Brazil’s independence, proclaimed on September 7, 1822, was not thunder and fire, but rather a gesture—an intimate cry beside the Ipiranga River that marked a passage more symbolic than violent. Yet the true independence of Brazil, the one that still breathes, has always lived in words. It has been written not only in laws and proclamations but in poems, novels, and stories. Brazil’s identity is less a monument of marble than a song unfolding across centuries—a living poem shaped by the voices of its writers.

José de Alencar, often called the father of Brazilian literature, sought to craft a national epic. His novels—O Guarani (1857), Iracema (1865), and Ubirajara (1874)—offered indigenous heroines and landscapes that pulsed with vitality. In Iracema, he writes: “Iracema era a virgem dos lábios de mel, cujos cabelos eram mais negros que a asa da graúna.” This lyrical vision declared that Brazil’s myths need not be borrowed; they were already written in the forest, the rivers, and the first peoples of the land.

If Alencar gave Brazil its myths, Gonçalves Dias gave it its longing. From exile, he wrote Canção do Exílio (1843): “Minha terra tem palmeiras / Onde canta o sabiá.” These lines became an anthem, embodying the saudade that ties Brazilians to their homeland. For Dias, independence was both emotional and political—a right to love one’s country as singular, irreplaceable, and eternal.

Machado de Assis, rising from poverty in 19th-century Rio, exposed the contradictions of a society that prided itself on independence but was bound by inequality. In Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (1881), he wrote: “Não tive filhos, não transmiti a nenhuma criatura o legado da nossa miséria.” With irony sharper than any blade, Machado showed that independence without justice is hollow, a fragile mask over deep inequities.

Where Machado whispered, Castro Alves thundered. Known as the “poet of the slaves,” he gave poetry the force of rebellion. In O Navio Negreiro (1869), he roared: “Existe um povo que a bandeira empresta / P’ra cobrir tanta infâmia e covardia!” For Alves, the nation could not call itself free while slavery endured. His verses burned like torches of abolition, insisting that liberty must be universal.

At the turn of the century, Euclides da Cunha gave voice to Brazil’s forgotten. In Os Sertões (1902), chronicling the Canudos War, he wrote: “O sertanejo é, antes de tudo, um forte.” With these words, the backlander became a symbol of endurance, and Brazil’s independence widened to include not just the elite cities but the strength and dignity of the hinterlands.

The modernists carried independence into new forms. Manuel Bandeira, in Vou-me embora pra Pasárgada (1930), dreamed of an imagined land: “Vou-me embora pra Pasárgada / Lá sou amigo do rei.” His verses remind us that freedom is not only political but also personal, a dream of dignity, joy, and possibility.

Cecília Meireles, in Romanceiro da Inconfidência (1953), honored the martyrs of a failed uprising and distilled the dream of freedom: “Liberdade — essa palavra / que o sonho humano alimenta.” For her, liberty was not a possession but a pursuit, renewed in each generation and nourished by the imagination.

Jorge Amado’s novels gave voice to Bahia’s rhythms and struggles, revealing that independence must be lived in culture as much as in politics. In Capitães da Areia (1937), he wrote of street children abandoned by society: “A vida é dura, mas é mais dura se não houver esperança.” Amado insisted that freedom was not only an abstract right but the everyday dignity of the people.

Brazil’s independence did not end in 1822—it began then, and has been rewritten ever since by those who dare to imagine it anew. From Alencar’s Iracema to Gonçalves Dias’s sabiá, from Machado’s irony to Castro Alves’s thunder, from Euclides’s sertanejo to Cecília’s eternal word liberdade, Brazil’s writers have made the nation into a living poem.

On this September 7, let us remember: Brazil’s true independence is not merely a political decree but a chorus of voices—voices that dream, denounce, and hope. The nation is not only territory but text, not only memory but imagination. Each verse, each novel, each line is another declaration of independence, still unfolding.

Brazil is, above all, a poem that has not yet ended.

Happy Brazilian Independence Day.

For more information, take a look at this outstanding documentary on Brazilian Literature…

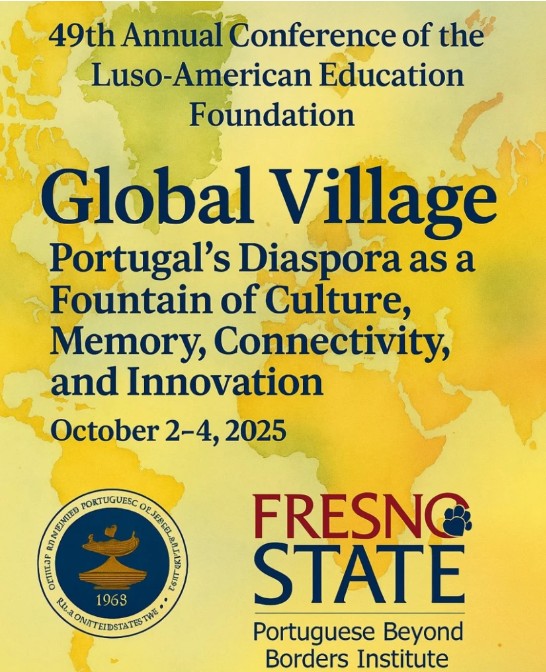

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for continuing to support PBBI-Fresno State.