“Where Islands Speak Through Art – From the Heart of the Azores to the Diaspora”

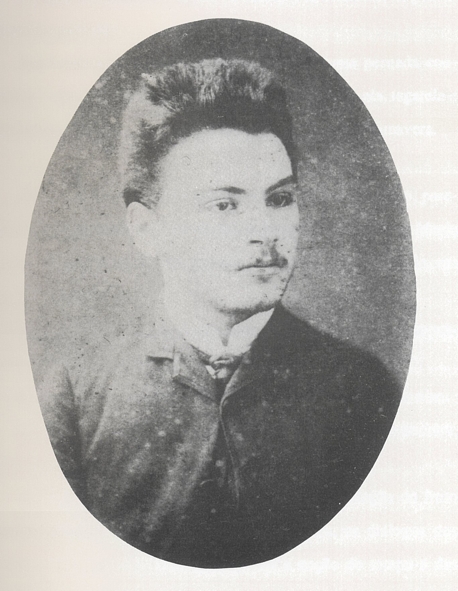

Mesquita, Roberto de

[Born in Santa Cruz das Flores, June 19, 1871; died in the same place on December 31, 1923] Poet.

While many writers feel a disconnect between their time and world and their personal characteristics, Roberto Mesquita was a poet who was born into the right environment and literary era. Indeed, personal, cultural, and psychological characteristics intertwine in Roberto Mesquita’s poetry, with acute sensitivity and rare happiness, the circumstances of life, and the spirit and themes of decadence and symbolism of the literary era.

After attending primary school in Santa Cruz das Flores, the second son of António Fernandes de Mesquita Henriques and D. Maria Amélia de Freitas Henriques, Roberto Mesquita followed in the footsteps of his brother Carlos, a year older, and, like him, after a first frustrated attempt in Angra do Heroísmo, studied at the Horta high school. He then entered the civil service, while his brother, who was also interested in literature, albeit with less success, continued his studies in Coimbra.

In 1890, Roberto de Mesquita, who, in the company of his brother, had already attended some literary gatherings and received encouragement from teachers in Horta, made his literary debut, publishing a sonnet under the pseudonym Raul Montanha in O Amigo do Povo de Santa Cruz das Flores. From then on, he began to publish his poems sporadically: and most of them were published in the regional press (O Açoriano, A Ilha das Flores, Revista Faialense, O Arauto, A Actualidade), while others appeared in some of the most representative national publications of the time, such as Ave Azul or Os Novos, the magazine that gave the most significant expression to the Portuguese symbolist generation.

Roberto de Mesquita, who was an avid reader of Portuguese and French poetry (he was particularly influenced by Verlaine and Rimbaud, but Baudelaire is also present in many of his poems), never lost touch with the literary life of the continent and, on his only trip outside the Azores (1904), he metEugénio de Castro and Manuel da Silva Gaio. These contacts were not unrelated to the intervention of Carlos de Mesquita, a cultured man with a keen critical intuition, who was a teacher at the high school in Viseu and later at the University of Coimbra (he died in 1916).

The publication of his poems in book form was a project cherished by Roberto Mesquita, who organized it and placed it under the express aegis of Antero, entitling it, after Antero’s verse “souls sister to mine, captive souls,” Almas Cativas. However, he died without completing the project, and it was only in 1931, on the initiative of his family, supported by Marcelino Lima, that the work appeared in Famalicão. In 1989, Pedro da Silveira produced a new edition, enriched with scattered poems and a record of variants, with a preface by Jacinto do Prado Coelho. On the other hand, at the end of the 1930s, Vitorino Nemésio considered Roberto Mesquita “the first poet to express something essential about the human condition as it presents itself in the Azores,” finding in his poems the perfect expression of the characteristics that he brings together in his concept of Azoreanity. He was thus able to highlight in the Florense’s book “the best image of the dispersion and drowsiness of life in the Azores, a diffuse and apathetic profile of Azoreanity.”

