“Travelling, the Traveller and the Journey Theme in Azorean Literature”

By Dr. Carmen Ramos Villar, University of Sheffield

There is an underlying preoccupation in the literary production of the Azorean archipelago with emigration, and the ensuing search of an identity that incorporates the many realities emigration brings, which is not as prevalent in the rest of Portuguese literature. Azorean literature, a branch of Portuguese literature, explores themes such as the effects of emigration in a more extensive way than mainland Portuguese literature. In Azorean literature, emigration as a theme implies as journey, both mental and physical, which causes transformations in the character’s personality, their outlook, the way they view the world around them, their development as a person, and ultimately the way in which they define their identity (or identities).

We will begin by describing why emigration is such an important part of the Azorean cultural identity, examining the historical and literary factors that gave rise to the importance attached to it in Azorean literature. We will then move on to analyse how the Azorean novel depicts the theme of journey and the figure of the traveller, developing from the theme of emigration, as one of the marks of Azorean cultural identity.

Emigration forms part of what shapes Azorean cultural identity because of the social, economic and historical factors that shaped this society in the first place. The Azores played a key role in what can be defined as a key factor in Portuguese national identity; the expansionism era (also known as the period of discovery). The Azorean the archipelago participated actively in Portugal’s colonial enterprise from its beginning, either as recipients of emigration so as to populate the islands, as emigrants to other parts of the (Portuguese colonial) world, or as hosts to travellers. Due to their geographical position, the Azores quickly became instrumental for the sea voyages, providing bases and supplies, in terms of crew and material goods. The Azores’ strategic position in the Atlantic also became instrumental in the commercial system between Europe and the American continent, providing an obligatory stopover in the ocean crossing for both ships and aeroplanes. This has made for a society in some of the islands akin to a crossroad between places, where cultural interaction happens in a similar way to what James Clifford describes as the hotel in his hotel/motel analogy. Clifford categorises the experience of travel in a given society through the interaction and contact processes of different cultures which create a more cosmopolitan society, or shape and affect that society’s culture in a specific way.

The archipelago’s role due to the strategic position meant that there was a lot of contact with other cultures, as well as a way out of the islands in passing ships, either as replacement crew or as stowaways. The destination of Azorean emigration changed following world emigration patterns that began in the nineteenth century, reducing the number of people that went to the Portuguese colonies in favour of North America, the more popular destination. These migrants initially went as crew on board of whaling ships, establishing communities in New England, California, and Hawaii. The end of the nineteenth century also coincided with the rise of the nation state in Europe, which created an awareness of national identity in which people drew from language and history for its expression. The Azores, although isolated from Portugal due to their position in the Atlantic, still received contact from the outside world in the form of books and newspapers from the passing vessels. As European anthropologists explored the link between climate, geography and the individual’s character and identity at the turn of the twentieth century, Azorean intellectuals and writers also began to express an interest in identifying a specific Azorean cultural identity. Poets like Roberto de Mesquita (b. 1871, d. 1923) can be said to have been influenced by these ideas as, in his poems, he explored the effect of nature, climate and geographical surroundings, as well as the feelings of isolation and neglect, on the psyche. Mesquita has also been pinpointed as being the first literary and cultural representation of an Azorean cultural identity. However, Azorean critics such as Pedro da Silveira have argued that the cultural identity of the archipelago became sufficiently defined from that of Portugal since the beginning and, thus, not solely as a result of the processes of historical cultural contact.

The ideas about Azorean cultural identity can be seen as central in the generation of Azorean intellectuals and authors in the 1930s, who would add also the historical role of the islands and the effects of emigration to their definitions of Azorean cultural identity. These intellectuals, mainly educated in Coimbra, came into contact with the literary influences of Brazilian Modernism and Portuguese Neo-Realism, which would later be central in the formation of the Cape Verdean and Azorean literatures. It is important to highlight here the significant relationship and exchange of ideas between the Azorean and Cape Verdean writers and intellectuals of the 1940s which, in the case of the Azores, contributed directly to the formation and expression of a distinct Azorean regional cultural identity expressed through literature. This generation of Azorean writers became known as the Geração Gávea.

For this generation of Azorean writers, there is a preoccupation of highlighting a defined and differentiated Azorean cultural identity from that of mainland Portugal through literature. This differentiation is based on the depiction of the island environment, which can sometimes take the shape of using specific literary imagery, such as the feeling of confinement in the island, for instance, or of seeking to reproduce an approximation of the way Azoreans speak. Within the Azorean cultural identity proposed by these authors, one can also find the idea of Man being a product of a particular society, influenced by its environment and needing to break from its constraints. In so doing, the Azorean writers, like their Cape Verdean counterparts, used emigration as a theme so as to depict its effects in the Azorean society, and explore the sense of displacement in the individual’s construction of the self in the society around him/her.

