Attempts to rewrite history are not a recent phenomenon, nor do they arise solely from the limitless possibilities of artificial intelligence or the viral replication of unsubstantiated opinions on social media.

Cinema, television and, even earlier, the written press have long been platforms for constructing narratives that—though anchored in real events—do not always correspond to factual truth.

I recently finished reading The Secret Language of Cinema, by Jean-Claude Carrière, the renowned French screenwriter and cinephile. The book—which I will discuss in greater detail elsewhere—proved enriching, not merely because of Carrière’s mastery of cinematic “language,” but also because he writes from within the industry itself. While his insights do not break entirely new ground, they allowed me to sharpen an intuition I had already formed—and which I now share with the readers of Sala de Espera: cinema frequently rewrites, simplifies, sanitizes, or romanticizes events and social processes that were anything but unblemished. Certain production companies have even specialized in this subtle art of narrative persuasion, crafting epic retellings of conflicts, erasing contradictions, transforming defeats into moral victories, and converting colonial tragedies into redemptive adventures.

The placement of the camera, the hero it chooses, the enemy it constructs—all of these decisions serve not merely to guarantee box-office success. They disseminate a vision of the world that often stands far removed from historical reality. Hollywood offers numerous examples of this—indeed, more than enough.

As you will have already concluded, none of this is new, nor does it constitute a startling discovery. Readers of this column understand it intuitively, even if, like me, they possess neither practical experience nor deep technical knowledge of the seventh art. Cinematic narratives shape perceptual states that gently prepare us to accept fiction as though it were reality.

In Portugal, we have our own mythical constructions long mistaken for truth, yet which remain precisely that: fabrications. The very founding of the Portuguese kingdom rests, in part, on one such legend—the “Miracle of Ourique.”

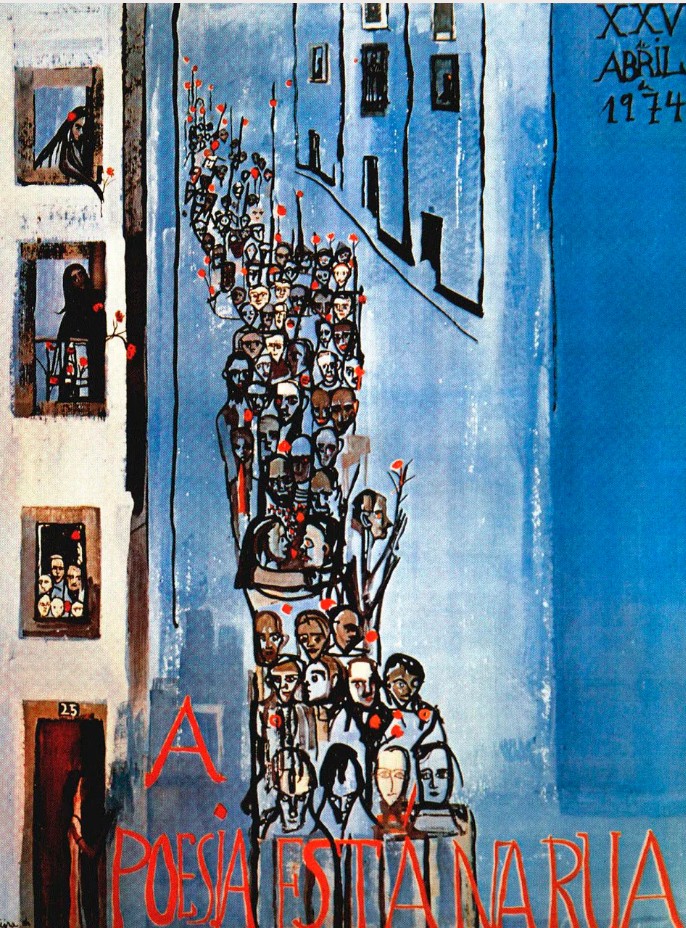

Today (or rather, yesterday), the calendar marks the twenty-fifth of November, and some citizens choose to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of this date as if it were a decisive milestone in our recent history—often granting it more significance than the very day that founded Portuguese democracy: April 25, 1974.

