The Azores are more than a cluster of volcanic islands in the mid-Atlantic; they are sites of layered history, political complexity, and cultural resilience. In Azorean History Themes: Islands of Struggle and Resilience, historian Carlos Enes presents a profoundly researched and interpretively bold account of the archipelago’s defining episodes of dissent, nationalism, and identity formation. Through thirteen essays ranging from early modern resistance to the political manipulations of the 20th century, Enes positions the Azores not as passive peripheries, but as active participants in the struggle for Portuguese sovereignty and democratic ideals. As the translator of this collection, I found myself not only immersed in the political currents of Azorean history but also awakened to aspects of my own ancestral memory. These unearthing roots had long been buried beneath the surface of family narratives.

From the outset, Enes foregrounds themes of popular resistance and class dynamics in Azorean history, beginning with Terceira’s 16th-century opposition to the annexation of Portugal by Philip II of Spain. In the titular essay “Terceira’s Popular Resistance to Philip II,” Enes asserts that “a revolutionary process was unleashed, led by the mechanical officers, which overturned the traditional political order in successive stages” (p. 15). Far from depicting a unified, romanticized resistance, Enes details how internal social tensions—between artisans, clergy, nobility, and merchants—shaped the revolt. His portrayal of Brianda Pereira and the symbolic Battle of Salga, where even cattle charged the Spanish, is as vivid as it is symbolic of the people’s raw will to remain free: “That was the day when, if I may use the expression, even the island’s oxen fought for their homes” (p. 32).

A second key theme is the construction and manipulation of historical memory. In “Brianda Pereira: Building the Myth,” Enes examines how a semi-legendary figure of female heroism was elevated—particularly under the Estado Novo regime—to promote conservative and patriotic ideals. He notes that “the image of our heroine… was constructed from the 19th century onwards, drawing more on oral memories than written documents” (p. 11). This tension between myth and document runs through many chapters, especially in the analysis of Francisco Ornelas, whose historical rehabilitation was promoted by the Salazar dictatorship to foster national unity.

Enes’ shift to the 20th century with essays that critique the dictatorship of Salazar and document the rise of democratic dissent. His treatment of the civilian resistance to the Estado Novo is particularly moving in “Citizen Borges Coutinho in the Crosshairs of the PIDE,” where the brutality of the regime’s political police is rendered with chilling specificity. “The imprisonment he suffered did not discourage him,” Enes writes. “He was the main figure in the 1969 elections in Ponta Delgada, in which the CDE… achieved 20% of the vote despite widespread allegations of fraud” (p. 13).

Similarly, “Oldemiro de Figueiredo: The Serenity of a Democrat” traces the quiet perseverance of another key figure, underlining the psychological and moral cost of long-term surveillance and exile. The essays on the Lajes and Ponta Delgada American bases also highlight how foreign powers inadvertently undermined fascist censorship—Lajes, for instance, was “a stumbling block for the institution [PIDE]” due to the free circulation of American media (p. 14).

Several essays pivoted toward the Azores’ long pursuit of political recognition and autonomy. In “Building Regional Unity and Identity,” Enes writes that “Azoreanism, promoted in the 1920s, led to the defense of island interests.” Though often fragmented, the movement crystallized an emerging sense of belonging beyond geographic insularity (p. 12). In “The Azorean Lobby in Lisbon” and “José Bruno Carreiro: The Agitator,” we see how editors, journalists, and cultural activists from the Azores shaped national conversations and challenged mainland-centric governance. Carreiro’s legacy, both idealistic and contradictory, is described as emblematic of an era where “autonomous regime proposals varied according to circumstances” (p. 12). Economic concerns also figure prominently in the later chapters, which explore the impact of global events on the local economy, such as the arrival of American troops during World War I and the transformations of the 20th-century agricultural economy. The final essay, “The Azorean Economy in the 20th Century,” synthesizes decades of socioeconomic change, arguing that the islands “adopted a financial model that has shaped their lives to this day” (p. 14).

Carlos Enes is not only a historian but a novelist and poet, and this literary sensibility infuses his historiographical work with nuance, voice, and human empathy. Born in Terceira, Enes has long occupied a central place in Azorean intellectual life, producing a wide body of work that encompasses archival research, biographical essays, fiction, and historical interpretation. His influences, openly acknowledged in the introduction, lend his work a critical edge, especially in the analysis of class and power: “The reading I still take… is a Marxist one,” he writes, particularly in understanding the “government of minors” and the political protagonism of mechanical officers (p. 11). Enes is not dogmatic. He blends critique with attention to individual agency, showing how figures like Ciprião de Figueiredo and Manuel da Silva navigated competing loyalties and turbulent social currents.

