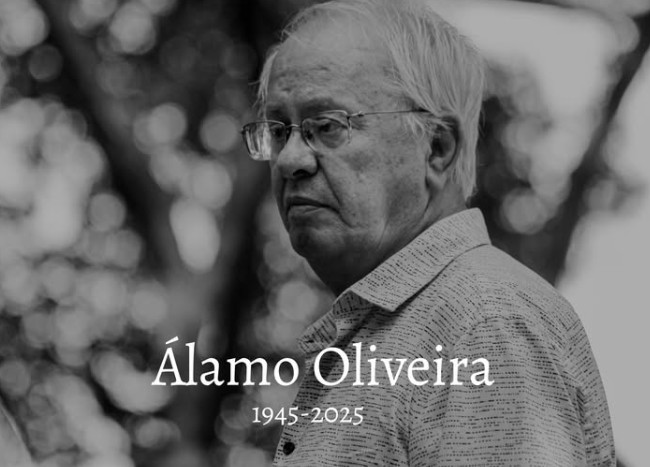

Álamo Oliveira, Raminho, and the Ethics of Writing from Elsewhere

Opening —

To write from an island is not, in itself, to be enclosed by it. In Álamo Oliveira’s case, Raminho—the civil parish from which his voice first emerged—was never a limit, but a discipline: a way of attending closely to the world before daring to speak of it. From this peripheral place, within an island already peripheral to the dominant circuits of Portuguese letters, Álamo Oliveira shaped a body of work that resists confinement while remaining rooted.

His writing does not abandon the parish; it carries it. The cadence of conversation, the intelligence of walking paths, the coexistence of rural and urban worlds, of learned and experiential knowledge—these are not background details but ethical coordinates. They remind us that literature is not produced by scale or centrality, but by attention. In Álamo Oliveira, the local becomes legible without becoming provincial, and the island opens outward without dissolving into abstraction.

This conversation, held at the Álamo Library in Raminho, is therefore more than remembrance. It is a re-situating of a writer whose work belongs to a geography of circulation rather than isolation. In listening again—to his books, to those who knew him, to the place that formed him—we are reminded of a principle Filamentos holds at its core: that insularity, when practiced with rigor and imagination, can become a mode of ethical openness.

We thank Diário Insular, writer Andreia Fernandes, the Raminho Civil Parish Council, and Photographer António Araújo for their collaboration. Aálmo would love to have these conversations reach the Azorean Diaspora.

A series of interviews promoted by the Raminho Parish Council, with the support of the Angra do Heroísmo City Council, to honor the late writer Álamo Oliveira—himself a native of the parish—began on December 27, 2025, at the Álamo Library. The opening conversation featured Professor Álamo Meneses, former mayor of Angra do Heroísmo, interviewed by journalist Andreia Fernandes. Our newspaper (Diário Insular) joins this initiative by publishing selected excerpts from these conversations. The selection is curated by Andreia Fernandes.

The first guest in this cycle of conversations at the Álamo Library bears the same name as the honoree: Álamo Oliveira. José Gabriel do Álamo de Meneses—does this shared name signify a connection?

Yes. I am usually known simply as Álamo, just like the honoree, which has occasionally led to some confusion.

There is no close family relationship. However, the name Álamo is extremely rare in the Azores. I only know of Álamo(s) originating from these parishes along the west and northwest coast of Terceira. So, at some deeper level, there must be a connection, though not a direct or close one.

What kind of relationship existed between the two Álamos?

There was a considerable age difference between us. I met Álamo—the real one, as I sometimes say—when I was still quite young. I grew up in Altares. Officially, I am from Praia da Vitória, but in reality, my family and I have always lived in Altares. A hospital accident, combined with a law that required people to be registered not where they lived but where they were born, made me from Praia da Vitória. But I never lived there.

I first met him during church festivities in Altares. He was often involved in organizing events—choirs, theater, cultural activities—very much in his role as a man of all the arts. Whenever creative support was needed, he would appear. That is where our paths first crossed.

