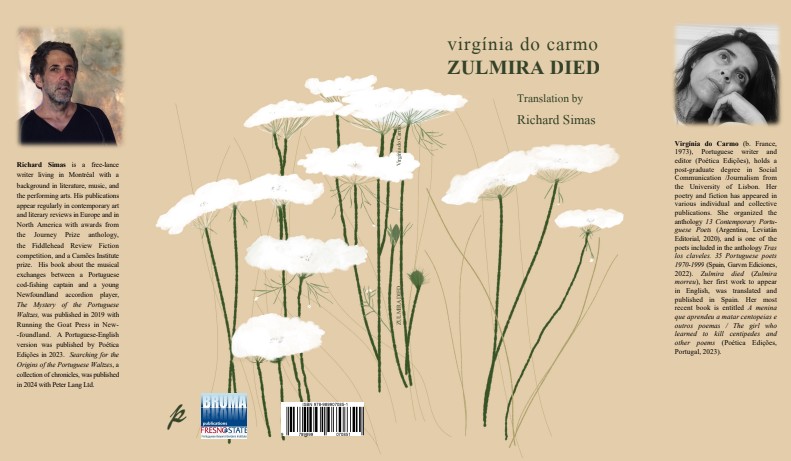

Some books arrive not as storms but as tolling bells, reverberating across our interiors, calling us to listen to the lives we have allowed to slip into silence. Virgínia do Carmo’s Zulmira Died is one such book. It does not whisper; it tolls through the quiet towns and broken kitchens where women’s stories too often vanish without remembrance. It is a narrative born of courage—an act of literary witness that transforms one woman’s tragedy into a polyphonic song of memory and resistance. In Richard Simas’s luminous English translation, Zulmira’s life and death cross oceans, ensuring that her story is not confined to the murmurs of a Portuguese village but now belongs to a global community of readers.

The first act of bravery lies in the very decision to write this book. Virgínia do Carmo begins with an admission: she first encountered Zulmira in death, through the pages of a local newspaper, and could not let her rest there. To reclaim Zulmira’s life from gossip, stigma, and oblivion is to resist the complicity of silence. The narrative does not shy away from the raw edges of violence and despair—it confronts them with relentless tenderness. To write, “Zulmira had difficulty deciding how to die”, is to risk encountering a reality most societies prefer to turn away from. This courage is not sensationalism but moral insistence: women like Zulmira, scarred by abuse and neglect, deserve more than silence.

Virgínia do Carmo threads together themes of stigma, abuse, resilience, and the inheritance of trauma. Zulmira grows under the shadow of illegitimacy—“They called her Zulmira, the bastard”—a wound that shapes her path toward dependence and vulnerability. Domestic violence is rendered without romantic filter: “The day Elias beat Zulmira for the first time, a tremor shook her body… the left side of her face was marked forever by the shape of Elias’ fist”. Against this brutality, Zulmira’s love for her children burns with sacred intensity. In José’s blindness, she sees fingers that “are a miracle from God”; in Vera’s disorientation, she aches for her daughter’s lost compass. Motherhood here is both salvation and sorrow, binding Zulmira to life even as despair corrodes her.

Zulmira Died belongs to a literary lineage that refuses to allow women’s suffering to remain unspoken. In the American context, it resonates with Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, where domestic violence and systemic oppression are transmuted into letters of survival. It also recalls Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina, a novel that, like Zulmira’s tale, traces the scars of illegitimacy, shame, and the cycle of abuse. In both Walker and Allison, we witness women who confront worlds stacked against them, yet whose humanity refuses to be reduced to victimhood. Virgína do Carmo’s Zulmira stands in this same tradition: a woman defined neither by her wounds nor by the silence that her community tried to impose, but by the fragile radiance of her persistence in love, especially through her children. What sets Virgínia do Carmo apart is her refusal to offer redemption or escape—Zulmira’s story remains unflinchingly tragic, which makes its telling all the more necessary.

Yet Zulmira’s story also emerges from a distinctly Portuguese and European current of women’s literature. One can trace affinities to the feminist interventions of Maria Isabel Barreno, Maria Velho da Costa, and Maria Teresa Horta in Novas Cartas Portuguesas (1972), which broke the silence imposed on women’s voices under Portugal’s dictatorship, and which scandalized both censors and patriarchal traditions. Like those writers, Virgínia do Carmo insists that the intimate lives of women—marked by abuse, stigma, and desire—are themselves a terrain of political struggle. In a broader European sense, Zulmira Died also recalls the stark, lyrical prose of Annie Ernaux, particularly in A Woman’s Story, where memory and testimony overlap in acts of reclaiming lives consigned to invisibility. Virgínia do Carmo, however, binds her narrative to the soil of the Portuguese town, imbuing Zulmira’s story with the rhythms of local gossip, rural hardship, and Catholic-inflected shame. This grounding in the everyday makes Zulmira’s tragedy not only emblematic but inescapably real—a life lived and lost among us, not an abstraction.

The author’s prose is suffused with lyricism, balancing brutality with a sense of beauty. She does not simply narrate events; she composes them into images that wound and heal simultaneously. When Zulmira proclaims that “happiness goes barefoot”, the reader is reminded of her fragile yet luminous philosophy: that even amid suffering, life holds the touch of grass, snow, and sand. Richard Simas’s translation carries this lyricism into English with precision and grace, ensuring that the musicality of the Portuguese original is not lost but reborn. He captures not only meaning but rhythm, the pauses and cadences that allow Zulmira’s voice to speak beyond death. It is particularly important that Bruma Publications from PBBI-Fresno State, in partnership with the Portuguese publishing house Poética, collaborated on bringing this story to the American and Canadian readers.

To read Zulmira Died is to walk barefoot across broken ground, feeling every shard of glass and every petal of tenderness. It is a book that insists on memory, on saying the unsayable, on refusing to let Zulmira disappear into the quiet statistics of tragedy. In Virgínia do Carmo’s hands, Zulmira becomes more than a single story—she becomes the echo of countless women who died too young, unnamed, unheard. And through Richard Simas’s translation, her echo now resounds in English, reaching the hearts of readers who will carry her voice further.

The courage of this book is not only in telling the story, but in demanding that we remember, that we feel, and that we never again confuse silence with peace.

You can order the book through Bruma Publications