Importantly, Enes never idealizes the past. He highlights the failures of democratic movements, the opportunism of elites, and the dangers of forgetting uncomfortable truths. His historical method is both investigative and interpretive, and his essays are filled with references to archival documents, first-person testimonies, and competing narratives. As such, Enes’s work is not merely a recounting of what happened, but an exploration of what those events have meant, and what they continue to mean for Azorean identity.

As the translator of Azorean History Themes, I found myself retracing not only Carlos Enes’s research path but also my own. Each chapter became a mirror to my own family stories, whose shadows had always lingered in the background but never taken full form. In translating the words of resistance fighters, economic migrants, and forgotten artisans, I began to hear the voices of my ancestors—my avô who rarely spoke of the dictatorship, my tias who remembered the arrival of American soldiers, the murmured prayers of my mãe in a dialect I had once tried to leave behind.

Translating Enes was not just a linguistic exercise; it was a moral and emotional reckoning. Every turn of phrase carried with it a cultural and historical weight. How does one translate the term “arraia-miúda” without losing its sting and solidarity? How does one convey the sarcasm in Ciprião’s rebuke to Ponta Delgada—“even a woman who is not very chaste will not surrender unless she is asked”—without slipping into caricature? (p. 29). The challenge was not only to make the text accessible to English-speaking readers, but to preserve its emotional and political urgency.

This process made me realize that history, when honestly and humanely told, is never impersonal. It becomes part of us, and we become part of its transmission. As I translated, I felt a sense of continuity—not only with Carlos Enes’s voice, but with the many unnamed voices that fill these pages: the artisans of Angra, the children shouting in protest, the women who stoned the Jesuits, the men who were tortured for wanting something as simple as a free election. Their language is now part of mine.

Carlos Enes’s Azorean History Themes is a landmark work that challenges the reader to view the Azores not as idyllic outposts but as crucibles of struggle, resistance, and reinvention. Through his essays, Enes reclaims stories that had been misused, forgotten, or deliberately erased, and in doing so, he affirms the dignity of a people often seen as peripheral. As a translator, I came to see not just the Azores more clearly, but myself—my history, my responsibilities, my voice. This book is more than a collection of historical studies. It is a living archive, an invitation to remember, and a call to continue the work of resilience.

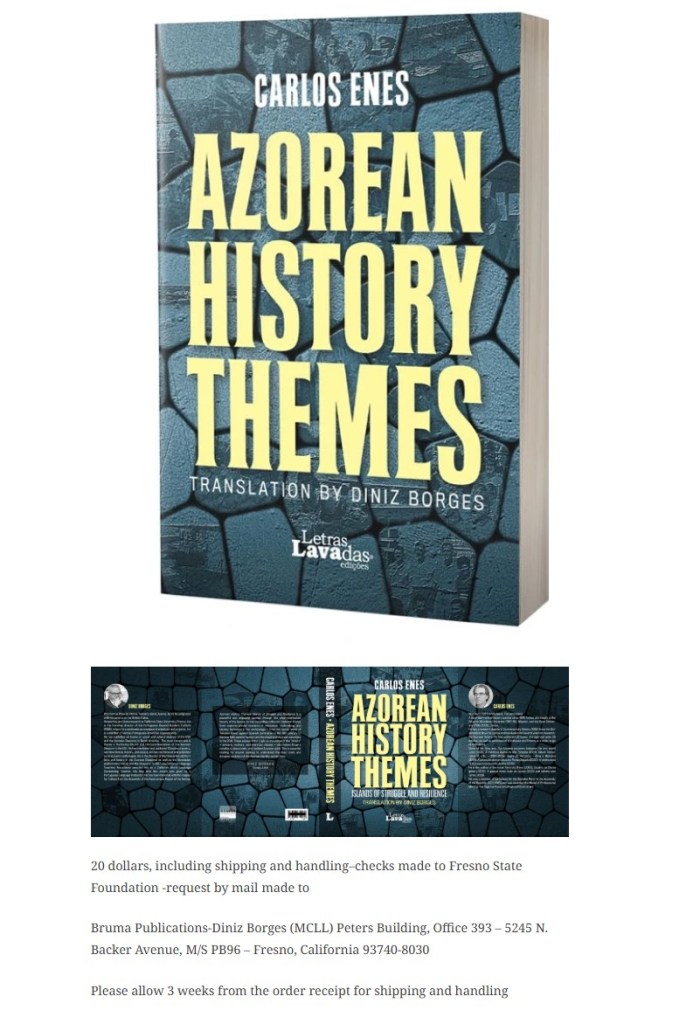

You can get the book here in the US and Canada by mail: