From Islands of Saudade to a Multicultural Identity in the Golden State

Oceans Between, Roots Within

Footsteps of the Azorean Diaspora in California

Throughout the centuries, the islander has been a wanderer of necessity. Our story begins with the restless sea, that eternal horizon that both confines and liberates. From the 19th century onward, the Azoreans—like their Madeiran and mainland Portuguese kin—were drawn westward, carried first by whaling ships, then by the golden mirage of California, and always by hunger for bread, for space, for justice. It was emigration, not only of desire but of deprivation, born from volcanic stone and meager soil, from the impossibility of survival without crossing the waters.

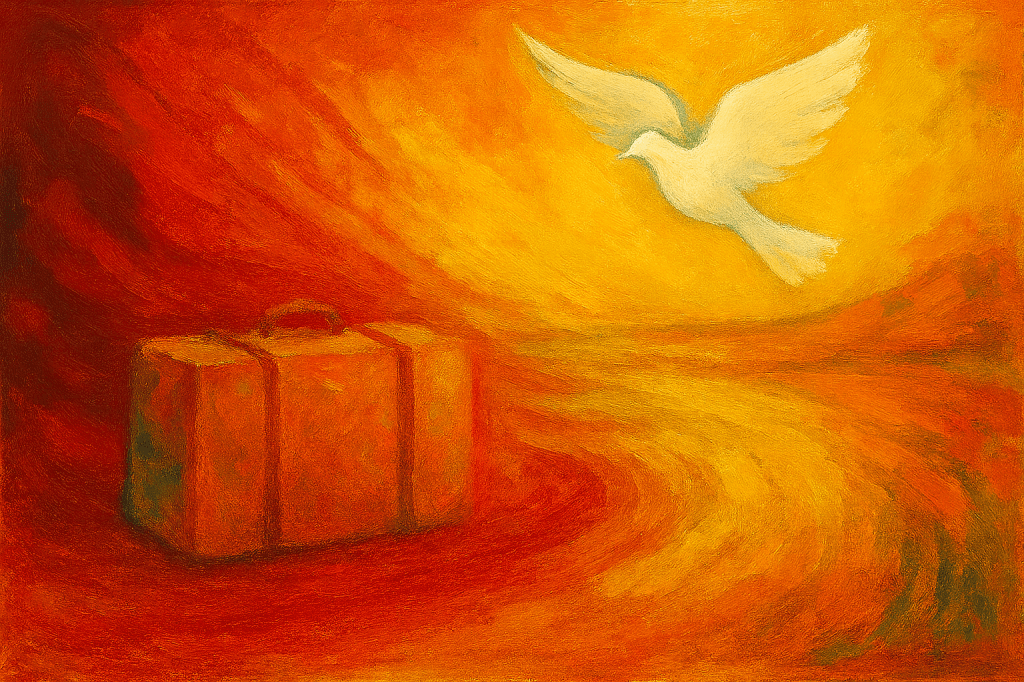

They left their ridges of green for valleys of dust, their ocean for an inland sea of orchards and vineyards. In their suitcases, tied with rope and filled with more longing than clothing, they carried the dream of returning rich, triumphant, ready to lay comfort at the feet of their homeland. But as tides decide more than the sailor, so history decides more than the emigrant. Most stayed. And in staying, they rooted themselves in California’s diverse land, grafting nostalgia to modernity, island song to Californian polyphony, until a new identity bloomed: Azorean-Californian, half memory, half reinvention.

From 1870 until the iron gates of immigration laws closed in 1921, ships ferried thousands across the Atlantic and trains carried them across a continent, all the way to a California that seemed inexhaustible in promise. They built dairies, planted vines, tilled soil that was not their own, and in the “lost California of abundance,” they recreated fragments of their islands—processions, brotherhoods, rituals—holding tight to what they could not leave behind. The silence that followed, when immigration all but ceased, was broken again in the 1960s, when hardship and volcanic eruptions sent another tide of islanders west. By then, the first generations had already grown into Californians; the new arrivals entered valleys where Portuguese was still spoken, where festas rang out, and where antagonisms between “old” and “new” softened over decades into kinship. Together they became a chorus, carrying echoes of their islands into the multi-ethnic song of California. Nowhere is this song louder than in the festas.

Over Seventy Holy Spirit celebrations now blossom across the state, along with dozens of processions for saints beloved in the Azores—Our Lady of Fátima, Senhor Santo Cristo, Saint Anthony, and Our Lady of Miracles, Our Lady of the Assumption, and Our Lady of the Rosary. What began as very closed rituals has spilled beyond their bounds, into the calendars of towns and cities, into civic life itself. Gustine, Pismo Beach, Turlock, Point Loma, Tulare, San Jose—their economies swell, their streets are filled with parades of queens and entourages, sopas shared beneath the shadow of banners, music pouring from philharmonic bands.