Over the years, we remained in contact, but our relationship grew closer during my time as mayor, when the process of publishing his complete works was underway. From that point on, our contact became much more frequent and more personal.

A connection that lasted until his final days… You even helped him return home from Braga, where he was staying with a niece while receiving medical care.

Unfortunately, that episode was not a pleasant one—but such things happen.

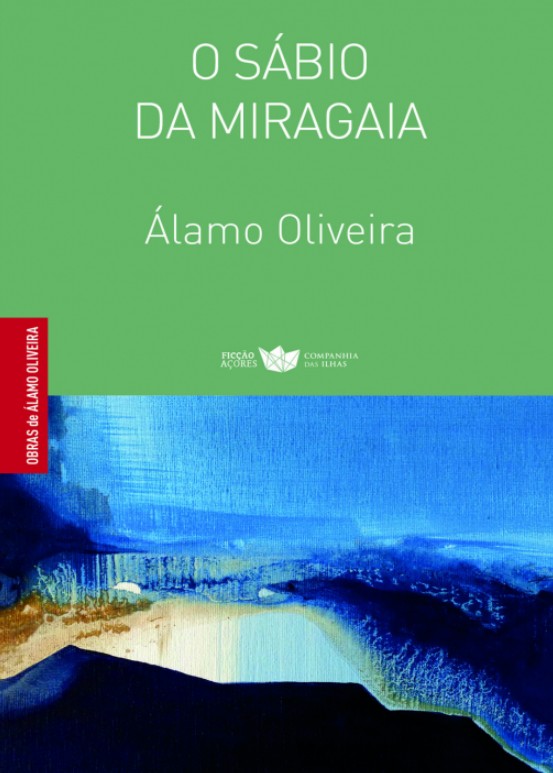

We asked you to choose a book by Álamo Oliveira to bring with you today. You selected O Sábio da Miragaia. Why this book?

I chose this book for two main reasons. First, because it is one of his most recent works, dated by the author as 2020, the year of the pandemic. Second, because within the context of Álamo Oliveira’s oeuvre, it possesses two particularly interesting characteristics.

The first is that it is unmistakably a work of maturity. What we encounter here is a book deeply informed by the tradition of Platonic dialogues—Timaeus, Critias, those classical texts—yet reimagined. In this case, we are given a “dialogue” that is not truly a dialogue at all, but rather a monologue. It is the voice of an old man speaking to a younger man, who never responds. Through this one-sided conversation, life experience is transmitted, reflected upon, distilled.

This is fascinating because we come to understand Álamo himself through these pages. Those who knew him—and those who know Raminho and the island of Terceira—recognize the setting, the cadence, the worldview.

Running parallel to this is another narrative thread: an unlikely friendship for its time—likely set before April 25, in the 1960s or 1970s—between an urban lawyer from Angra and a man from a parish, a farmer named Cristiano. Their relationship evokes a world many of us older readers still remember: an island marked by a strong dichotomy between the urban center and the rural hills. Yet here, these two worlds enter into a kind of symbiosis, each contributing its knowledge, its experience, its way of understanding life.

And then there is the title itself.

Those who know the island immediately think of José Agostinho, the wise man who lived in Miragaia. But in fact, the book is not about him—although at first it seems it might be. Instead, the “sage of Miragaia” turns out to be the lawyer: a man of humble origins who acquires experience and knowledge in the city.

Thus, the book unfolds along two intertwined paths. One is what the author calls the “conversation on foot”: the old man speaking to a silent younger listener. The other is the story of the friendship between the urban and the rural, between academic knowledge—the lawyer educated in Coimbra, a man of formal learning—and the farmer, who could barely read or write, yet possessed other forms of wisdom, other kinds of study.