Some of the most beautiful and expressive maritime poems in Portuguese poetry belong to Almas Cativas. In them, the oppressive weight of loneliness is concentrated in the suggestion of a closed environment, of gray and heavy skies, which extends to the poet in a calm and diffuse way. The ancestral houses and ruins are humanized, the night, with its “mystical musings,” imposes a “sacred terror” while the moonlight transfigures nature. Finally, the poet discovers the “soul of everything praying” and sees his sensitivity heightened by the sunset, the harsh wind, and the ruins that stand out in environments of decay. Invaded by a vague mysticism that far exceeds the spleen evoked in some compositions of the Romantic period, the poet is overcome by melancholy and a sense of loss, which he expresses in a series of images of desolation and decay.sun, by the harsh wind, by ruins that stand out in environments of decay.

Overcome by a vague mysticism that far exceeds the spleen evoked in some compositions, the poet joins forces with the “captive souls” of the universe and takes on the mission of revealing the meaning of nature and things, their “soul.” In doing so, he is aware of his superiority over other men, confined to the simple appearances of the universe; but, as a “cursed poet,” he also finds his misfortune in his gift. Like Philodemus, the shepherd whose wings prevent him from loving, he knows that his condition as a poet prevents him from enjoying the simple and naive joys of ordinary men.

Precisely because he is a poet, he knows he is superior to his contemporaries; and his “omnicoeva” soul, “soul of a dying race, / uncompromising with the withering present,” feels the call of the past. He is therefore interested in the fantastical environments of a past that, festive and unreal, seems to be suspended in the ruined objects that once animated them and have now become symbols, or in the historical or biblical fables so popular in the literary period.

However, it is not a call to the past that pervades the gaze that confuses time and space in the consideration of the distant landscape: it manifests the same state of mind that is externalized in the contemplation of nature and runs through the verses of Roberto Mesquita.

When the sea and the closed horizon of the island are evoked, they are not, however, the direct cause of the boredom and vague feeling of sadness, of the “helpless widowhood” that unites the poet and nature. The night, the distressing northeast wind, or the “macerated closing of the autumn afternoon” certainly stimulate meditation, but his poems do not dwell on a simple search for a psychological understanding of his state. It is rather a religious movement, a pure movement to abolish the separation between the human and physical worlds, which finds its expression in Poetry.

While isolating himself from other men, the poet becomes one with the world. A “you/I” that condenses the opposition with those who are apparently similar to him is followed by a “you/we,” in which the poet feels the closeness of the “soul of things.” And as if to show that the communion between the world and the poet is total, the rhythm of the descriptions of the landscape, in which both a culturally and literarily shaped sensibility and the melancholy of the Azorean spirit resound, is not broken when perplexity manifests itself: “Evening landscape that palpitatingly spies / the shepherd’s star, already floating in the blue? / The causeless longing, the vague nostalgia / That fills this fading day like a perfume, / Was it born in my soul or did it awaken in yours?”

Restlessness is continually reborn from a longing with no definite target or occasional cause. The poet searches in vain to understand its nature through analysis, which is not simply psychological: it is, after all, the result of longing for the ideal (“My soul, where does the sorrow that invades you come from? / What Eden do you feel lost? / Oh! This powerful flood of longing / Without a definite target!”). With every step the poet takes in search of the promises of the absolute inscribed on the horizon, the horizon widens, its line receding into the distance. The realization of any dream results in disappointment, which can only be overcome by fantasizing again about the Beyond.

Reiterated with decadent melancholy, this state of mind is rooted above all in the restless certainty of the final disenchantment of the poet, who cannot help but seek “The essential beauty, forever denied / To our soul that groans on the shackled earth.”