The next generation of Azorean writers is situated in our period, and is headed by writers such as Onésimo Teotónio Almeida, Álamo Oliveira, or João de Melo, to cite a few. This generation builds up on the imagery and themes of the Geração Gávea generation and incorporates elements of Post-modernism in their depiction of what constitutes the Azorean character. The use of Post-modernism seeks to produce, through the text, alternative versions and perceptions of the world around us. In literature, this might translate itself through features like the fragmentation of the self within society, the idea of the self as fluid and subjective, and also the examination of what constitutes identity in a given setting. Azorean Post-modernism, in literature, looks at issues relative to the perceived cultural condition of being Azorean, such as the effect of migration, society, climate, or relationships with other characters and societies. In so doing, this generation of Azorean authors produce a dialogue with their Azorean counterparts in Portugal and in the Azorean emigrant community in North America. This creates a body of literature which is concerned with examining their perception of what it means to be “Azorean” in all the different contexts; in the archipelago, in mainland Portugal, and in the emigration setting of North America. In effect, the generation of Azorean writers create a web of writing where a symbiotic relationship between authors appears, enriching the literary search to portray Azorean cultural identity.

The theme of emigration, thus, is a constant preoccupation for the generations of Azorean writers who use the archipelago’s history to highlight their Azorean cultural specificity through literature. Emigration as a theme in Azorean literature is thus examined for its social impact on not only on those who leave, but also on those who remain in the islands. This theme explores the development of the islander and its dependency on social conventions and behaviour, which is also linked to the way the islander defines him/herself, or is defined by others. The result is the depiction of a personal journey that embodies the cultural manifestation of sociological and historical factors that a shape an emigrant society such as the Azores, and the emigration experience of its members.

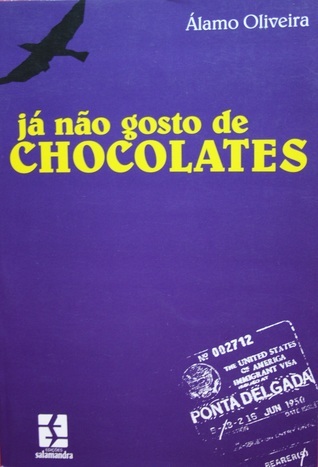

Álamo Oliveira’s novel, Já Não Gosto de Chocolates, centres around the decision taken by an Azorean family to emigrate to California in the 1950s. As the novel develops, we see not just the fragmentation of the main character’s self-perception following the decision to emigrate, but also that of his family’s perception of each other. In the novel, this is exemplified, for example, in how the characters’ names are changed after they emigrate, each shedding their Portuguese names in favour of adopting the American names in order to fit in and make sense of who they are in the new society. For instance, José Silva, the father of this family and the main character of the novel, becomes Joe Sylvia, Maria da Fátima, his wife, becomes Mary, and so on. In a sense, the idea presented in the novel is that of the confrontation of the fragmented self with an idealised idea of what that self should be in their new situation. Following on from this idea, the novel could also be seen as an exploration of coming to terms with a fragmentation borne out of a perceived loss on many levels after emigrating; loss of the familiar island environment and social customs in the new setting, loss of a island behaviour and moral code of conduct that is perceived to be better than that of the new setting, loss of a feeling of belonging in the island society, with its implied displacement in temporal and mental terms, and the perceived precariousness of belonging in the new society, and loss of the personal and family interactions with each other as they assimilate into the new society.

Reading the novel as an exploration of the many levels of fragmentation and loss undergone by the Azorean emigrant, José/Joe’s narration of the family’s story, weaving between the reminiscences of the past and his present, reads as an examination of his family’s adaptation to the new society which leads him in a growing state of powerlessness, where he convinces himself that his authority and position within his family was gradually stripped after emigrating. As he undergoes this examination, he analyses his attempts at preserving island customs and behaviour through exercising tight control on all the members of his family, thereby reducing the many levels of loss posed by the new culture. In so doing, however, he further contributes to the fragmentation process in the remaining family members, which he later concludes that it results as much from his own actions, as from what he sees as the corrupting effect of the new society.

Coming back to the way José/Joe narrates the family’s story, interweaving between the past and the present, we could also describe the novel’s construction as fragmented. As readers, we are accompanying the father of the family as he tells us the family’s story, contributing to the many interpretations of the theme of journey that can be derived from this novel; the family’s emigration story, the story of how each character changes and develops, the idea of the journey (cycle) of life ending with death, etc. However, it should be borne in mind that what we read is the account of one family member, José/Joe, who reminisces and analyses the past to make sense of the present. It is here that we can see the growing gap, the fragmentation, between the family members as a result of José/Joe being the only family member to have resisted full adaptation after emigrating. This resistance explains a disappointment at having found material wealth at the expense of having lost emotional wealth.

