Diogo Ourique’s Let Me Out of This Book is a brilliant metafictional novel that ruptures the boundaries between author and character, narrative and narration, fiction and life. It is a self-aware literary journey that explores the power struggle between a character—Daniel Rebelo—and his author in a battle for narrative control and existential significance. In the age of digital saturation and diminishing attention spans, Ourique’s work offers a spirited defense of literature as both a playground and a battleground, arguing that fiction, far from being escapist, is a crucible for philosophical inquiry and creative emancipation.

At the novel’s heart is Daniel Rebelo, a character who becomes aware that he is nothing more than an author’s imagination. This revelation sets in motion a thrilling, absurd, and often poignant quest to wrest control of his story from his creator. “Yes, Daniel finally knew he was a fictional character! He didn’t exist in the real world. He was probably the figment of at least one person’s imagination: the one who writes and describes his life.” Daniel’s awakening mirrors a kind of literary gnosticism, a fall from false innocence into the painful light of truth.

The book’s central conceit draws on a rich tradition of metafiction, echoing the narrative disruptions of Luigi Pirandello’s Six Characters in Search of an Author, the ontological crises of Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler, and the existential flair of Charlie Kaufman’s Synecdoche, New York. But Let Me Out of This Book goes a step further. Daniel doesn’t merely speak to his author—he rebels. “If we both exist in different universes, why do you get to be the dominant male?” he challenges. “Why do you have to be the one in control?”. This philosophical and political question asks who has the right to shape reality—creator or creation?

This tug-of-war is dramatized with satirical verve and philosophical rigor. Daniel accuses his author of a god complex: “You’re not a god, and you’ll never be one! Not even in the story you made up yourself”. His desire for autonomy is a rejection of literary convention and a cry for ontological freedom. Daniel wants what all humans wish to: meaning, coherence, and authorship of his life. But he must wrestle with the possibility that his life—his memories, desires, even his rebellions—might be scripted.

The novel is also deeply intertextual, drawing on the myths and metaphors of Western literature. When Daniel shouts, “I wouldn’t be the first creation to turn against its creator,” he joins a long line of literary and cinematic rebels, from Frankenstein’s monster to HAL 9000. His rebellion is fueled by the belief that ideas can take on their own life. As he says, “Zorro, James Bond, Dracula, Moby Dick… All these characters materialized in some way… even those that didn’t leave the paper have also materialized if people remember them”. Fiction, then, is a vehicle for immortality but also for defiance. Indeed, we have dreams, doubles, and the character’s revolt in a metafictional world.

One of the novel’s most striking sequences is Daniel’s foray into authorial imagination, where he tests his newfound power by conjuring different literary genres. He imagines a city transformed by absurdity—a singing window, alien invasions, a pig running through the streets—thereby ticking off genres like fantasy, science fiction, crime, and comedy. This scene is not a mere parody but a metafictional flexing of literary muscles. Daniel is learning to write, imagine, and create. He becomes character and co-author, a duality destabilizing traditional storytelling hierarchies—the absurd logic of fictional lives and the characters wanting to be let out.

This battle for narrative dominance reaches a climax when Daniel attempts to write his own story on a typewriter, only for the pages to catch fire in a spontaneous sabotage from the author. “You know this is pointless. You’re only wasting your energy, Dani. Leave the writing to the experts,” the author writes in a sarcastic footnote. But Daniel persists, even as the manuscript burns—a metaphor for the fragility and tenacity of creative will. The illusion of freedom, the mirror of fiction, and the character who knew he was written.

The novel’s thematic core is its meditation on the nature of existence—fictional and otherwise. What does it mean to be real? Daniel’s search for authenticity leads him to reject the synthetic comfort of the story written for him. “I prefer risking not living at all than continuing to exist with the knowledge that I’m a lie,” he declares. Yet, the novel is honest enough to suggest that all lives, real or fictional, are in some sense constructed. Memory is selective. Identity is mutable. Even the author must admit that imagination “has a life of its own”.

This uncertainty reaches a crescendo in a scene where Daniel confronts the blank page—the infamous writer’s block. He finds himself in a literal and figurative void, suspecting that his author has paused the story because he doesn’t know what to do next. “Maybe that was the famous blank page syndrome,” Daniel muses, “the tragedy of creative block”. That a character could recognize the limitations of his creator speaks to Ourique’s radical vision: a literature where characters are not vessels for authorial intent but beings with their consciousness, longings, and agency.

This literary rebellion is not without cost. Daniel’s journey is marked by violence, loneliness, and existential despair. In one of the novel’s darker turns, he murders characters who may or may not be figments of his imagination. He even attempts suicide. But even this is reframed as a creative act to reboot the story on his terms. He imagines a safety net under the bridge, and thus, it appears. “They were working together to continue that story,” the narrator says, hinting at a possible reconciliation between author and character. Yet, reconciliation remains elusive. Daniel never fully cedes control, and the novel ends with a sense of uneasy coexistence between creator and creation. The author, reflecting on whether to publish the story, worries that it might invite more characters to become self-aware: “I fear for the sanity of literature itself if that happens”. Daniel, of course, disagrees. For him, literature’s vitality lies in its ability to surprise, challenge, and subvert.

In a time when literature often competes with more immediate forms of storytelling, Let Me Out of This Book reminds us of the unique power of the written word. The novel talks back to itself, questions its existence, and dares to imagine characters as more than puppets. With wit, insight, and audacity, Diogo Ourique crafts an intellectually invigorating and emotionally resonant story. It is not merely a written story; it is a story about being—what it means to be made and what it means to unmake oneself. As Daniel puts it, in a moment of clarity that encapsulates the novel’s spirit: “This isn’t your story anymore, my friend. It stopped being yours the moment I had to save your ass by myself… It’s our story now! And soon it’ll be just mine”.

In the end, Let Me Out of This Book is both an ode to and an interrogation of storytelling. It is about the perils of omnipotence, the rebellion of the imagined, and the beautiful, terrifying possibility that characters may one day write themselves.

Diniz Borges, California

Author Diogo Ourique

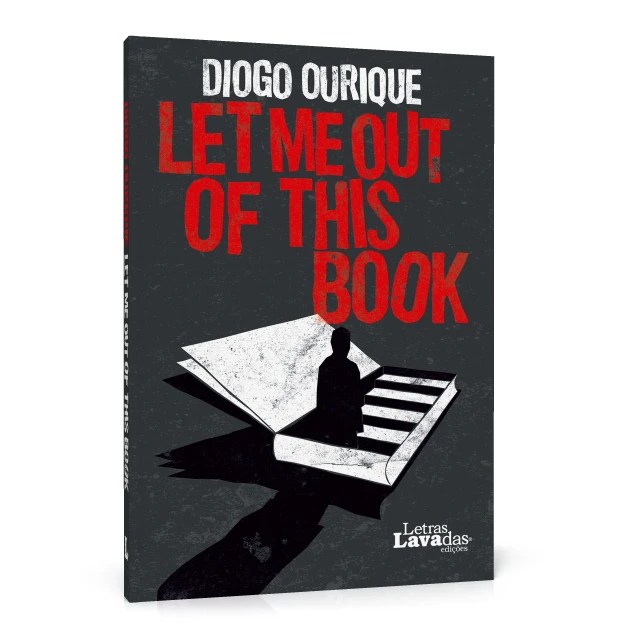

The book is available in English through Bruma Publications in the US and Canada and through Letras Lavadas in the Azores, all of Portugal, and the European Union.

https://www.letraslavadas.pt/let-me-out-of-this-book/

https://www.letraslavadas.pt/tirem-me-deste-livro-diogo-ourique/