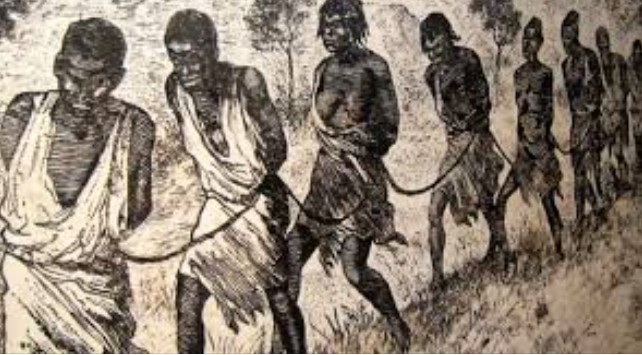

The subject of slavery in the Azores, or even in the country, is almost taboo. It is rarely discussed in society and has not yet been adequately addressed in our schools. In fact, throughout 11 years of schooling, primary, middle school, and high school, I never heard about it, and this year, when I asked my 9th-grade students in the Citizenship and Development class, they said they were unaware of the existence of slaves in the Azores.

Apparently, the silence remained despite the legislation prohibiting talk of slaves, referred to by Ana Barradas in her book “Ministros da noite- Livro negro da Expansão Portuguesa” (Ministers of the Night – Black Book of Portuguese Expansion), which is transcribed below, as being very old and no longer in force:

“Any Portuguese citizen or any individual of another nationality residing in Portuguese territory who intentionally, through speeches delivered at public meetings or through manifestos, brochures, books, newspapers, or other publications intended to be sold or distributed free of charge to the public, disseminates false information in order to demonstrate the existence of slavery or the slave trade in the Portuguese colonies, shall be punished with a fine of 2,000 to 20,000 escudos or with imprisonment for up to two years, and may also be expelled from Portuguese territory. (Labor Code for Indigenous People of the Portuguese Colonies in Africa, December 6, 1928).”

As a teacher of the subject, as mentioned earlier, which includes human rights as one of its topics, I began researching the subject. Last December I attended the recording of the 7th Encontro com História (Encounter with History), promoted by Históriasábias-Associação Cultural, on “Slavery in the Azores (15th-19th centuries).

Listening to Professor Margarida Vaz do Rego Machado talk about the will of one of the greatest merchants of the Azores of his time, NMRA-Nicolau Maria Raposo do Amaral (1737-1816), in which he requested that one of his slaves be kept and well-treated by his children during his illness, I remembered that I had some documents that had been given to me for consultation by a descendant of that businessman.

All the examples mentioned below were taken from the documentation mentioned earlier.

In a letter dated February 7, 1777, addressed to Manuel Correia Branco, NMRA regrets that he cannot be of service because there is no mulatto woman on the island as desired, but that he will make arrangements to “buy one who is not older than 14 years of age, and who is not ugly, and if I can buy her, I will send her to be taught in your house so that she can serve My Lady.“

In a document entitled ”From the 4th Copier of NICOLAU MARIA RAPOSO DO AMARAL (FATHER) copy dated July 25, 1782), regarding the facilities of the “College that belonged to the so-called Jesuits of the island of São Miguel,” that businessman complained that “of the 18 cubicles mentioned above, 12 are for the accommodation of my family.”

And what was family to him?

Here is the answer: “my wife, five daughters, four sons, a nanny, two maids, four female slaves, and servants and three male slaves…”

On May 12, 1784, in a letter addressed to João Filipe da Fonseca, NMRA writes that he may send a ship from Angola to Rio de Janeiro with slaves.

On August 6, 1785, NMRA, in a letter addressed to the same recipient, after writing that he felt “that the spirit of the law must be preserved in these Islands for the freedom of the Blacks brought from our America,” adds the following: “The inconvenience suffered here due to the lack of slaves is incomparable: my house cannot function otherwise, and since Your Majesty tells me so, it seems that I am under a strict obligation to grant freedom to a few who accompanied me from Brazil years ago in good faith.”

In a letter dated August 6, 1785, addressed to João Filipe da Fonseca, NMRA again refers to slavery on the island of São Miguel, as follows:

“I am sorry to hear the news you have given me, that the spirit of the Law must be preserved in these Islands for the freedom of the Blacks brought from our America.

The inconvenience suffered here due to the lack of slaves is incomparable: my house cannot function otherwise, and since Your Majesty tells me so, it seems that I am under a strict obligation to give freedom to a few who accompanied me from Brazil 17 years ago in good faith.”

