turlock had a strong Portuguese presence, and with it, Maria Hortênsia finds “the real Catholic church,” even a Portuguese priest. She joins the choir. She starts a youth group. She goes to Portuguese festas and says a sentence that could summarize the immigrant metamorphosis: Life began to feel fun again. The festa is not a folkloric ornament—it is a belonging made audible. It is where exile stops being only a wound and becomes, also, fabric.

Meanwhile, the family climbs the American hill by pure labor. Her father begins milking cows—work he had never done back home. Her mother hears about fruit-picking, and soon all four are rising at four in the morning, before school, to harvest what California offers—not as a miracle, but as a requirement. Then her father hears about Foster Farms, a place where you don’t have to wake up at midnight for the dairy, and he works there for twenty years, retiring at sixty-two. With steadier wages, weekends return; the “fun part” of life—church, community, festas—becomes possible again. America, in this family’s story, is not a sudden blessing. It is rhythm. It is a machine that yields ease only when you learn its mechanism.

And then the narrative turns, as good narratives do, on a single moment that becomes an internal myth. Maria, who dreamed of becoming a professor—Master’s, PhD, the large school, the long corridor of academia—takes a job at Foster Farms because it pays better than the nursing home. There are union tensions, elections, and conflict. They call her because she speaks languages. She goes in thinking she is only translating words—and discovers something deeper: people complaining, hurting, asking questions, and no one present to listen and answer. That moment is the birth of her vocation: translation not as grammar, but as justice.

When Paul Foster calls her into his office—she’s only eighteen—he tells her that the union leaders said, “If it wasn’t for that little Portuguese girl, we would have won.” And then he gives her a sentence that becomes a kind of talisman against every future wall: If you were able to do so much in such a short period of time, there’s a hell of a lot more you can do. Maria keeps those words the way some people keep prayers. Whenever she meets a brick wall, she thinks of that sentence and finds a way to the other side.

She changes course: from languages to management, then to business administration, to human resources and labor relations. Not because she abandons her love of language, but because she decides she wants to be where meaning has immediate consequences, “where the action is.” She will teach at night for a while, yes, but she chooses the center of the current.

What makes her rise more than an American success story—the kind that often polishes away the cost—is that she never forgets the body. She began on the line. In the Ice Pack department. Hanging chickens, production moving at 112 birds a minute, her hands performing a relentless liturgy: place the small logo on the wing, repeatedly, sixty-one per minute. “Golden Guarantee.” Two chickens are free if the customer is unhappy. Capitalism speaking in promises. Yet what she carries forward is not the slogan—it is the ache: the hand, the back, the arm. Later, when employees sit across from her and describe pain, she understands it not as theory but as muscle memory. Her authority is built on the fact that she has been one of them.

Decades later, she becomes Vice President of Human Resources and Labor Relations, responsible for thousands of workers across multiple states—plants, ranches, hatcheries, feed mills, truck shops, distribution centers; contracts, negotiations, the long choreography of labor and peace. She is proud of what sounds almost epic in its rarity: never having a strike under her negotiations. A perfect record, she calls it, crediting her staff. That pride is not mere corporate accomplishment; it is an ethic: the belief that conflict can be held without rupture, that people can be heard before they must explode.

And through all of this—the climb, the work, the responsibility—she keeps her allegiance to origin in living form. She goes back to the Azores every year. She loves Portugal and the islands with a devotion that is not sentimental but bodily: the blue water, the clean air, the green hills, the birds, the fish. She speaks of building the Adega—a kind of winery and wine tasting, a place of cultivation—as if to say: the immigrant story does not only leave; it also returns to plant.

Her most revealing metaphor arrives almost casually: Portugal is her biological mother; America is her stepmother—the one that opened her arms and treated her as its own. It’s a metaphor both tender and unsparing. She does not romanticize exile. She names it as adoption. And still she honors the stepmother’s generosity: “Only in America can this happen,” she says, with the awe of someone who has watched the improbable become real.

At home in the U.S., she keeps the old practices not as relics but as daily architecture: she still prays in Portuguese; she cooks Portuguese food; she goes to festas; she listens to Portuguese music, especially fado, which she translates, beautifully and accurately, as “destiny.” In her car, the radio is set to 1330, KLBS, as if the frequency were an umbilical cord: the community voice keeping the language from dissolving into noise.

She tells a story about an earlier radio program—“Franklin Speaking”—and how she once judged the host’s Portuguese not good enough for the airwaves. Later, she learns the deeper lesson: no matter how many years you live here, if you don’t guard the language, it fades. She listened to the imperfections and decided to keep her Portuguese sharp. Sometimes, it is a flaw that saves you. Sometimes, it is hearing the language stumble that teaches you to hold it.

When asked what it means to be Portuguese-American, she doesn’t answer with flags. She answers with ethics. It means, she says, you must make a difference. You are here for a purpose. You must leave a legacy. Not how much money you made, but how good a daughter you were, how good a sister, an aunt, a wife, a friend, a good person. She describes a lifelong instinct to help: the grandmother, the teacher, the neighbor. She learned it in the Azores, saw it in her mother, her father, her aunts, and carried it into America as continuity, not nostalgia.

And that is the real poem embedded in her interview: a life built as a translation. Fear translated into laughter. Homesickness translated into work. Language translated into belonging. The assembly line translated into empathy. Negotiation translated into peace. A girl named Hortênsia—hydrangea—crossing an ocean and proving that flowering is not the denial of origin but its continuation, carried like perfume into the future.

There are lives that rise like ladders.

And there are lives that rise like hymns—step by step, repeating what saves: a language, a prayer, a table, a hand extended—until America, at last, is no longer the place of fear, but the place she chose to remain.

Diniz Borges

You can listen to the entire interview on our library archive or on Youtube

https://omeka.library.fresnostate.edu/s/portuguese-beyond-borders-institute/item/267

Maria Hortênsia Silveira was also part of our first documentary: Untold Stories.