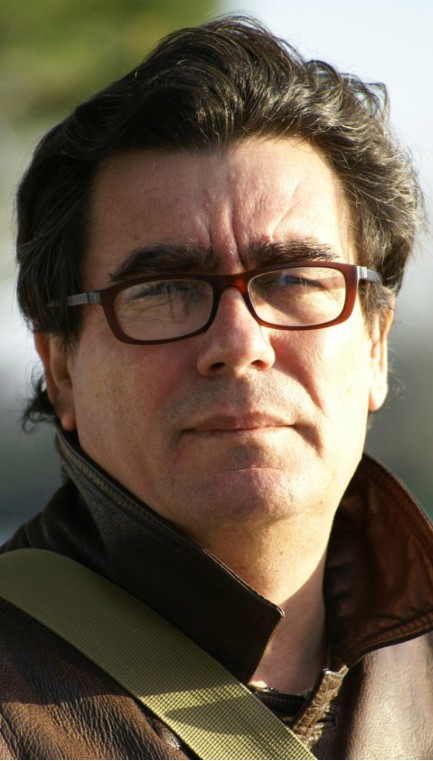

Armando Moreira, a multifaceted artist who moves between painting, theater, and writing, argues that all art forms share the same creative impulse. In an interview with Correio dos Açores, the playwright and writer talks about his search for his own style, the importance of preserving Azorean cultural roots, and his new book, Armandinho – O Caçador de Nuvens (Armandinho – The Cloud Hunter), a historical portrait of Vila Franca do Campo that blends research, fantasy, and autobiography.

A critic of “acculturation” and an advocate of the separation of political power and culture, Moreira laments the loss of traditions and warns of the need to “water our roots.”

Correio dos Açores – You are a painter, sculptor, playwright, screenwriter, and essayist. How do you manage the coexistence of so many forms of artistic expression? Is there a meeting point between them in your creative process?

Armando Moreira (writer and playwright) – Absolutely. Images and words are always connected. Cinema without words was silent cinema; cinema without set design was insipid. Set design must always be present. Scenes today are different; technology has changed. Wonderful worlds are created, and editing itself allows for truly amazing results. All these languages come together and end up refining my gaze, helping me to present works that I hope are of high quality. But above all, refined works.

My spirit of self-criticism is much more severe than that of any individual involved in these processes. I am extremely self-critical of what I do. You can’t please everyone; the important thing in any of these artistic fields is to create your own mark, your own style. Even if that style displeases many, it is what immortalizes the author.

My writing has influences that come from theater, essays, and fiction. This fusion is not always easy to appreciate. Critics sometimes have difficulty with it. When human beings do not understand something, they tend to reject it. We live in a certain cult of mediocrity: when people do not master a craft, they end up improvising… and not always in the best way. I, on the contrary, prefer to be sure that execution is, above all, a matter of having the technical and intellectual capacity to do so.

Your historical research has been important for the preservation of Azorean identity. Christopher Columbus appears frequently in your work and research. What does this figure represent to you?

In Santa Maria, I have already done my part. One day, I was told about a phenomenon that occurred in the 15th century, known as the Escravos da Cadeinha (Slaves of the Chain): two hundred and twenty-five people taken into captivity in Algeria. Through the intervention of the Spanish Court, three years later, these souls returned to the island of Santa Maria, which was deeply marked by their return. I was then asked to reactivate the Association of Our Lady of the Angels, founded precisely by these survivors, which is the oldest association in the Iberian Peninsula. I researched the subject and published four books, available in Santa Maria. I traveled to Algeria, where these Azoreans were sold like cattle, and carried out fifteen historical reenactments in Lugar dos Anjos, mobilizing the entire island.

That area should be classified as historical heritage, but that has not yet happened. In Santa Maria, I did everything in my power. Everything concerning Christopher Columbus and his passage through the Azores is published in my books.

I also carried out research in Santa Cruz, in Lagoa, the place where, under the guidance of the Infante, the Templars began to settle the island, and not in the old Povoação, which they never managed to conquer by land. It all started in the ports of Carneiros and Santa Cruz, next to the old lagoon, which was very different from what we see today. All this documentation is archived in the Library of Tomar.

My book “Açores, o Enigma” (The Azores, the Enigma) has been out of print for a long time and has been translated into several languages. This research eventually brought me closer to the Priory of the Knights Templar of Tomar, who contacted me and invited me to join the Order of Christ, with the title of Commander. I will soon be present at Westminster Abbey in London, where Princess Diana was married.

The Azores have a formidable history, a secular and multicultural culture of incalculable value. When people ask me what is being done to preserve Azorean culture, I reply: very little. Unfortunately, people tend to despise their own culture.

Throughout your vast experience in different artistic and cultural areas, what significant changes have you observed in Azorean culture?

I think we are undergoing a process of acculturation. The cultural development of a land begins with the preservation of its roots, and unfortunately, little has been done in this regard. On the contrary, it is being destroyed.