In Fresno, a city of nearly 600,000, where newspapers cover the Holy Spirit with front-page reverence, the festivals have become an integral part of the city’s own identity. Manuel Ferreira Duarte once captured it in his story A Banda Nova: the mingling of routine and astonishment, of Portuguese crowds and curious onlookers, all gathering for a spectacle at once intimate and public. These festas, these luminous gatherings, are more than memory preserved—they are memory transformed. The young queens, whose lips may no longer shape Portuguese syllables, walk beside companions of every background—Hispanic, Anglo, Asian, African-American—proclaiming in their very presence that culture is not a wall but a bridge. Even when priests furrow their brows at the profane meeting of the sacred, the Holy Spirit dances freely, reminding us of the proverb from Terceira Island: the Holly Spirit does not belong to churches (o Espírito Santo não é de igrejas), but to the people.

From Easter until October, the calendar is filled with celebrations: bands and singers who improvise verses in Portuguese, folklore groups that twirl skirts of memory, bodos de leite where milk becomes a sacrament, stages of fado and popular music, and arenas where bulls still run, on ropes and tradition. California, paradoxically, holds more Portuguese bullfights on the ring than the Azores themselves. Dairymen who once arrived with nothing now keep herds and sponsor corridas, embedding this paradoxical ritual into one of America’s most politically correct states. Alongside them, Carnaval dances in the Terceiran style are still around, filling halls with masked joy. These traditions are less about spectacle than about survival—ways for descendants, who may no longer speak the language, to still move to its rhythms.

Yet culture is not only festa. It is also a language whispered in classrooms. In California, Portuguese is taught in just over a dozen high schools and in more than a dozen universities and community colleges. Small numbers, yes, but fertile if we believe language belongs not to government ministries in Lisbon but to mouths that speak it, to those who choose to keep using it, even when institutions look away. Around the language, cultural programs flourish—lectures, concerts, and symposia, such as Filamentos da Herança Atlântica in Tulare, now available online through PBBI at Fresno State, which links sister cities to sister cities, islands to valleys, and scholars to emigrants. And let us not forget the Luso-American Education Foundation conference, which has been ongoing for 49 years. Yes, it is a fragile network, but it holds, spun from devotion more than funding.

And it is also literature—the most delicate and enduring vessel of memory. From Guilherme S. Glória’s early poems to Alfred Lewis’s Home is an Island, from Artur Ávila’s Rimas de um Emigrante to Lawrence Oliver’s Never Backward, the written word has kept alive the exiled heart. Manuel Ferreira Duarte chronicled it, Vamberto Freitas analyzed it, and Mayone Dias recorded its history. Katherine Vaz and Frank Gaspar gave it English wings. As have countless others—David Oliveira, Sam Pereira, Lara Gularte, Millicent Borges Accardi, Anthony Barcellos, José Luís da Silva, Décio Oliveira, Maria das Dores Beirão, Diane Ramos Firestone, Linnete Escobar, Melinda Medeiros, and many more—have shaped a literature that is Azorean in marrow but Californian in expression. Portuguese Heritage Publications of California did the work of preserving and projecting, ensuring that our diaspora’s creativity is not scattered dust but bound books. Bruma Publications, through translations and original work, does its small part. These voices echo beyond community halls into the larger currents of American letters.

And so, in the wide and restless 21st century, the Azorean presence in California stands not at the margins but woven into the fabric of its multicultural identity. We are no longer just dairy farmers, fishermen, or festa organizers—we are professors, poets, journalists, musicians, ag business leaders, politicians, novelists, and community leaders. We are a bridge across oceans and across generations.

What began as exile has become permanence; what started as necessity has become a gift. For ours is a culture that has always known how to endure: roots buried deep in volcanic stone, wings stretched wide across the Pacific sky. We did not bring veneer; we brought marrow. We did not bring an ornament; we brought soul. And with that, we have written ourselves into the great California mosaic—our processions and our poems, our sopas and our songs, carrying both saudade and possibility.

Deep roots, open wings: this is our inheritance, this is our offering, this is our flight toward the future..

Diniz Borges

A bit about this new segment here in Filamentos

The Azorean presence in California is written in tides and valleys, in salt carried across oceans and dust lifted from orchards and dairies. It is a story of crowns lifted to the Holy Spirit and hands bent to the soil, of sopas shared in parish halls and poems whispered in new tongues. Yet these writings are not only chronicles of what has been, or what is unfolding still; they are also questions placed before us. What do we wish to carry forward, and what must we renew? How can saudade become more than longing—how can it become participation, creation, and belonging in the great mosaic of California’s cultures? As the old island saying reminds us, “Deus dá o frio conforme a roupa”—God gives the cold according to the clothing—our community has always found the strength to endure and adapt. Here, memory is not a monument but a living river: one that asks us to reflect, to critique, and to imagine how this diaspora might continue to take root and open its wings for generations to come.

Our vision and mission:

Vision

To illuminate the Azorean journey in California as both history and horizon—honoring the courage of those who left, the resilience of those who stayed, and the creativity of their descendants—while cultivating a critical space for reflection so that the diaspora may continue to grow as a vital part of California’s multicultural identity.

Mission

- To document the history, traditions, and voices of the Azorean diaspora with honesty and depth.

- To apply a critical lens to our cultural practices, institutions, and expressions—celebrating their vitality while questioning where renewal is needed.

- To create a platform for dialogue that links past and future, islands and valleys, memory and reinvention.

- To encourage the Azorean-Californian community to see itself not only as a keeper of heritage, but as an active participant in shaping California’s multicultural present and future.

Remembering, Reflecting, and Reimagining the Azorean Presence in California.