At times, he is overwhelmed by the loneliness of the creature before the Creator: although he senses His presence in the silent immensity of the world, he cannot explain the “cold silence” that responds to the pleas of men, “abandoned on an uncertain path.” But he affirms his belief in a meaning that he never ceases to seek, for the earthly exile that God inflicts on his “little children,” even if it weighs heavily on him to accept “Life fragmented / In lives of a moment.”

And so, although his verses do not systematically reach philosophical depths, the longing they express is not confined to emotion. It is rather the longing for a primordial unity that the poet seeks to decipher in nature and in things, searching for a soul and a meaning that are not offered to either science or ordinary men.

Roberto de Mesquita imposes a symbolic reinvestment of images of island life, isolation, and the “closed sky,” or fantasies of “beautiful regions lost / in the expanse of the sea” that animate some of the most beautiful poems in Almas Cativas. This understanding is so compelling that it becomes impossible to give introspective analysis and feelings about nature any meaning other than that of universality. Even the gentle originality of a style that draws on literary resources typical of the period, but surprises the reader with the tension and suggestive power of its rhythm or the juxtaposition of disparate realities, synesthesia, or unexpected metaphors, accentuates the feeling of indefiniteness, of vagueness, and fosters the dramatic oscillation between the particular and the universal that characterizes a work which, without being very extensive, gives Roberto de Mesquita a place among the great poets of symbolism. Maria do Céu Fraga

Bibliography. In the edition of Almas Cativas for which he is responsible (Lisbon, Ática, 1989), Pedro da Silveira presents, alongside a chronology of the poet, an extensive bibliography with the titles published up to that time. Among these titles, it is fair to highlight:

Vitorino Nemésio, “O Poeta e o isolamento: Roberto de Mesquita” [The Poet and Isolation: Roberto de Mesquita], in Revista de Portugal, no. 6, 1939 (recently republished in a new edition of Conhecimento de Poesia, Lisbon, Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 1997); Jacinto do Prado Coelho, “Pensamento e estesia em Roberto Mesquita” [Thought and Aesthetics in Roberto Mesquita]; Problemática da História Literária, Lisbon, Ática, 1961, pp. 205-209.

In addition, there are: José Carlos Seabra Pereira, Decadentismo e Simbolismo na Poesia Portuguesa, Coimbra, Centro de Estudos Românicos, 1975, José Martins Garcia, O cárcere e o infinito: sobre a poesia de Roberto de Mesquita, sep. de Arquipélago-Línguas e Literaturas, Ponta Delgada, Universidade dos Açores, 1986; Luís de Miranda Rocha, Para uma Introdução a Roberto Mesquita, Angra do Heroísmo, Secretaria Regional da Educação e Cultura, 1981.

Translated by Diniz Borges

in: https://www.culturacores.azores.gov.pt/ea/pesquisa/default.aspx?id=8327

Mission Statement:

“In the Silence of Hydrangeas: Azorean Arts and Letters” is a weekly digital rubric under the Filamentos platform that seeks to illuminate the cultural, artistic, and literary richness of the Azores and its dynamic connection to the Azorean Diaspora. Each week, we highlight writers, poets, musicians, painters, sculptors, theater groups, and cultural movements that have emerged from or been inspired by this Atlantic archipelago. Our mission is to move beyond folkloric clichés and festive portrayals to reveal the profound creative spirit, complexity, and heritage that shape Azorean identity across generations and oceans.

Vision Statement:

We envision a living archive and vibrant stage where the voices, visions, and legacies of Azorean creators—on the islands and throughout the diaspora—are celebrated, preserved, and made accessible to global audiences. This rubric aims to educate, connect, and inspire by showcasing the Azores not as a distant, nostalgic memory, but as a creative force in continuous dialogue with the world. To know the Azores is not merely to attend a festa, but to listen to the poems etched in basalt, the canvases dyed in sea-light, and the stories whispered in the silence of hydrangeas.

Unveiling the Soul of the Azores – One Voice, One Creation at a Time

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for supporting this project