The story José/Joe tells us, supposedly gives each individual member of his family an equal opportunity to have their story heard, so as to analyse the effects of conflict and loss experienced after emigration from all the members of the family. Although an attempt is made to provide a forum for all the family member’s perspectives, no solution is found to the generational conflict – partly because all the family members have had their stories told on their behalf by José/Joe, who cannot, even at the end of the novel’s narrative, find a solution to this conflict. In this way, his account of his children’s acts of rebellion against paternal authority echo the powerlessness their father feels – because it is the father that tells the story and, thus, we see how José/Joe is placed, and placing himself, in a never-ending search for answers. The children’s perceived failure to mediate between the island customs and the demands for assimilation of the new society are seen as, in the father’s eyes, an inability to place their Azorean origins in an appropriate context of the emigration society. The way the family’s story is told through José/Joe’s perspective, thus, also accounts for the negativity surrounding the emigration experience for each member of the family. In José/Joe’s account, his negative perception of life after emigration colours how he sees his children’s lives. For him, the act of having emigrated is the logical explanation for the failed, or failing, relationships that each family member has with each other and also with their partners.

As each member is examined by José/Joe, it is interesting to note that the only relationships that seem to have worked, and stood the test of what the new society has supposedly thrown at them, are those who have a tenuous link to the island. In this way, José/Joe’s marriage to Mária de Fátima/Mary, and João/John’s homosexual relationship with Danny are seem as being successful because both father and son are searching for a island – which we increasingly perceive to be mythical – to act as a spiritual replacement of the island they have left behind after emigrating. For the rest of the family members, therefore, the inference is that they have somehow come under the negative influence of the new society. The new society, therefore, is seen as somehow corrupting; each child is seen to be either “punished” by death, illness, degradation in their relationships with others, and even an implied corruption to their personalities. The degradation has either come about because they have become “seduced” by the perceived materialism and superficiality of the new society, or because the new society interferes somehow with the individual’s relationship with the island, thus creating an internal spiritual conflict.

The only member of the family that cannot be seen to come under this category of having been “punished” or “corrupted” is the Down syndrome child that is the product of the marriage of António/Tony (the oldest son) and Milú (the dirt poor Azorean turned ambitious socialite in the U.S.). Far from the symbol of the degradation of the family relationships when faced with the perceived corrupting effects of the new society, this child could also be seen as the inheritor of the inability of the second generation to assimilate to the new values whilst still preserving the old island values, presenting this condition as a flaw or deformation on the innocent. The close relationship between the child and José/Joe is also a symbol of José/Joe‘s acceptance of his limitations and powerlessness to the change effected by the new society.

José/Joe’s death at the end of the novel is also presented as the acceptance of the events, and consequences, of the decisions that took place in life, and also as the beginning of yet another journey to another state of being. Thus, the conflict between island past/emigration present, the non-equation of the romance of the life of the emigrant and the non-romanticised reality of emigration, becomes the symbol of how the emigrant struggles constantly with various spatio-temporal changes that contribute to the construction of a self which incorporates these changes. The spatio-temporal changes come at a price; like the aforementioned name change when entering the US, or the act of shaving José/Joe’s moustache upon entering the nursing home, which takes away the last element of virility in his construction of self, and also constitutes the first of the final personal surrenders, and acceptance, that he has lost everything he had tried to preserve. The narrative’s play on the many levels of loss experienced by José/Joe and his family enables an examination of the losses experienced by the emigrant in the new society, losses which are caused by the decision to emigrate in the first place, and which begin a process whereby the emigrant is locked into a situation where, on return to the island, the emigrant feels as no longer fitting within the island environment because the island society encountered no longer matches up with the imagined island.

José/Joe’s narration, as it moves to and fro the past to the present in its search for reconciliation or unification between the fragmented self that has emerged since emigrating and the perceived and idealised island self that has been left behind, echoes the mental and physical dimension of the journey theme in Azorean literature. However, what we see is the observation and analysis of tiny pieces of a life, by an individual author who contributes to the construction of a whole, of Azorean cultural identity. Like a mosaic, the single events and episodes, the contributions of an author, like the individual pieces of the mosaic, are important to construct the whole picture. However, you only perceive the whole picture drawn by the individual pieces when you stand back and take it as a whole. In this way, emigration as a theme in Azorean literature, thus, forms a backdrop in which the social drama of this historical and social fact is explored in order for the author to show how the experience of it shapes the Azorean islander’s sense of self, and how this sense of self contributes to the construction of the mosaic of Azorean cultural identity.

* * *

Text revised 2009 by Carmen Ramos Villar from her paper presented 9-12 May 2001. Originally published in Actas do IV Congresso Internacional da Associação Portuguesa de Literatura Comparada, Estudos Literários/Estudos Culturais, Vol. I: “Relações Intraliterárias, Contextos Culturais e Estudos Pós-Coloniais.” University of Évora, Portugal.