In a letter dated March 20, 1796, addressed to José Inácio de Sousa Melo, from the island of Madeira, the following can be read at a certain point:

“I am sending Your Majesty a Black slave of mine, named Rosa, who was raised from a young age in this House, where she learned all the duties of her service. I purchased this slave from a daughter of Dionísio da Costa o Marchante, as stated in the deed I am sending to you, along with a certificate of her age and a power of attorney for you to make this sale, either at auction or by private agreement, as soon as you can and as soon as she arrives.

This slave has had no vices until now. Still, I am ordering her to be sold because I know that she has dishonored herself with a slave from this house, whom I believe to be pregnant. If this misfortune had not befallen her, I would not sell her for all the money that might be offered for her, and she would be freed upon my death and that of my wife.

What I am telling Your Excellency is the truth, and I hope that she will find a good house to buy.

Your Excellency will use her net income to pay the amount I am requesting, and you can send me everything by this ship or by another that is leaving for this island. Otherwise, Your Excellency will send it in letters to Lisbon, as I recommend. If Your Majesty wishes to keep this slave, you can do so for ten thousand reis less than the highest price offered for her: that is, if she pleases you.

On October 6, 1797, in a letter addressed to Jerónimo José Carvalho, he mentions owning three slaves. Otherwise, he would be forced to sweep the stable and carry water to his house.

On March 8, 1800, in a letter addressed to João Filipe, NMRA mentions the liberation of slaves “by the pardon of the Law, notwithstanding some Sentences of the Court of Appeal that oblige them to slavery, based on the fact that the Law does not extend to these islands, but only to the kingdom,“ and goes on to state that no one dares to send for blacks from Brazil because they risk losing them.

In 1802, in a letter dated August 8, addressed to Manuel Tomás, he writes that he ”plans to send a brown slave to Lisbon to learn to be a coachman.”

In a letter sent to João do Rego Falcão, from Pernambuco, he writes about two slaves he bought in Ribeira Grande, asking him to sell them because “they have degenerated into the vice of cohabiting with various concubines” and because they have begun to want to revolt against him.

In a letter addressed to the João mentioned above do Rego Falcão, dated November 14, 1804, he places a series of orders, such as honey, cotton, rosewood sticks, etc., and “a well-built Molecão slave, with good legs, who can already carry a barrel of water: being of a good Nation, not Cabondá, Moxecongo, or Mujólo, or other disapproved nations, but rather from the best nations,“ as well as ”three black Moleconas with good faces, girls aged twelve to fifteen years old, more or less, so that they can knead bread and serve a house well, being from good nations as I have recommended, and none from the disapproved races.”

On October 6, 1805, NMRA writes to João do Rego Falcão acknowledging receipt of the requested slaves. Thus, according to him, “the Moleque and Negrinhas arrived alive. The Moleque’s homeland is unknown, only that he is from the Malagueta or Cafraria coast. One Negrinha Cabondá, being from the worst nations, and two Benguelas.”

In 1807, the slave trade continued. In fact, NMRA wrote in a letter to Joaquim José da Fonseca that he “wants to sell a black slave because she mistreated a granddaughter.” He does not want her to stay on the island and asks that she “be sold to a charitable home, even if it is for less than her value.”

When it comes to the abolition of slavery, the first step was taken in Portugal in 1761, through a charter ordering the liberation of all black slaves who arrived in the metropolis. Complete abolition, throughout the territory under Portuguese control, at least on paper, would not occur until February 25, 1869.

Despite the legislation passed, in practice the extreme exploitation of the human workforce continued to such an extent that in a book published in 1944, Norton de Matos, who was governor of Angola, wrote the following: “Slavery continued (…) in Angola and other African colonies, almost to the present day. Concealed, camouflaged, sophistically disguised, it continued to exist, and I would certainly be remiss if I did not state that I found it under various names or disguises in the Portuguese overseas province that I governed in 1912 and the following years.”

History cannot be erased or judged with today’s eyes, especially since slavery continues to exist, with more people in slavery today than in the past. According to the ACEGIS-Association for Citizenship, Entrepreneurship, Gender, and Social Innovation, there are 40.3 million victims of modern slavery in the world, a quarter of whom are children.

If we cannot correct the mistakes of the past, we can act to prevent them from continuing in the present and the future. The first step is to study history, not hide anything from new generations, and denounce all situations of slavery, whether overt or covert.

To learn more:

Barradas, A. (1991). Ministers of the Night—Black Book of Portuguese Expansion. Lisbon: Antígona.

Casas, B. (1990). Brevíssima Relação da Destruição das Índias (A Very Brief Account of the Destruction of the Indies). Lisbon: Antígona.

Mendes, L. (1977). Memória a respeito dos escravos e tráfico da escravatura entre a Costa d´África e o Brasil (Memoir on slaves and the slave trade between the African coast and Brazil). Porto: Publicações Escorpião.

Teófilo Braga