Preface: Where Anyone Can Wear a Crown

On the island of Terceira, the wind carries more than salt and song—it carries centuries of faith, equality, and communal memory. The Festas do Divino Espírito Santo, rooted in medieval mysticism and shaped by the unique geography and soul of the Azores, have become one of the most powerful expressions of collective identity in the Atlantic world. This study examines the ritual and social fabric of these celebrations, with a particular focus on the empires, coronations, and Bodos that enliven the island’s parishes during the “time of the Holy Spirit.”

At the heart of these festivities lies a democratic spirituality: crowns not of gold but of shared bread, brotherhoods open to all, and functions where the sacred is served with soup and wine. These rituals, organized by mordomos, guided by promises, and sustained by devotion, unite generations across kitchen tables, processions, and prayers. Transmitted through both word and act, from parents to children, from emigrants returning home to new neighbors embracing old traditions, the cult of the Holy Spirit lives on—not only as a celebration of abundance and healing, but as a continual reaffirmation of belonging and hope.

This documentation brings together historical perspectives, anthropological insights, and local knowledge to honor a tradition that is at once ancient and evolving. It invites readers to step into a world where white flags flutter in volcanic winds, where every act of giving is sacred, and where community itself becomes the greatest miracle. Identification of the Manifestation.

Diniz Borges — PBBI, Fresno State.

We thank the Azorean government (the Department of Culture) for doing this work, which we publish below.

Designation: Festivals of the Holy Spirit: empires, coronations, and functions – Terceira Island

Domain: Social practices, rituals, and festive events

Category: Collective rituals

Social Context

Communities, groups, or individuals: In general, the ritual and festive practices of the cult of the Holy Spirit, which are still celebrated today on Terceira Island, involve practically all the communities that live here, insofar as they all have one or more empires or brotherhoods of the Holy Spirit, and these associations end up integratingthe entire resident population in their areas of influence, in almost all the activities and events they promote.

These brotherhoods, whose origins tend to be lost in time, appear to ensure the continuity of these festivities. The belief and devotion to the Holy Spirit, traditionally rooted in the ways of life, thinking, and acting of the people of Terceira, and of the Azoreans in general, must be an essential condition for someone to become a brother. This role is passed down from parents to children as a legacy, ensuring the renewal of brotherhoods—and now sisterhoods.

The brotherhoods, however, are associations with open membership, and there is almost always room for the integration of new members, such as those who settle in a particular community and wish to strengthen their ties with it through more active participation in its social and cultural events. Thus, at their origin, there are almost always the most basic ties and social relationships in which affection and closeness play a major role, defining circles of neighbors, belonging, and identification.

On the other hand, brotherhoods or empires may or may not be formal organizations, insofar as they are registered and have civil or religious (canonical) statutes. In the latter case, the statutes are covered by the Concordat signed between the Holy See and the Portuguese Republic, and the brothers are required to observe certain religious precepts, which were simplified in 1996.

