“What does distance matter to us

If that same circumstance

Brings us the land we remember…

And the memories of yesteryear

Have no day, no time—

They have the longing stored away.”

—Francisco do Canto e Castro, Alma Açoriana

Memory begins, for me, with a voice calling across the decades: “Come here, come here! Look, a bag has arrived from America!” My beloved tia Lina cried out like a herald of some far-off kingdom, summoning me—three years old—to my maternal grandparents’ house. There, on that modest island porch, America would spill out of burlap sacks like a myth: the sweet, chemical perfume of new clothes; the cuts of fabric destined to become Sunday dresses; the glow of foreign candies wrapped in impossible colors.

For any Azorean child of the twentieth century, America was never just a country. It was an elsewhere, a shimmering horizon stitched into the fabric of island life. Pedro da Silveira called it our “lost Californias of abundance,” and he was right: the archipelago itself seemed to tilt westward, as if the nine islands were forever listening for news borne on Pacific winds.

Throughout the century, departure became our unwritten epic. We were people shaped by absence, by suitcases packed in silence, by goodbyes spoken on doorsteps where the salt of the ocean mingled with the salt of tears. As Eduardo Bettencourt Pinto wrote, we lived suspended between “the departing kiss” and “the tearful glance.”

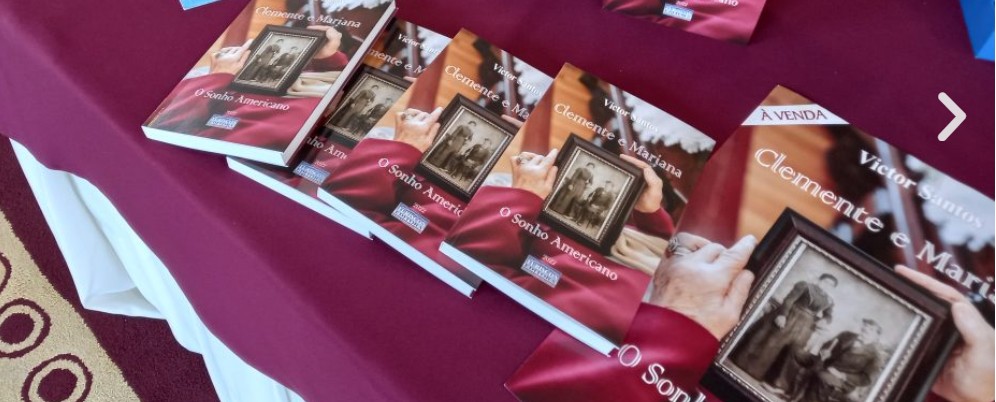

It is on this sacred terrain that Victor Santos sets his novel, a story of one family that is also the story of thousands. Clemente and Mariana are not merely characters; they are archetypes of our collective journey, the distilled essence of the Azorean diaspora. Their lives unravel and rebuild across two geographies—first the United States, later Canada—knotted by longing, steadied by work, and haunted by the islands that remained engraved in the heart’s hidden chambers.

Luck accompanied them, though luck is never equally distributed among those who pursue the American dream with empty pockets and a lifetime of hope. And yet saudade permeates their days—not always as tears, but as that slow, inward ache Virgílio Vieira described so perfectly, when he wrote of “tears rolling slowly along the reverse side of the wrinkles of longing.”

From the first tremors of departure to the dizzying strangeness of arriving in Uncle Sam’s land, from courtship and marriage to the cyclical returns to Terceira Island, from the tumultuous decades in New England’s mills and neighborhoods to old age lived with dignity, their experiences echo the inner geography of thousands of Azoreans who rebuilt themselves in exile.

In those corners of America, they established more than families.

They built islands within the continent: parishes surrounded by English but rooted in incense and rosaries; clubs and festas that pulsed with the drums and smells of home; communities that expanded Azorean identity into something more supple, more hybrid, more luminous. As Onésimo Almeida wrote, they created an “Azorean parish surrounded by America on all sides”—a sanctuary made of language, rituals, and memory.

Mariana’s final years—spent in a warm, welcoming nursing home—attest to this way of being Azorean abroad: hardworking, open to the world, and capable of weaving comfort and dignity from the raw fabric of migration.