There are many interpretations and opinions, but, like cotton, facts do not lie. I will mention only a few, which unequivocally demonstrate that the events of fifty years ago do not validate the narratives of the right, much less the far right—those nostalgic for an authoritarian regime:

i) there were no changes to the composition of the VI Provisional Government, led by Admiral Pinheiro de Azevedo. The government in place on November 24 remained the same on November 26;

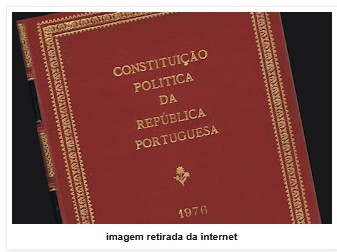

ii) the President of the Republic was not deposed; the Constituent Assembly continued its work and approved the Constitution (CRP) on April 2, 1976;

iii) the CRP enshrined the achievements of the April Revolution;

iv) the CRP was approved by a broad majority, though it could have passed by simple majority. Unanimity was impossible due to the CDS vote against.

The events of November 25, 1975, were essentially military and, unlike April 25, 1974, saw no popular mobilization. The population remained watchful but did not participate. It was a somber day, starkly contrasting with the joy and sense of collective relief that swept the Portuguese people on and immediately after April 25.

The 25th of November 1975 did indeed possess a counterrevolutionary character, in the precise historiographical sense of the term: its purpose was to halt the deepening of the revolutionary process. The military protagonists belonged to the so-called moderate wing, whose aim was to eliminate the political role of the MFA—an objective they achieved through the removal and imprisonment of numerous MFA officers. The revolutionary movement suffered a decisive blow; yet these measures were insufficient to extinguish the transformative momentum that had animated Portuguese society. That momentum ensured that the conquests of April were ultimately secured in the CRP.

While the events of November 25 curtailed sectors intent on advancing a socialist process, it is equally true that they did not immediately reverse the trajectory set in motion on April 25. On the contrary: the popular mobilization sustained over more than a year explains why the newly won social rights were not dismantled by the civil or military authorities that followed.

The first legislative elections—held on April 25, 1976—served to “institutionalize” representative democracy. The political landscape was clear: the PS won, followed closely by the PPD/PSD; the PCP asserted itself as the third force; and the far right had no electoral expression. The right, organized primarily under the CDS, held only modest institutional representation. This reality does not align with the narrative of an alleged right-wing victory on November 25, 1975. No historical evidence supports such an interpretation. If anyone could be said to have prevailed politically, it was the forces advocating democratic socialism, a mixed economy, and the labor and social rights secured since 1974.

Shortly thereafter, on June 27, 1976, the first presidential elections were held. General Ramalho Eanes won, supported mainly by the PS and CDS, and widely perceived as a balanced and moderate figure. Eanes was neither a revolutionary nor a nostalgist for the Estado Novo.

From that point forward, however, a process began that deserves careful consideration. The 1976 Constitution enshrined principles directly rooted in the transformative energy of 1974–1975: the path toward socialism, the irreversibility of nationalizations, agrarian reform, advanced labor rights, the role of workers’ commissions, universal healthcare, and education as a fundamental right. But from the early 1980s onward—beginning with the 1982 constitutional revision and especially that of 1989—a long erosion of the achievements of April commenced.

This dismantling was not abrupt. It was gradual, externally negotiated, and institutionally legitimized. It began with the removal of the MFA’s political power (which still had constitutional standing), continued with the elimination of the Council of the Revolution, advanced through economic liberalization, and culminated in mass privatizations that reversed the logic of the mixed economy. Over time, constitutional revisions transformed the CRP from a bold, coherent, programmatic text into one increasingly aligned with the dominant ideological winds of the European and Atlantic spheres. From this juncture onward, Portugal entered definitively onto the neoliberal path that would shape subsequent decades—placing us, once again, before spiraling inequalities, precariousness, and a weakened public sector.

This is why revisiting this date requires rigor and critical memory. No epic reframing, no opportunistic revisionism, no journalistic simplification can erase the essential: Portugal became a democracy thanks to April 25; it consolidated that democracy through popular participation and the social achievements of 1974–1976; and only years later—well after the events of November 1975—did a political process begin that gradually amputated some of the April achievements from both the Constitution and the daily lives of the Portuguese people. History is far more complex than fabricated plots. And when narrative threatens to overwhelm reality, the best antidote remains the simplest of tools: facts, memory, and critical thinking.

Ponta Delgada, November 25, 2025

Aníbal C. Pires, in Diário Insular (in Portuguese), November 26, 2025

Translated by Diniz Borges