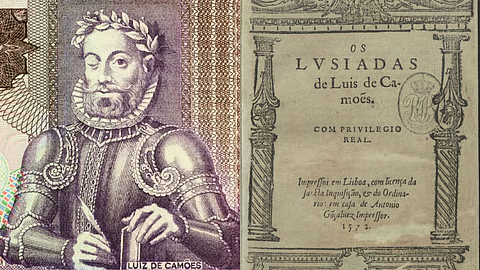

June 10 has long been celebrated as Portugal’s national day, known as Dia de Portugal, de Camões e das Comunidades Portuguesas. The occasion honors the death of Luís Vaz de Camões, the nation’s greatest poet, whose epic Os Lusíadas continues to inspire the Portuguese imagination and national identity. But the evolution of this day—from monarchy to republic, dictatorship to democracy—tells a story not only of shifting politics but of Portugal’s profound and ongoing transformation into a nation defined as much by its diaspora as by its territory. As we celebrate the legacy of Camões and Portugal’s unity, it is time to reconsider the name of this civic ritual and call it what it truly represents: Dia de Camões, Dia de Portugal e Dia da Diáspora Portuguesa.

The Making of a National Day

Portugal’s choice to center its national day around a poet, rather than a king, a battle, or a revolution, was both unique and deliberate. As Maria Isabel João details in her seminal article The Invention of the Dia de Portugal (2015), the process began in the 19th century. It culminated in the republican era, when Camões was enshrined as the personification of the Portuguese nation. His day, June 10, became not only a remembrance of literary greatness but also a projection of Portugal’s ideals: courage, endurance, exploration, and cultural depth.

In the early 20th century, the republican government sought to replace monarchist and religious holidays with civic ones. Camões, the secular “saint of the Republic,” was ideal for symbolizing a nation built on humanist and universalist values. As Guerra Junqueiro proclaimed in 1911, “Invocámos Camões para a libertar; moldemo-la então à sua imagem”—”We have invoked Camões to liberate it; let us mold it in his image”.

Camões and Empire: Ideology and Myth

Under the Estado Novo dictatorship, June 10 was reimagined as a nationalist and imperial holiday. In 1952, it became officially known as Dia de Portugal, and Camões was deployed ideologically to reinforce notions of racial unity and imperial destiny. His image as a soldier-poet who had served in Africa and Asia, and his epic that glorified the Portuguese navigators, became tools for legitimizing the regime’s colonial ambitions. Military parades, medal ceremonies, and youth festivals came to dominate the day, linking Camões to patriotic sacrifice and the myth of Portuguese exceptionalism.

This version of the holiday also presented Portugal as “uma raça que se distingue”—”a race that distinguishes itself,” a troubling echo of the regime’s rhetoric of racial hierarchy, even while promoting a vision of harmonious multiracial unity grounded in Lusotropicalism.

Democracy and Reinvention: From Nation to Communities

The Carnation Revolution of 1974 ushered in a new era of politics, accompanied by a reevaluation of national symbols. Although the initial post-revolution years were marked by instability, Camões Day continued to endure as a testament to its deep cultural resonance. In 1977, under President Ramalho Eanes, the day was officially redefined as the Dia de Camões e das Comunidades Portuguesas to acknowledge the vast Portuguese population living abroad.

This inclusion of the diaspora, first described narrowly as “communities,” was a turning point. It reflected a desire to reframe Portuguese identity in post-imperial terms. As Eanes declared in Guarda in 1977, “São os homens e não só os territórios que definem os povos”—“It is men and not territories that define peoples”.

By 1978, in response to concerns that the name “Portugal” had been erased, the day was given its current tripartite title: Dia de Portugal, de Camões e das Comunidades Portuguesas. This compromise sought to strike a balance between historical memory, poetic tradition, and modern democratic values.

Camões and the Plural Identity of Portugal

From the late 1970s through the 1980s, intellectuals and artists were invited to speak at the June 10 ceremonies, helping to shape a new, pluralistic vision of Portuguese identity. Jorge de Sena described Camões as “subversivo e revolucionário, em tudo um homem do nosso tempo”—a subversive and revolutionary Camões, profoundly relevant to modern Portugal.

The poet was no longer seen as merely the chronicler of empire but also as a symbol of exile, injustice, longing, and universalism—a reflection of the Portuguese emigrant experience. As Virgílio Ferreira eloquently put it, “Camões surge assim como o símbolo mais alto de uma reintegração dos presentes e dos ausentes, num destino comum, numa pátria comum”—“Camões thus emerges as the highest symbol of a reintegration of those present and those absent, in a common destiny, in a common fatherland”.

In this view, the poet—and through him, Portugal—is diasporic by nature: scattered, resilient, always searching for connection.

From Communities to Diaspora

The term “communities” (comunidades) was a diplomatic and administrative expression, but it fails to capture the full depth of what the global Portuguese population has become. “Communities” suggests isolated, static enclaves; diaspora conveys a dynamic, evolving, transnational existence marked by longing, reinvention, and cultural exchange.

As the historian Vitorino Magalhães Godinho noted, “Portugal é, antes de mais, um porto”—“Portugal is, first and foremost, a port,” a place of departure, encounter, and return. This metaphor speaks not only to the past of maritime exploration, but also to the lived experiences of millions of Portuguese around the world who maintain complex relationships with their homeland.

In this light, the celebration of June 10 should reflect the reality that Portugal is no longer merely a nation of historical empire or even a unified territory, but a living, breathing, global cultural body, deeply rooted in its diaspora.

A Call for Renaming

Therefore, it is time to revise the name of this holiday once again. The current title—Dia de Portugal, de Camões e das Comunidades Portuguesas—is a mouthful and falls short of reflecting the full spirit of what is being commemorated. A more accurate and meaningful designation would be:

Dia de Camões, Dia de Portugal e Dia da Diáspora Portuguesa.

This proposed renaming would:

- Acknowledge Camões not merely as a literary icon but as a transhistorical voice of displacement, universalism, and national longing;

- Affirm Portugal as a sovereign, democratic nation grounded in a shared cultural and historical legacy;

- Embrace the Portuguese diaspora as a defining element of national identity—not a marginal, but a central, aspect.

Such a change would signal to younger generations in New Jersey, Toronto, Paris, Luxembourg, and São Paulo that they are not peripheral “communities” but protagonists of the Portuguese story. As Eduardo Lourenço observed, Portugal is “uma imagem camoniana de nós mesmos”—“a Camonian image of ourselves,” shaped by both memory and imagination.

To reframe the day as Dia da Diáspora Portuguesa is not merely symbolic—it is a recognition that Portugal exists not just within its borders but in the hearts and contributions of its people around the world. It is a vision of a “new fatherland,” in the words of President Eanes, “constructed not on territory but on culture, solidarity, and a common future”.

Citation:

João, Maria Isabel. “The Invention of the Dia de Portugal.” Portuguese Studies, vol. 31, no. 1, 2015, pp. 64–83. Translated by Richard Correll. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5699/portstudies.31.1.0064.