Where is the popular theater of São Miguel? In the past, every parish had its own theater group. On Terceira Island, they still preserve the bailinhos, but in São Miguel, practically nothing remains. We have something extraordinary that even the Templars admired: the cult of the Holy Spirit. This tradition is based on giving and sharing: giving meat, bread, wine, offering generosity, and communion. It is a wonderful practice. But what has been done with its profane part? Instead of valuing it, we see city councils financing superficial events, hiring Portuguese and foreign artists to sing empty or even obscene lyrics at parties where the main thing is to drink beer. They call this “culture.” In the past, there was popular theater, which could have evolved, transforming itself, while always maintaining its function of social and artistic intervention.

Many mayors have no cultural sensitivity. And the problem is that culture is tied to politics, when in fact it should be independent. It is political decisions that determine what is or is not considered culture, and that is a serious mistake.

Here in the Azores, we cannot depend solely on DRAC subsidies. We have philharmonic bands, yes, but what else? A theater company has never been created. The Conservatory works, it’s true, but there is a certain elitism that distances it from the community.

What is missing is a structured cultural project that truly invests in music, theater, and writing. We have excellent writers and artists, but we lack opportunities and vision.

No government has presented a solid plan for culture. In Cape Verde, culture is valued and well treated; in Madeira, we had João Carlos Abreu, who knew how to transform the island, offering culture to tourists, and not just poncha and espetadas. We Azoreans have deep roots, but they are withered, sinking deeper and deeper. If we don’t water them, we will be culturally bankrupt.

Personally, I have distanced myself a little from this struggle. I receive my salary, write my books, participate in international literary festivals, travel, and teach. I also work in restoration in Prague, in the Czech Republic, in churches. I’m fine with that. I’ve done my part, and there’s no point in wearing myself out with what cannot be changed.

You recently launched the book “Armandinho – O Caçador de Nuvens” (Armandinho – The Cloud Hunter). Can you tell us what the book is about, how the idea came about, and how the writing process went?

The book “Armandinho – O Caçador de Nuvens” came about as a result of a challenge set by Professor José Estêvam Pacheco de Melo, then mayor of Vila Franca do Campo. The invitation was to delve into popular culture: to collect linguistic expressions, customs, traditions, everyday stories, in other words, the soul of a people.

For years, I made recordings and conducted interviews, many still on cassette tapes, and began to write. The work was given the provisional title “Corpo Santo” (Holy Body), in honor of a small beach in Vila Franca. Later, with a new mayor, I resumed the project and decided to give it a new dimension.

The material collected was vast. The book ended up becoming a historical and human portrait of Vila Franca do Campo, the former capital of the Azores and the scene of naval battles, a devastating earthquake, and an intense cultural and commercial life. Because it was “franca” (free), Vila Franca was a tax-free port, attracting merchants from all over the world.

The book also contains the memoirs of Armando Côrtes-Rodrigues, as well as local customs and traditions, including ancient witchcraft practices (the herbs and potions that certain women were said to use to “eliminate” their husbands). It was a wealth of information that could not be forgotten.

Later, I rewrote the book so that it was not limited to Vila Franca do Campo. The result took on a “semi-autobiographical” tone: the story of a boy who was born in Vila Franca and who, after traveling the world, returns to relive the dramas and charms of his homeland. It is also an evocation of a time, of the washerwomen in the communal tanks, of the social differences between the boys of the sea and the girls of the elite. But there is also Africa… my Africa, where I lived and grew up, and which deeply marks the book.

Deep down, “O Caçador de Nuvens” is just that: the vision of a dreamy boy, someone who believes it is possible to make the impossible possible. To be a “cloud hunter” is to live with that enchanted gaze. The title has a real story behind it. At the age of 16, I went to Africa, more precisely to Angola (Catumbela, in Benguela), where I met a 15-year-old German girl, the daughter of farmers. We fell in love like two teenagers: a true Romeo and Juliet. When Angola’s independence process began, she had to return to Germany, and I stayed. I ended up being arrested and mistreated by the MPLA, and, already in the Azores, I became seriously ill with tuberculosis.

Years later, while working in the Merchant Navy, I decided to look for her. I only knew she was in Munich, and I left with almost no money.

On a rainy autumn afternoon, I was standing there, on one of the streets of Rossio, when I saw some papers being blown away by the wind and an old hat. I picked up the hat and some papers and thought: What am I going to do with this? Sometimes, we have divine things like this. I picked it up, looked at it, and, so that one of the sheets wouldn’t fly away, I put my foot on it. I held the hat against my chest and stared at the sky. Pathetic, completely pathetic, I looked like a harlequin, a street performer performing for no one. And I was. A very well-dressed man, wearing a tie and overcoat, approached me and asked what I was doing. I replied, “Can’t you see? I charm and catch clouds.” He smiled and wanted to know more: “Oh, really? And what does this one do?” I told him, “Look, I’ve even caught an angel.” “And what did you do to it?” he asked. “I let it go.”

I got there. I found her. She had had a daughter, but was now married to another man.

This is one of my stories, and it is told without artifice, with the truth that life imposes. The book, however, goes far beyond this story: it is many lives, many memories, more than 300 pages that cross reality and imagination.

José Henrique Andrade is a journalist for Correio dos Açores, Natalino Viveiros, director.