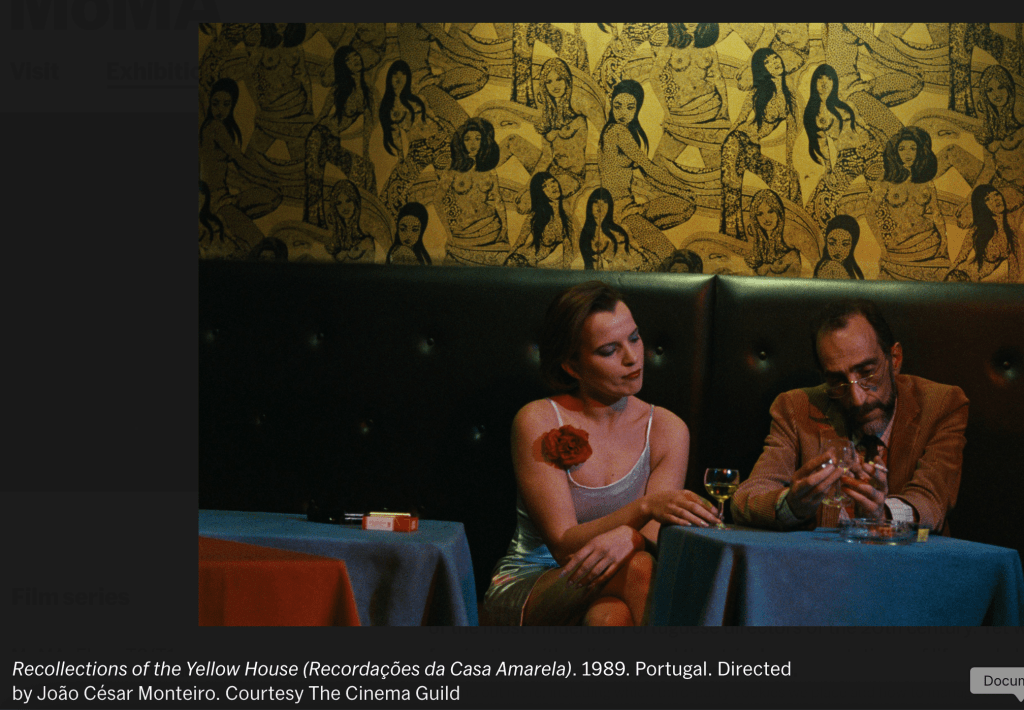

Since October 16th and through November 6th, the Museum of Modern Art has had a retrospect of the Portuguese filmmaker, João César Monteiro. Besides the famed Manoel de Oliveira, Monteiro is one of the most influential Portuguese directors. While Oliveira is associated with neorealism and literary influences, Monteiro is associated with surrealism, anarchy, and “perverted mysteries”. Even without political implications, Monteiro knew how to push people’s buttons. He famously enraged audiences and critics with his film Branca de Neve (Snow White), a movie that is mainly just a black screen and allegedly cost hundreds of thousands of euros from the Portuguese government to make. I was lucky to watch his most acclaimed film in this retrospective, Recordações da Casa Amarela (Recollections of the Yellow House).

Recollections of the Yellow House features a middle-aged drifter named João de Deus (named after the Portuguese patron saint of the poor and mentally ill). João lives at a rundown boarding house where he wanders the rundown historic neighborhoods and ignores an unknown illness he refuses to treat. The only time he visits his aging, and still working, mother is when he needs money. When he is not trying to scrape money for rent, he lusts after any woman that gives him attention. Even the landlady’s daughter is not safe from him. After foolishly making a move on her, the landlady chases him out and he lives on the streets. During this time, he suffers a mental breakdown and hallucinates that he is a high-ranking cavalry officer in the Portuguese Army. I won’t spoil the rest, but João certainly descends more into madness.

This was my first time seeing any work from Monteiro and to call it a unique experience is an understatement. You cannot predict anything that will happen next while watching Recollections of the Yellow House. While some parts were a little confusing for a first-time watch, it is certainly not a boring film. With an anti-fascist and anti-clerical upbringing, Monteiro was an artist who was no stranger to controversies. He believed fascism still existed and continued to grow in power structures of the status quo. Many of his films often used fetishes and violence as symbols of fascism’s legacy in post-revolution Portugal. It takes no talent to shock people, but it takes true artistry to shock with intention. Monteiro is one of those artists.

We thank the Portuguese Times for allowing Filamentos to republish this story. Mathew Arruda has been writing some wonderful pieces for the newspaper, and we are grateful for the generosity of allowing us to share them with our readers.