Through a twist of fate, these two become confidants. Their exchanges place side by side different kinds of knowledge, different experiences of the world. The book alternates between these conversations and the unfolding history of their relationship, which is also the story of two worlds learning to listen to one another.

Another great strength of the book is its immediacy. As we read it, we recognize our own universe. We recognize the trails, the paths—it even mentions the ostriches of Santa Bárbara.

It is a profoundly local book, and yet one that addresses an extraordinary range of themes—particularly in those conversations—that are unmistakably universal. Someone reading it on the other side of the world will still find it compelling, because it speaks to what is human: feelings, ways of thinking, life events that can occur in Raminho just as easily as anywhere else. People are people. At its core, the book is about human experience.

That is why it is such a rich and rewarding work: it invites both a local and a universal reading.

I know that few people have read it, largely because it was published in collaboration with the City Council and had a limited print run. That is why I strongly recommend it. This is Álamo Oliveira at the height of his maturity, and it is a book with multiple layers of meaning—one that rewards attentive reading and lingers in the mind. It is one of those books that, once begun, carries you steadily to its final page.

It is the local universality of Álamo…

Exactly. It is what we might call the glocal: the global and the local coexisting. The stories are rooted in a specific place and time, yet they resonate beyond them. Readers elsewhere may not recognize the references, but they will feel the texture, the humanity, the depth those details bring.

Is this the dimension in which we should remember Álamo Oliveira?

I believe so. Álamo Oliveira should be remembered as a man who, from Raminho—a place peripheral within the island, peripheral in global terms, and particularly peripheral within Portuguese-language literary production—managed to create a body of work of genuine universal value.

That is our responsibility today. Initiatives like these events are a meaningful contribution. We must help break the isolation that surrounds his work—an isolation imposed not by its quality, which is unquestionable, but by the circumstances of place and publication.

The edition co-financed by the City Council, including this volume, significantly improved the graphic presentation of his books, with covers by Rui Melo. Most of his earlier works were self-published, with varying formats and visual identities, some of which were not especially appealing to a broader audience. Important steps were taken, but the decisive one has yet to be made.

Because the truth is that this work deserves far wider circulation, at least among Portuguese speakers. It stands shoulder to shoulder with much of the best literature produced and sold nationally.

At the same time, we are living in a difficult moment for books. We inhabit a hybrid era: books still exist, but so do Wikipedias, digital editions, and endless streams of information. More people are reading than ever before—but they are reading screens, fragments, brief messages, not necessarily books like these.

There is work to be done. And I hope that the Parish Council, the parish itself, and the Region—because this should be a collective responsibility—will have the strength and commitment required to carry it forward.

Filamentos Thanks Diário Insular, the Raminho Civil parish Council, writer Andreia Fenrandes, and Photographer António Araújo for their collaboration.

Closing —

Remembering Álamo Oliveira today is not an act of sentiment, but of responsibility. His work asks to be read beyond Raminho and beyond Terceira—not because it outgrows its origins, but because it fulfills them. What emerges from his writing is not folklore, but thought; not enclosure, but relation. His pages are inhabited by crossings: between countryside and city, silence and speech, memory and inquiry.

More than any other writer of his generation, Álamo Oliveira was also a writer of the diaspora—not simply because his work traveled, but because it understood displacement as a defining condition of modern life. His characters and voices move between worlds, carrying the island with them as memory, ethical measure, and unfinished question. In this sense, his writing anticipates readers who live elsewhere, who belong to more than one place, and who recognize the island not as nostalgia, but as a way of thinking.

Raminho remains present in his work not as a fixed point, but as a moral origin—a place from which writing learns how to speak outward without erasing itself. This is the ethics of writing from elsewhere: to remain accountable to where one comes from while refusing the isolation that geography can impose.

In this space between island and horizon, Álamo Oliveira’s voice continues to circulate. And in reading him now, we affirm what Filamentos exists to practice: that culture does not survive by standing still, but by learning how to travel—attentive, responsible, and open to the world.