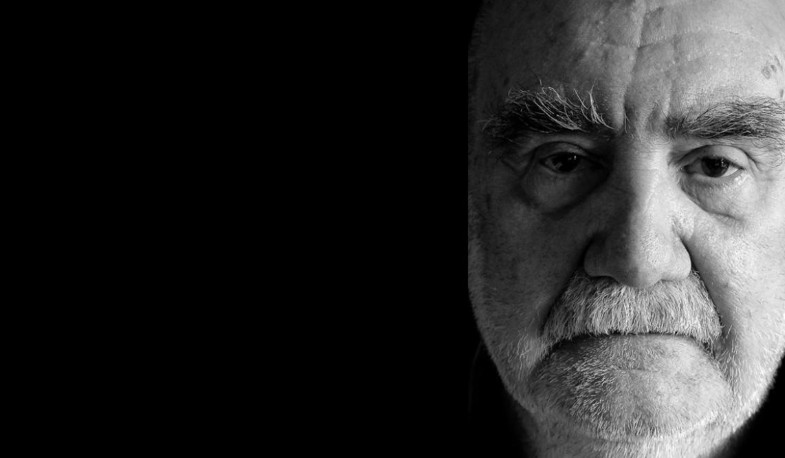

Herberto Helder de Oliveira, born on November 23, 1930, in Funchal, Madeira, remains one of the most enigmatic and revered figures in twentieth-century Portuguese literature. A poet of volcanic intensity—fitting for an island born of fire—Helder became, over time, a legend not merely for his writing but for the fierce privacy that protected it. His life, marked by wanderings, refusals, ruptures, and reinventions, stands as a counter-narrative to the expectations of fame. Yet, despite his insistence on anonymity, or perhaps because of it, he became the poet through whom generations have glimpsed the unsettling, transformative power of language.

Born into a humble family in Madeira, Helder grew up in a landscape shaped by cliffs, wind, basalt, and sea—the same elemental forces that would later infiltrate his metaphors, his rhythms, and his peculiar sense of the body as a vessel of myth. His island childhood was neither romantic nor nostalgic; rather, it provided him with a primordial vocabulary. The rural Madeiran world, marked by labor and mysticism, taught him early that language was not descriptive but incantatory, capable of revealing the hidden life of things.

Like many Madeiran youths of his generation, Helder left the island in search of possibility. He moved to mainland Portugal, where life became a series of beginnings: brief university studies in Coimbra, then Lisbon; odd jobs; and literary circles that would later mythologize his early presence.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Helder lived a life of deliberate rootlessness. He worked as a journalist, editor, translator, and night worker; he lived in Lisbon, Paris, Amsterdam, Copenhagen; he published sporadically, intensely, almost violently. These wanderings were not bohemian postures but essential stages of artistic formation. Helder was always working against any structure—social, academic, aesthetic—that attempted to domesticate him.

His early books, A Colher na Boca (1961) and O Amor em Visita (1958), already revealed a poet unwilling to conform to the norms of neorealism or the more genteel strains of Portuguese modernism. His language pulsed. It twisted. It broke itself open. Portuguese readers had not seen anything quite like it.

From the 1970s onward, Helder became known not only for his poetry but for his refusal to participate in the machinery of literary celebrity. He avoided interviews, declined invitations, withdrew from public readings, and famously rejected the Pessoa Prize in 1994. For Helder, exposure was a distortion. Publicity was a violence against the intimacy necessary for creation. He believed, with almost monastic intensity, that a poem should never be followed by its explanation.

This refusal—strange to some, noble to others—became part of his myth. Portugal, a country that venerates poets, respected his silence. He was left alone to write, revise, rewrite, destroy, and resurrect his own work, creating a corpus that remained in flux across decades.

Helder’s writing is not accessible in the conventional sense. He is a poet of metamorphosis—of volcanic eruptions, bodily transformations, cosmic dissolutions. His metaphors act as living things, not ornaments. His syntax expands with tidal force, creating long, incantatory passages that feel less written than summoned.

Critics often describe him as surrealist, but the term falls short. Helder does not imitate dreams; he enters the underworld of matter and brings back something otherworldly. His poems become inventories of the body, the origins of language, and the incandescent violence of creation. He is the poet for whom poetry is not representation but alchemy.

Herberto Helder died in Cascais on March 23, 2015, but his legacy continues to widen. He left behind a body of work that shaped contemporary Portuguese poetry as definitively as Fernando Pessoa had earlier in the century. With Poemacto, Photomaton & Vox, A Faca Não Corta o Fogo, and the late Servidões, Helder became a point of arrival and departure for younger poets—a kind of lodestar for those seeking a Portugal that is not picturesque but profound.

More than a Madeiran poet, more than a Portuguese poet, Helder has become a continental, even mythic figure: the poet who refused to be seen, so his work could be seen more clearly.

To read Herberto Helder is to confront a Portugal that rarely appears in textbooks or tourist brochures. His work bypasses the folkloric gestures that often dominate Portuguese diasporic memory—saudade as sentiment, tradition as nostalgia—and opens instead onto a landscape of elemental, eruptive imagination. For readers in the diaspora, especially those whose understanding of Portugal is filtered through memory, distance, or myth, Helder offers an alternative map: a Portugal of fire, risk, creation, and metamorphosis.

He reminds us that Portuguese identity is neither static nor ornamental. It is volcanic. Restless. Endlessly reinventing itself.

Herberto Helder stands as proof that literature is not merely a reflection of a nation but one of its deepest engines of transformation. And for those of us scattered across oceans and continents, to read him is to rediscover a Portugal large enough—and fiery enough—to contain the fullness of our imaginations.