In Inner Snow, poet Alberto Pereira offers readers a rare fusion of fierce social critique and lyrical transcendence. This volume not only brings to light one of Portugal’s most original poetic voices but also opens an accessible and compelling gateway for second and third-generation Portuguese-Americans and Portuguese-Canadians to engage with the power of modern Portuguese literature. The book, which draws from three of Pereira’s prior collections—Poems with Alzheimer’s, Journey to the Birds’ Dementia, and As in an Internal Shipwreck We Die—gathers forty compact, blazing segments that inhabit a space of poetic urgency, exploring themes of identity, alienation, madness, love, exile, memory, and the collapsing weight of modern life.

Pereira’s voice is unrelenting from the first poem and emerges from a profound sensitivity. “I pay into the social insecurity, / not to be entitled to blood,” he writes. In a few lines, he fuses bureaucratic critique with existential despair. The poet walks through city streets where “prophets erected chapels / to climb the poppies,” and where “coins in their hands / bought angels they put in syringes.” These surreal but deeply grounded images reflect a society addicted to false paradises, corrupted by capitalism, and numbed by despair. In the translation, I tried, ardently, to maintain the taut, aphoristic rhythm and somber musicality of the original, providing Anglophone readers with a resonant experience that does not feel secondhand. For younger generations raised in English-speaking countries, this access to powerful, contemporary voices from the Lusophone world bridges a crucial cultural and linguistic gap.

At the heart of Inner Snow is the motif of rupture—between body and spirit, past and present, homeland and exile. Pereira’s images are often violent in their beauty: “A tumor walks a man,” he writes in poem 3, “The river is the house where the blood lives.” Here, illness and the disintegration of the body become metaphors for a broader social and spiritual collapse. And yet, even in these darkest places, his language seeks transcendence. “The garden glow seems to have gotten drunk,” he observes, as if nature is mourning or madness. For diaspora readers, especially the descendants of immigrants who left Portugal or the Azores for North America, these poems speak directly to the inherited trauma of displacement. Pereira’s landscapes are neither purely physical nor metaphorical; they are felt, endured, and bled into.

The political thrust of the collection is unmissable. Pereira doesn’t name injustices with simple slogans; he renders them in searing allegories. In poem 1, when he is offered a job by a boss who says, “I’ll pay you if you produce sunshine / and we declare shipwrecks,” the poet refuses, “I became an island.” This transformation is key—where others are subsumed by the machinery of profit and exploitation, Pereira imagines himself as an isolated entity, perhaps alone, but with integrity. In poem 28, the poet flatly writes: “Capitalism, / requiem of the harps / that the people want to sow.” These are not distant, abstract meditations. They are personal, embodied reckonings with a world that increasingly marginalizes the sensitive and the poetic. For the children and grandchildren of immigrants who sacrificed poetry for survival, this confrontation with economic and moral systems feels both familiar and deeply necessary.

The poems also delve into personal terrain with startling intimacy and originality. Love is never idealized. In poem 5, Pereira writes, “Never say love / without knowing that worms / are born in the hangover of paradise.” Love is a wound, a memory, an echo. The erotic is not separate from decay—it is part of it. In poem 10, he confesses: “I still wanted you when the gunpowder / played its last chords on the branches.” These poems do not romanticize the past but instead document its disintegration. Still, they never give up the shadow of beauty. The emotional rawness of these reflections will resonate with diaspora readers raised with complex cultural inheritances—where longing is intergenerational, and identity is defined as much by absence as by presence.

Nostalgia plays a curious role in Inner Snow. Pereira evokes childhood with a painter’s palette—referencing not just personal memory, but an entire aesthetic lineage. Poem 24 recalls “the landscapes / that recited the brushes / of Monet, Renoir, Sisley and Degas.” Childhood becomes a site of artistic and sensory plenitude, quickly followed by disillusionment. In poem 19, he invokes “mothers, / and between the thighs / the great window to the linden trees,” before observing the descent into patriarchy and domestic erasure. The reverence Pereira offers to mothers—figures who are repeatedly described as carrying silence, resilience, and transcendence—feels like a poetic restoration. This reclaiming of maternal divinity offers emotional affirmation and cultural recognition for diaspora communities, often defined by matriarchal strength.

One of the most powerful aspects of Inner Snow is Pereira’s relationship with language itself. “The poem regurgitates / wounds as high as buildings,” he writes in poem 5. Elsewhere, in poem 4: “The thought learns to be a boa constrictor.” Language is violent, shifting, and full of contradiction. It is both the site of salvation and the very field of suffering. This dual relationship with words makes translation so important. To capture Pereira’s syntax—sometimes surreal, sometimes aphoristic, always charged with tension- required many hours of reflection and a deep poetic empathy. I hope that the English version gives these sublime poems a life of their own while remaining loyal to the disruptive beauty of the original. For young Portuguese-Americans and Portuguese-Canadians, often raised at a remove from literary Portuguese, this translation becomes an act of cultural reconnection.

