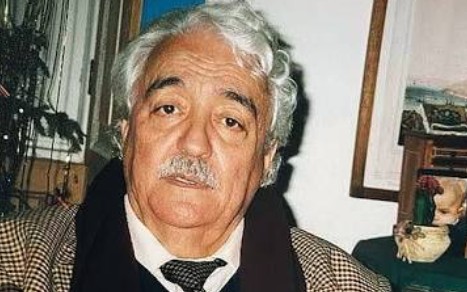

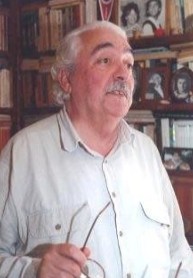

Some poets inhabit the language as one inhabits an island—surrounded by limits, yet looking endlessly toward the horizon. Emanuel Félix (1936–2004), born and deceased in Angra do Heroísmo on Terceira Island, belonged to this rare lineage. His poetry—rigorous, visual, musical—embodies the paradox of the Azorean condition: rooted and universal, insular and expansive, born of solitude but reaching toward the infinite. A painter of words and a restorer of meaning, Félix stands as one of the most distinguished voices of twentieth-century Azorean and Portuguese literature, not through grand gestures but through quiet mastery, precision of image, and the ethical discipline of art.

Beginnings: Gávea and the Plastic Word

Emanuel Félix’s literary journey began in the vibrant post-war cultural atmosphere of the Azores. Together with Rogério Silva and Almeida Firmino, he helped shape Gávea, an Azorean art magazine that became a beacon for modernist sensibilities and critical renewal. In Gávea, Félix published a “Brief Anthology of Azorean Poetry,” already signaling his dual calling as poet and curator. This mind would not only write but also frame and contextualize an entire generation of insular voices.

His first book, Sete Poemas (1958), marks a moment of subtle revolution in Azorean letters. Often identified as a precursor of concretismo—the movement that, in the 1960s, redefined poetic form by exploring the materiality of language—this early collection revealed Félix’s fascination with the interplay between word and image. The poem, for him, was never static; it was a visual field, a space of movement. From the beginning, he sought to transform poetry into a form of visual thought, where syntax and silence create shape, and meaning emerges from balance and proportion.

Later studies in France and Belgium—in art restoration, conservation, and art history—shaped his aesthetic of discipline. Félix learned that the artist’s task was to reveal what already existed beneath the dust of time. As he would later write, the poet and the restorer share the same vocation: to fix the right color, the exact outline, the surviving light.

Dialogues with the Visual and the Musical

Few Portuguese poets have pursued as deep a dialogue between poetry and the visual arts as Emanuel Félix. His 1965 book O Vendedor de Bichos (The Animal Seller) is a gallery in verse. The poems converse with Miró’s vibrant chaos, Picasso’s fractured faces, Lurçat’s woven visions, and Henry Moore’s sculptural voids. Each poem becomes both artifact and gesture—language carved in the air. The poet works not with marble or pigment, but with rhythm and silence.

In As Quatro Estações de António Vivaldi (1965), Félix turned from color to sound, creating sonnets inspired by Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. These poems are not mere literary homages; they are structural symphonies. Their rhythm mirrors the cyclical movement of time and nature, echoing both the musical motif and the existential one. He achieves, through precise language, a neo-baroque harmony of order and surprise—each line as deliberate as a brushstroke, each word resonant with the discipline of music.

In both books, we find the essential Félix: the craftsman of the invisible, the artist who sees poetry as architecture, each word a beam supporting a house of silence.

The Ethics of Labor

With A Palavra o Açoite (The Word the Whip, 1977), Félix reached the full maturity of his voice. Its very title condenses his artistic credo: that language, like labor, demands rigor; that creation is an act of endurance. The poem quoted by Carlos Reis captures the essence of this ethic:

“At dawn the worker /

At dawn the poet /

Gather the most precise words /

For the time that is coming /

While a fiery sun rises.”

For Emanuel Félix, poetry was work—painstaking, physical, exacting. It was not inspiration but construction, not escape but confrontation. The poet and the artisan share the same dawn, the same discipline, the same humility before matter. In this, he joined a lineage of Portuguese writers—from Jorge de Sena to Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen—who saw artistic integrity as a moral act.

Félix’s poems often seem carved out of basalt: hard, minimal, enduring. Yet within that austerity lies immense tenderness. His work resists the sentimental while achieving profound emotion through precision. “The word is the whip,” he seems to tell us, “but also the way forward.”

The Possible Journey

In 1984, A Viagem Possível (The Possible Journey) gathered the essence of Emanuel Félix’s previous work. This retrospective selection reveals a mind constantly returning to its own origins, not out of nostalgia but as part of a metaphysical cartography. The title itself—“possible”—is revealing: Félix accepts the limits of existence, of art, of the island, and finds within them a form of transcendence.

His later collections, O Instante Suspenso (1992) and Habitação das Chuvas (1997), extend this movement toward interiority. The suspended instant becomes both an aesthetic and a philosophical category: the moment where perception pauses long enough for truth to appear. The “dwelling of rains” evokes the Azorean climate—moist, gray, fertile—but also the inner weather of the soul. In these later books, Félix’s voice grows ever quieter, more luminous, closer to prayer.

The rain, the sea, the fog—recurring images of Azorean poetry—become in Félix’s work symbols of continuity and erasure, creation and dissolution. They remind us that life, like art, exists in the interval between clarity and mist.

