Echoes of the Carnation Revolution from Portugal to the Portuguese Diaspora in America

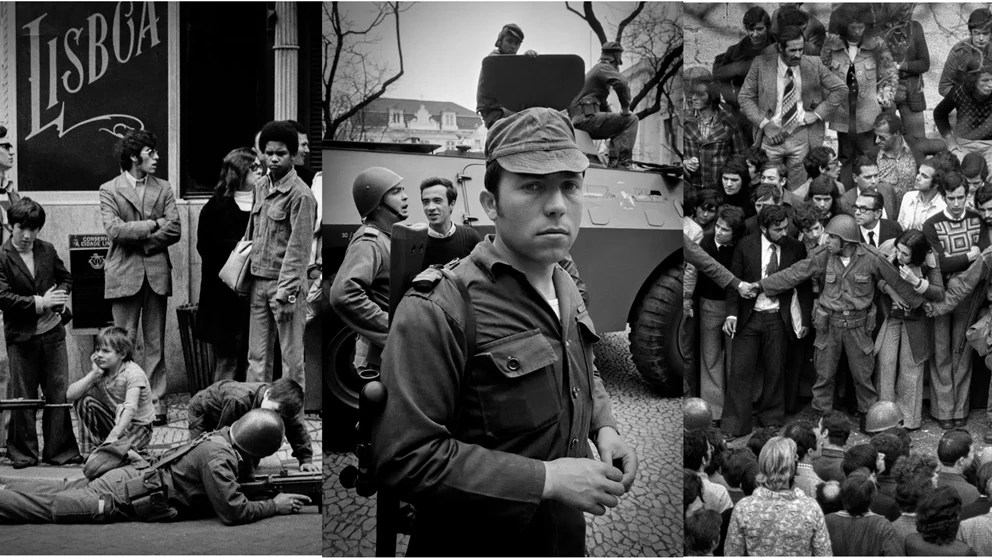

On the morning of April 25, 1974, tanks rolled into Lisbon. But instead of bloodshed, there were flowers—red carnations tucked into rifle barrels, handed out, accidentally, one might say, by Celeste Caeiro, embraced by soldiers, and waved by jubilant civilians. As it came to be known, the Carnation Revolution overthrew nearly five decades of dictatorship under the Estado Novo regime. It was a revolution unlike most others: almost bloodless, deeply poetic, and profoundly transformative for Portugal. And for Portuguese people abroad—particularly in the United States—it was a moment of pride, rediscovered identity, and, certainly, a renewed hope.

The significance of April 25 extends beyond Portugal’s borders. It changed not only the nation’s political trajectory but also touched the lives of the Portuguese diaspora, reinvigorating a sense of connection to a homeland that had, for many, long been a place of silence, fear, or nostalgia. I remember vividly watching the news of the revolution with my family, huddled around the TV set in rural California, as Walter Cronkite reported on the unexpected toppling of a dictatorship in a country barely mentioned in my American history books. My father, who had left Portugal in search of a better life, stood quietly with tears in his eyes. “Finalmente,” he whispered. Finally! Finally, Portugal was reborn, and we, though oceans away, felt the tremor of hope.

Flowers, Freedom, and Poets

Political elites or foreign interventions did not lead the revolution. It was organized by the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), a group of young officers (mostly captains) frustrated with the never-ending colonial wars in Africa, the rigid censorship of the press, and the oppressive climate of fear that had governed daily life. Among these officers, one man stood out: Salgueiro Maia, who became a symbol of moral clarity and courage. As he led his troops into Lisbon, he famously told them: “If we are to die, let it be for something worthwhile.” He later added, “There are those who want power. I want a clean conscience.” Maia’s words remain etched in the Portuguese collective memory, a reminder that revolutions, at their best, are acts of conscience.

The Portuguese people joined the military in droves, not with weapons, but with music, poetry, and red carnations. The moment was so charged with symbolism that it seemed to be taken from the verses of a poem. Indeed, poetry was not only part of the revolution, but it was also its soul. Manuel Alegre, whose poems were once censored and circulated in whispers, wrote in As Naus:

“Era o tempo das palavras interditas / e das sílabas escondidas no vento.”

It was the time of forbidden words / and syllables hidden in the wind.

His lines capture the breathless atmosphere of the dictatorship, when expressing one’s thoughts freely was a risk. But on April 25, the syllables returned—no longer hidden but shouted in the streets. Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, known for her lyrical clarity and moral intensity, celebrated freedom with crystalline simplicity. In her poem 25 de Abril, she wrote:

“Esta é a madrugada que eu esperava / o dia inicial inteiro e limpo.”

This is the dawn I was waiting for / the inaugural day whole and clean.