Another layer that makes Inner Snow significant for these readers is its portrayal of madness—not as a trope, but as a state of consciousness born of clarity. Pereira often writes from the perspective of the madman, the fool, the outcast. “The sun used to have propellers / tearing the locomotion of the precipices,” he says in poem 7. Childhood innocence, once incandescent, becomes fragmented. “We strayed from the insurrection of childhood,” he laments. But it is precisely in this marginal perspective that truth appears. “It is always the madmen who put the sandals on the anthem,” he declares in poem 27, one of the collection’s many political and poetic fusion moments. This madness is not a failure; it is the ultimate vision. For readers born into hybrid identities, negotiating between inherited traditions and modern realities, Pereira’s position at the margins speaks volumes. He is not merely writing about Portugal or personal pain; he is mapping a borderless, inner geography that diaspora readers will recognize as their own.

The book’s title, Inner Snow, encapsulates its paradoxical power: the cold fire of introspection, the white silence that can burn. “Love always has the accent of snow,” Pereira writes. And indeed, love, like poetry, like homeland, is never pure in this collection—it is always tinged with death, memory, and rupture. And yet, it is exactly this tension that gives poetry its vitality. These are not poems of resignation; they are acts of resistance in their most fundamental sense. Resistance against numbness, against commodification, against forgetting.

For the descendants of the Portuguese diaspora, many of whom navigate a world of dual loyalties, shifting languages, and fractured memories, Inner Snow offers a reading experience and an invitation. An invitation to enter the contemporary world of Portuguese poetry, not as outsiders, but as rightful inheritors. It is a work that shows them that poetry is not just in the past, not just in the saudade of fado or the ruins of empire, but in the now—urgent, raw, and alive.

Alberto Pereira’s poems, which I had the honor to translate, do more than cross linguistic boundaries; they extend a hand across generations. They say, with fire and ice: your language is here, your pain is valid, your beauty is real. Perhaps most importantly, they remind us that the poem still has the power to be a home in the chaos of exile and inheritance.

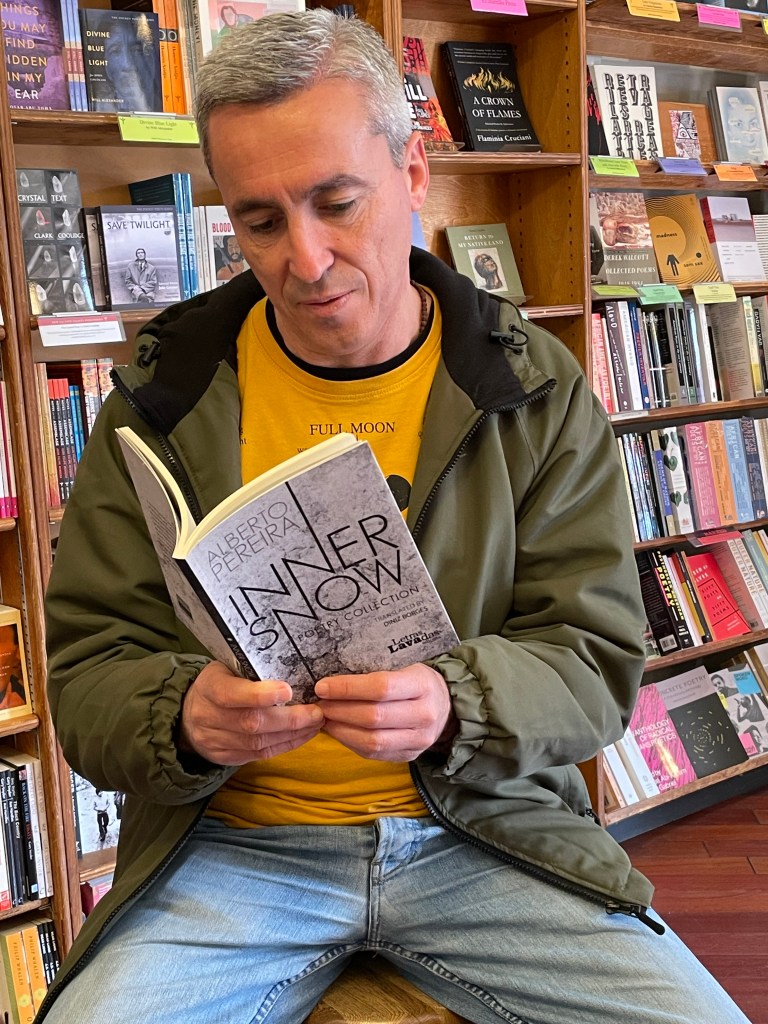

Diniz Borges, translator

You can purchase the book in the US and Canada through Bruma Publications.

You can order it through our partner, Letras Lavadas, in the Azores, Madeira, mainland Portugal, and throughout the European Union.

https://www.letraslavadas.pt/inner-snow/