Victor Santos’ novel is also a museum of language. The Azorean-American dialect—once mocked by islanders intoxicated with post-1974 modernity as folkloric—is revealed here as a brilliant linguistic tapestry. Before “know-how” and “software” infiltrated Portugal, emigrants like Clemente and Mariana were already forging English-Portuguese symbioses that flowed naturally from necessity, imagination, and identity.

Sadly, these hybrid words and rhythms are fading—lost among younger generations who speak neither the old Portuguese nor the Azorean-English dialects that once filled living rooms from Fall River to Tulare. Victor Santos rescues them, preserving the linguistic fossils that anchor a culture shaped by tides, storms, and departures.

Another vital dimension of the novel is its portrayal of associative life—festivals, brotherhoods, clubs, and pilgrimages. These are not mere embellishments; they are the beating heart of the diaspora, spaces where the past negotiates with the present and where culture thrives without subsidies, without orchestration from Lisbon or Ponta Delgada. The community’s creativity flourished in freedom, shaped by the American landscape and animated by island tradition.

And then there is religion—the great subterranean river running through the Azorean soul. Few chapters in the novel are as exquisite as “Don’t Mess with the Holy Spirit,” which captures with uncanny precision the Azorean pilgrimage to fulfill promises made in times of crisis. The Holy Spirit festivals—whether in Terceira, Massachusetts, or California—remain our diaspora’s umbilical cord, linking generations through coronations, soups, decorated calves, and hymns carried by the wind.

Reading that chapter, I was transported back to 1972, when, after four years of emigration, my father took us to Terceira to keep a promise to the Divine. Those five months shimmer still as the most beautiful of my youth. I felt anew what Álamo Oliveira wrote: “only the taste of salvation—you’re coming to visit this year, and (oh heart!) how good it is to have an American here at home.”

The novel’s timeline deepens its resonance. Clemente and Mariana were among the few who managed to enter the United States after the 1921 immigration law. They began their American lives in the shadow of the Great Depression, learned resilience during the slow recovery, and endured the transformations brought by World War II. These were years when the trickle of Azorean migration faltered, when discrimination existed, yet when solidarity sometimes rose unexpectedly, changing the flavor of life, as it did for Clemente and Mariana.

And yet, reading this novel from the standpoint of the twenty-first century, one cannot avoid a more uneasy reflection: how much of Clemente and Mariana’s spirit has survived in today’s Azorean-American community?

Their world was built on abertura—on welcoming the stranger, helping the newly arrived cousin, sharing food and work, offering a room, a ride, a chance. Their ethic was one of solidarity, tenderness, and reciprocal care. But today, in some corners of our diaspora, that spirit feels diminished. We have allowed the harshness of contemporary American politics—its nativism, its suspicion of the foreign, its exaltation of the “real American”—to infiltrate our own communities.

Ironically, we who were once victims of the anti-immigrant gaze have now, in some cases, learned to wield it. The descendants of those mocked for their accents, their lunches, their faith, now sometimes echo the same rhetoric that once humiliated their grandparents. We have forgotten that Clemente and Mariana arrived with nothing but hope and labor. We forget that their DNA is the DNA of the immigrant experience, scarred but noble, trembling yet brave.

The novel holds up a mirror—not only to who we were, but to who we sometimes are not anymore. It reminds us of a generosity that is fading, of a humility that has been replaced in places by closed mentalities, by meanness dressed up as strength, by the temptation to assimilate not only into America’s opportunities but also into its prejudices.

And yet, the novel also invites us back. Yes, back to the essence of our heritage— to solidarity, caring, sharing, accepting, embracing, and yes, loving.

Clemente e Mariana: o sonho americano (the American Dream) stands as a luminous contribution to the literature of our diaspora. Victor Santos joins the lineage of Azorean voices in America who have written in both Portuguese and English about our saudade-drenched condition—our duality, our bilingual dreaming, our island consciousness carried like a secret ember in the chest.

This novel, like many works of diaspora literature, does not merely recount a story. It carries the weight of a heritage. It preserves what the sea could have swallowed. It sings the epic of those who left and those who remained.

It reminds us that in the Azorean soul, distance is never absence— it is simply another name for the deep, enduring pulse of longing.

And perhaps it calls us, quietly but insistently, to recover what was best in us— to look deep in our eyes and recognize the people we once were

and the people we still have the grace to become.

Diniz Borges

(From the afterword I had the honor of writing for Victor Santos’s novel—now revised, expanded, and adapted into a stand-alone reflection on the book and on our diaspora, past and present.)