It was a new beginning, unburdened by the lies and cruelty of the past. Her words evoke the collective relief of a nation that has been holding its breath for too long. José Carlos Ary dos Santos, revolutionary bard and political poet, gave the people a voice in his stirring lines:

“Portugal ressuscitado, / embora com voz cansada / tem o seu povo acordado.”

Portugal has risen, / though with a tired voice, / and its people are awakened.

Ary dos Santos spoke directly about people’s fatigue and resilience. The revolution was not a coup by the elite. It was the awakening of a people who, even in exhaustion, found the strength to rise.

The revolution has been the subject of intense academic study, most notably by historian Raquel Varela, who has emphasized the radical democratic spirit of the days that followed April 25. In her book A História do Povo na Revolução Portuguesa, Varela argues that “the revolution did not end on the 25th of April; it began there.” She describes how workers took over factories, communities formed popular assemblies, and for a brief, heady period, Portugal experimented with direct democracy. As she writes: “Foi o mais belo momento da história portuguesa contemporânea.”

It was one of the most beautiful moments in contemporary Portuguese history.

Varela’s work reminds us that the revolution was more than an event—it was a process. It left behind a legacy of courage, participatory democracy, and the belief that ordinary people can transform history.

Portugal Seen from Afar: The Diaspora’s Revolution

The revolution was a joyous shock for those of us in the Portuguese-American diaspora. In U.S. schools, Portugal is rarely mentioned. If it was, it was usually in the context of a backward nation ruled by an aging dictator and disconnected from the world. But in 1974, everything changed. Suddenly, Portugal was on the front page of The New York Times, featured on CBS Evening News, and spoken of with admiration.

I remember the glow on my father’s face as he watched the revolution unfold on our small screen in our small, humble home in the dairy farm where my dad and I worked (I was 15 years old). That day, Portugal was not an afterthought—it was a beacon. For my family and for so many others who had emigrated because of poverty, war, or repression, April 25 was a homecoming of the spirit. It connected us to the possibility of a Portugal we had long dreamed of but never thought we would see. It gave us hope that we could return—not necessarily physically, but emotionally and culturally—to a homeland reborn in freedom.

Yet, despite this profound moment in our collective history, it is disappointing that so few Portuguese-American organizations commemorate April 25. There are ample celebrations of religious festivals, fundraising dinners (some of which are just for fundraising and not Portuguese culinary events, as they should be), and folkloric events. Still, the date that marks Portugal’s liberation is too often forgotten. That absence is troubling. For a diaspora that values identity, heritage, and connection, failing to celebrate one of the most important moments in modern Portuguese history is a missed opportunity.

The Carnation Revolution is not only Portugal’s—it is ours, too. It should be taught, remembered, and honored in Portuguese schools in the United States, cultural centers, and community newsletters. It is a story of who we are.

Challenges and Opportunities

Today, Portugal faces new challenges—economic uncertainty, housing crises, climate vulnerability, and the ongoing pressure of globalization. But it also stands as a model of democratic resilience. It weathered the post-revolutionary turbulence and built a functioning, pluralistic society. The European Union, to which Portugal joined in 1986, has helped modernize infrastructure and deepen democratic practices, although it has also brought economic constraints.

In the U.S., the Portuguese community also needs to evolve. The early waves of immigrants from the Azores and Madeira gave way to new generations who may not speak Portuguese fluently or feel a strong connection to their ancestors’ land and culture. But they can be reconnected through literature, music, history, and, above all, through stories like April 25.

We must make space in our community organizations for youth engagement, historical memory, and the recognition that identity is not static but a bridge between the past and the future. Translating poetry, preserving oral histories, and organizing civic events tied to democratic values are all ways we can honor the spirit of April 25.

As Salgueiro Maia once reminded us, it’s not about seeking power, but having a clean conscience. The revolution’s legacy is not in monuments, but in memory—and in what we do with that memory.

The Carnation Revolution was a uniquely Portuguese miracle—bloodless (or almost so, as the PIDE, the secret political police, did fire on people in the streets), musical, poetic, and transformative. It gave Portugal back to its people and inspired those of us abroad to look at our homeland with renewed pride. I will never forget watching the news that night in 1974, how my father stood a little taller, and how my schoolmates asked me about Portugal for the first time. It was as if we had all been waiting for the same dawn that Sophia de Mello Breyner wrote about—the inaugural day, whole and clean.

Let us not forget that day. Let us teach it, celebrate it, and pass it on. Because April 25 does not belong only to the past. It belongs to all who believe in the power of peaceful change, of poetry and courage, and of a people who, when asked for silence, answered with a song, flowers, and hope.