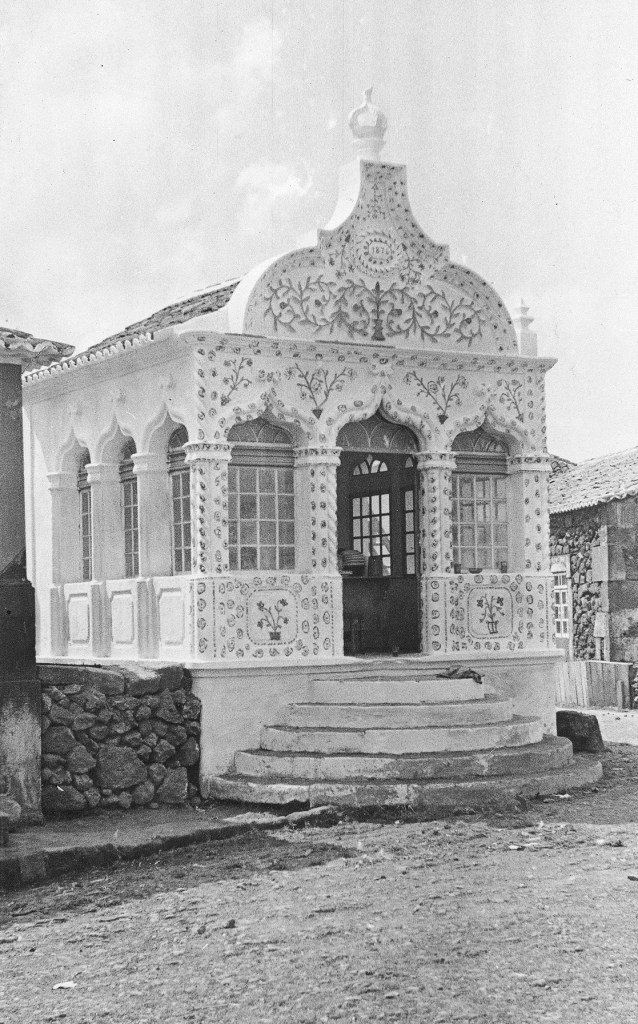

These associations, founded in various locations on the island, from the earliest times of settlement to more recent times, exist to ensure the annual celebration of the Feast of the Holy Spirit, through the observance of customs and statutes that define the main manifestations of worship and celebration, as well as the administration of their assets? triatos or impérios (buildings), pantries, empire crockery and other equipment essential for the functions (ceremonial meals) and the implements of worship (crowns, flags, sticks or torches) -, and the resources mobilized annually, i.e., the contributions of the brothers and other members of the community for the celebrations, which take place in the empires (buildings) on Pentecost Sunday and Trinity Sunday. These functions are ultimately carried out by a group of brothers appointed for this purpose and for a specific period, who may be referred to as mordomos, comissão, or mesa do império, and to whom, a few years ago, the figure of the procurador could be added.

Thus, the organization of the Bodos is a function of the brothers who are appointed members of the committee or stewards. However, it ultimately involves the participation of the wider community through the collection of contributions, which may be material, financial, or assistance in the preparations and performance of the various ritual and festive functions. All these interactions undoubtedly contribute to closer relationships and the recognition of the identity of each participant and the community as a whole.

Beyond this organizational structure, which seems to distinguish positions and create some hierarchy, the egalitarian character of the brotherhoods of the Holy Spirit prevails, with all brothers being eligible to perform coronations and/or functions, and thus play the role of emperor.

In most cases, the coronations and/or functions are promoted by brothers or community members who are selected in the previous year through a lottery. In this way, a brother can have a first Sunday or a Bodo Sunday. Nowadays, it is increasingly common for certain groups within the parish, such as youth groups or senior citizens’ groups, to participate in this lottery and celebrate a Sunday of the Holy Spirit. Only family members and friends of the emperor who are invited join in these celebrations.

In general, the celebrations of the Holy Spirit are justified both by the spiritual side of the belief in the divine power of the Third Person of the Holy Trinity, present in the miracle of healing and abundance, and by the experience of the values of equality and brotherhood, which are effectively embodied in mutual aid, sharing and giving, traditionally based on kinship and neighborhood circles, but which today seem to extend beyond the community and even the island, in an incessant search for a new order or empire, greatly facilitated by the development of the media and demographic mobility.

Territorial Context

Island(s): Terceira Island

Municipality(ies): Praia da Vitória, Angra do Heroísmo

Parish(es): All parishes in the municipalities of Praia da Vitória and Angra do Heroísmo

Temporal Context

Frequency: The Holy Spirit festivities take place annually in the spring and summer months, with the main festive period corresponding to the eight weeks between Easter Sunday and Trinity Sunday, which is sometimes referred to as the time of the Holy Spirit.

On the last two Sundays of this festive cycle—Pentecost Sunday and Trinity Sunday—the most significant festivities in terms of community participation take place, which are also generically referred to as bodos, domingos do bodo, primeiro bodo, and segundo bodo.

These festivities can extend to the preceding Saturdays and following Mondays, with celebrations marked by the preparation and sharing of food. In particular, the Monday of the first bodo, with the distribution of bread and wine from the bodo to all the houses that contributed to the festival, is of great importance in most of the island’s localities, which contributed to its choice as a regional holiday in the post-autonomy period, usually referred to as Holy Spirit Monday.

This calendar largely corresponds to the festive cycle of the Holy Spirit in rural parishes. In the urban and peripheral parishes of Angra do Heroísmo and Praia da Vitória, the festivities continue throughout the summer months, occurring in successive weeks.

Notably, there are also functions outside the usual time, occasioned by the payment of promises by people who live outside the island (such as emigrants).

Characterization of the Event

Characterization and History: Characterization:

The celebrations of the feast and worship of the Holy Spirit can be broadly characterized as a set of devotional and ceremonial practices based on the belief in the divine power of the Holy Spirit, organized around the use of this symbolism and the sharing of food, with the coronations or empires, functions, mordomias and bodos being its main ritual expressions and those that make up the festive cycle of the eight weeks or Sundays of the Holy Spirit.

These practices can be and are carried out according to varying programs in different locations and do not summarize all forms of devotion or worship of the Divine Holy Spirit. Devotees, whether or not they are members of the brotherhoods, may, for example, make and pay promises during difficult times in their lives. Promises involving cattle, sweet bread, and alfenim are particularly common. Votive offerings of this kind are given to the empires to be auctioned off in the camps on the days of the bodo. However, they can also be promises of alms, such as bread and/or meat, to be distributed directly by the payer of the pledge, typically after being blessed by the priest, in the presence of a symbol of the cult. Another type of promise may involve praying the rosary every night for a week, preferably in the presence of one or more symbols of the Holy Spirit, at home with family and friends.