V. Between the Island and the World

“Emanuel Félix,” wrote critic Vamberto Freitas, “will never be merely a great Portuguese poet from the Azores—he is a monument of artistic persistence, of fearless originality, of Atlantic belonging, a traveler of continuous departures and returns, a discoverer who does not point the finger at anyone but illuminates, with the natural light of an astral body, the world around him.”

Freitas places Félix in the same lineage as Saul Bellow, an artist who made his origins the center of his universality. “Just as Bellow declared he would be faithful to his Jewish-American roots,” Freitas continues, “Félix represents something very similar for the Azores in relation to Portugal, whose territory is far larger and more imaginative than the maps ever suggested.”

To be Azorean, for Félix, was not to be provincial; it was to inhabit a broader moral and imaginative geography. His island was not an endpoint but a beginning, a prism through which the universal could be refracted.

Félix’s poetry thus moves between worlds—the tactile and the transcendent, the Atlantic and the global. He understood that the Azorean experience, when expressed with authenticity, becomes a metaphor for the human condition itself: isolation, endurance, memory, and the search for connection.

The Poetics of Restoration

Beyond poetry, Emanuel Félix was also a restorer of art, a craftsman of patience. He understood that restoration is an act of dialogue with time: one must touch the past lightly, preserving its integrity while revealing its light. That ethos permeates his writing. His poetry restores fragments of perception, reanimates the faded fresco of feeling, and rebuilds the world word by word.

As Freitas notes, his Complete Works reveal a life devoted not only to poetry but to prose—fiction, criticism, and essays on painting, heritage preservation, and Azorean cultural life. To assemble such a body of work, Freitas observes, “requires not only knowledge and critical capacity, but an ethical awareness not always remembered in projects of this kind.” That sense of ethics—rooted in humility, clarity, and responsibility toward the world—defines both Félix’s art and his life.

Even his prose, Freitas reminds us, retains a hypnotic quality: “Emanuel was a great storyteller, captivating listeners with tone, gesture, and silence… recreating characters and situations from his real life. His writing continues to exert the same effect on readers who encounter it for the first time.”

For Félix, the artist’s task was simple but immense—to look closely, to see deeply, to restore the invisible threads between art and life.

A Personal Reflection

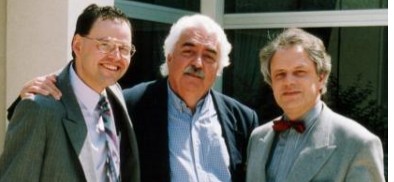

I met Emanuel Félix in 1994. By then, he was already an admired figure in the Azorean literary landscape, yet he carried no trace of arrogance. He spoke softly, with the same precision that marked his verses. We met through a shared conviction: that art should not belong to elites but to everyone. He became part of Filaments of the Atlantic Heritage, a symposium I organized for 12 years —a gathering of writers and thinkers from both sides of the ocean. Félix’s presence elevated the event: his insights on poetry, art, and human dignity were lessons that transcended academia.

He became a friend and mentor who taught me as much about life as about literature. Our conversations—often long, always luminous—would drift from painting to politics, from the metaphysics of rain to the ethics of the artist. We spoke of what we both believed in: the democratization of culture, the idea that beauty must be accessible to all, even if not all choose to partake.

He once said, with that wry smile of his, “Art is not the privilege of the few—it is the right of the attentive.” I never forgot that. His words still echo in my mind when I think about the purpose of poetry in our fractured world.

Every time I was with him in Terceira, I carried with me not only books inscribed in his delicate handwriting but also the enduring conviction that art, when practiced with honesty and patience, can heal the fractures of the human spirit. I have a collection of wonderful letters in his impeccable handwriting, works of art.

Legacy: The Light of Angra

Emanuel Félix’s 121 Poemas Escolhidos (1954–1997), published shortly before his death, stands as both testament and threshold. It encapsulates nearly half a century of disciplined creation—a “possible journey” completed, yet always open to return. His posthumous Complete Works, lovingly compiled by Vasco Pereira da Costa, confirm what Vamberto Freitas described as “a monument of artistic persistence.”

To read Félix today is to rediscover an ethics of attention. He reminds us that poetry is not noise but listening, not accumulation but refinement. Like the restorer he was, he approached words as surfaces to be cleaned until the hidden light reappeared. His verse is quiet, yet behind its stillness lies the vibration of the cosmos.

Félix will forever belong to the luminous company of Azorean creators who turned insularity into universality—Vitorino Nemésio, Pedro da Silveira, Álamo Oliveira, and others who found in the smallness of the island the immensity of the human condition. But Félix is singular in his serene authority: he illuminated without imposing, taught without preaching, and lived as he wrote—with precision, decency, and grace.

Conclusion: The Suspended Instant

Emanuel Félix lived as he wrote: attentively, ethically, and without haste. He believed that beauty required patience, that culture must be shared, and that every poem is an act of restoration—a small repair in the vast, weathered fresco of human experience. His poetry is the art of sustaining the instante suspenso—that fragile space between perception and silence, between the island and the infinite.

He remains, as Vamberto Freitas so eloquently put it, “a discoverer who illuminates with the natural light of a star, saying without saying—look, I have seen, there is more world beyond us.”

And for those of us who were privileged to know him, his light still burns in memory: a steady flame of intellect and kindness, of art and humanity, teaching us, even now, how to see

Diniz Borges.

This is an adaptation from an essay in Portuguese written a few years ago, with the addition of segment titles.

Today, October 24th of 2025, Emanuel would have been 89 years old. He died at the age of 67. All of us who were (still are) his friends miss him tremendously.