Having a Holy Spirit Sunday, being crowned, or given a role during that period means participating in a lottery on the first Sunday of the previous year, called tirar o piloiro, which establishes the order in which brothers and sisters, whether committed by promises or not, will organize the celebrations in each of those eight weeks in the following year.

The ritual and festive sequence, which corresponds to each of these eight weeks, basically consists of preparing the house, setting up an altar to receive and display the cult objects—crowns, flags, and wands—and praying the rosary every night for a week, inviting family and friends to participate in this act of devotion. It can also mean taking the Holy Spirit to church and crowning, but not necessarily holding the empire (procession) and giving the function (dinner), which in the past only happened when there were very strong personal and social reasons, such as serious illness or mourning, but which nowadays is relatively common in some localities.

Although some changes have been introduced in recent decades, the organization of an empire or coronation, that is, the procession in which the cult objects are carried to the church, follows a traditionally defined pattern. The flags appear at the front and are followed by the crowns, both of which are flanked by sticks or torches. This procession forms at the emperor’s home and heads to the church, accompanied by or without a philharmonic band, depending on whether the parish has one or whether the emperor decides to hire one from outside. In the past, this musical accompaniment and certain ceremonial duties were performed by the foliões. In the church, at the end of Sunday Mass, the priest proceeds with the coronation while singing the hymn “Veni Creator Spiritus.” In some cases, the ritual ends with the departure of the coronation from the church and its arrival at the emperor’s house, from where the paraphernalia leaves for the home of the next emperor, carried by him or by his guests, depending on the custom of the parish, in a procession or by car, in a simplification of the ritual that is very common today. In others, the emperor continues his service with a function, that is, with a ceremonial meal of soups, stew, and beef, accompanied by homemade bread, table bread, and sweet bread, which was once prepared throughout the week.

The empire and the coronation are therefore the ceremonial moments of greatest social and symbolic importance, which tend to be preserved intact in their essence. This symbolic power is naturally based on the cyclical repetition of ritual norms and practices, as well as their material and aesthetic components. The norms establish not only the positions of the cult objects in the processions and at various moments of the ritual, but also the functions that guests are expected to perform. These guests are generally called employees, that is, those who should carry a flag, crown, or wear a crown. The material aspects, such as the ritual objects, equipment, ornamentation, and dress codes themselves. However, more subject to innovation imposed by fashion, they continue to respect the norm of white dresses for girls of Vereança and Coroa, ceremonial dresses for ladies, and suits for men, especially for the emperor, his family, and the other attendees at the função (the festivity).

In recent decades, the preparations and services for the function have been transferred from the emperor’s house to community spaces, such as kitchens and rooms in the Casas do Povo (People’s Houses). These changes are due to new ways of life, but also to regulations controlling food production, which have contributed to the disappearance of the festive ritual associated with the slaughter of cattle, which is consumed in this meal and in the distribution of meat as alms, which still takes place on the previous Saturday.

These were the calves of Thursdays. The decorated calves paraded through part of the parish and were also known as folias, constituting one of the most lively aspects of these celebrations, not least because they were linked to certain ornamental traditions – paper flowers – and musical traditions – the moda do pezinho, for example – and to the ritualization of the relationship with the animal to be sacrificed.

Although there are some variations, the distribution of meat and bread, which usually takes place on the Saturdays of the Domingos dos Bodos, continues to be carried out by the island’s brotherhoods, defining and preserving its meaning. In some areas, the brotherhoods only distribute bread and wine, while in others, meat is also distributed.

In urban areas, in addition to these distributions of alms, the Bodo celebrations usually include coronations. In the parishes of Ramo Grande, Lajes, and S. Brás, the Saturdays preceding these Sundays are celebrated with mordomias, which essentially involve organizing processions of offerings, including bread and sweet bread, distributed during the bodo. However, in the cases mentioned, these processions take on very elaborate ritual expressions. Similarly, during the same week, the transport of wine is celebrated with the decoration of carts with vegetables (faias) and flags, and the sharing of food on-site, usually in the beach and port area of the parish of Biscoitos.

As the função is the most important ceremonial meal, throughout the various moments of these festivities – changing of the crown, nights of praying the rosary, etc. – guests are treated to more or less light meals, in which pasta and wine traditionally predominated, and which today tend to be distinguished by a very diverse cuisine. Also noteworthy are the ceias de criadores (breeders’ suppers), a custom that is more urban than rural, linked to the need for cooperation between various farmers in raising livestock, which ends up creating ties between members of different and relatively distant communities, and which can be related to other forms of resource gathering.

Finally, it should be noted that the reality of these celebrations, with their numerous components and diverse locations on the island, is always more complex and diverse than a characterization of this kind can capture.

History:

According to oral tradition, the Holy Spirit festivals originated with the founding gesture of Queen Saint Isabel of Aragon, wife of King Dinis, who, in the 13th century, in the town of Alenquer, had a poor man crowned during mass and then offered a lavish dinner to the poor in the royal palace, which, having been imitated by the nobles of the court, gave rise to the tradition.

In more general terms, and according to various scholars, the introduction of the cult of the Holy Trinity and the empires in Portugal and other European countries is primarily due to the influence of Joachim of Fiore’s spiritualist ideology on medieval religiosity, a Calabrian Cistercian abbot. This ideology defended the arrival of new times, namely the time or empire of the Spirit, which inspired religious orders such as the Franciscans, who played a fundamental role in the settlement of the Azores islands.

These are therefore the spiritual, ritual, and festive manifestations that dominated the minds, practices, and customs at the time of Portuguese expansion, and with which the very project of forming and consolidating island societies developed in the 15th and 16th centuries and beyond.

The importance of such beliefs and celebrations is attested to by documentation, both about mainland Portugal and later about the islands, particularly about practices and customs considered excessive by the established powers (the king and the church).

In particular, concerning the deep roots of the cult of the Holy Spirit, authors tend to attribute the constraints of the island’s geography as the primary causes, including isolation and seismicity. In fact, this cult not only remained alive but was also taken by Azorean emigrants to new territories, becoming a fundamental component of their identity.

Associated manifestations: As mentioned above, the Holy Spirit festivities exhibit variations, and in this context, other cultural manifestations are associated and integrated, such as bodos de leite (milk weddings), touradas à corda (bullfighting with ropes), and singing, among others.

Transmission of the Manifestation

Status: Active

Modes: Oral combined with writing

Other modes: These beliefs and knowledge are primarily transmitted orally and consolidated through experiences throughout life, with various ritual functions accompanying the individual’s life cycle, from childhood to adulthood, integrating and creating contexts defined or supported by kinship and neighborhood networks. It is therefore within the family and neighborhood that the needs and meanings of devotion are internalized and strengthened. In cases where approved statutes exist, these often serve as formal mechanisms for ensuring their transmission.

Identification of Supporting Documentation

Bibliography: COSTA, Antonieta, 1999, O Poder e as Irmandades do Espírito Santo, Lisbon: Rei dos Livros

DURAND, Gilbert, 1984, “Iconographie e Symbolique du St. Esprit,” in Os Impérios do Espírito Santo e a Simbólica do Império. Proceedings of the II International Colloquium on Symbology, Angra do Heroísmo: IHIT, 37-53

LEAL, João, 1980, “The Feasts of the Holy Spirit on the Continent,” in Atlântida, Angra do Heroísmo: IAC, vol. XXV, no. 4, 23-35

LEAL, João, 1994, The Feasts of the Holy Spirit in the Azores. A Study of Social Anthropology, Lisbon: Dom Quixote

LIMA, Manuel C. Baptista de, 1984, “The introduction of the cult of the Holy Spirit in the Azores,” in The Empires of the Holy Spirit and the Symbolism of the Empire. Proceedings of the Second International Colloquium on Symbology. Angra do Heroísmo: IHIT, 123-167

MARTINS, Francisco Ernesto de Oliveira, 1983, In Praise of the Holy Spirit: Photographic Memories, [Angra do Heroísmo]: Regional Directorate for Cultural Affairs: Directorate of Emigration Services; [Lisbon]: National Press-Mint

MENDES, Helder Fonseca, 2006, From the Holy Spirit to the Trinity. A social program of inculturated Christianity, Porto: Portuguese Catholic University

MONTEIRO, Jacinto, 1983, “The invocation of the Holy Spirit in the seismic crises of the Azores,” in Problems of Reconstruction: earthquake of January 1, 1980. Proceedings of the VI Study Week of the Azorean Institute of Culture, Angra do Heroísmo: IAC, 427-450

PEREIRA, J. A., 1990, “On the Feasts of the Holy Spirit. Censorship and laws of the Diocesan Authority since 1560” in Bulletin of the Historical Institute of Terceira Island. Angra do Heroísmo: IHIT, vol. VIII, 58-63

Salvador, Mary L., 1984, “Simbolism and ephemeral art: an analysis of the aesthetic aspects of the festas do Divino Espírito Santo,” in Os Impérios do Espírito Santo e a Simbólica do Império. Proceedings of the Second International Colloquium on Symbology, Angra do Heroísmo: IHIT, 243-289

Periodical:

Tradição Popular. Single issue, commemorating the Festivities of the Holy Spirit. Angra do Heroísmo: Newspaper published by the Comissão do Império do Outeiro / Diário Insular, April 8, 1961