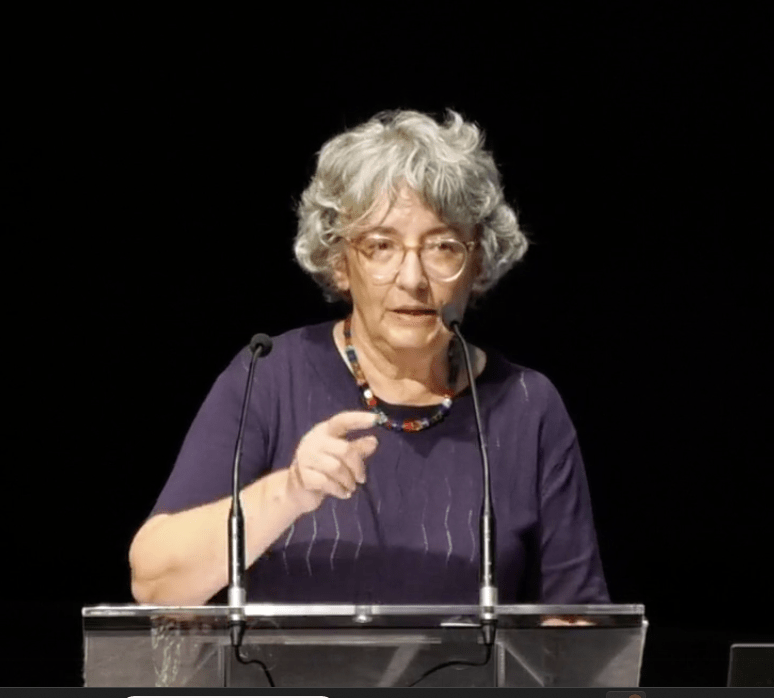

On March 26, Portuguese Book Day was established on the initiative of the Portuguese Society of Authors, evoking the date on which the first book was printed in Portugal – the “Pentateuch” (Faro, 1487). To celebrate this ephemeris, we spoke to Professor Maria do Céu Fraga, a Classical Portuguese Literature and Camões researcher specialist, about the value of the classics, the training of new readers, and the centrality of reading in developing sensitivity and critical thinking. “Schools can’t give up on books and, from the earliest years, they have to value the written text in itself,” she says.

Correio dos Açores – How important is it to mark Portuguese Book Day?

Maria do Céu Fraga (Professor at the University of the Azores) – Like any “day” dedicated to a theme, Portuguese Book Day seeks to draw attention to a subject, make it the subject of analysis and discussion and give it a prominence in social life that matches the importance that the promoters of the celebration feel is not recognized by the community.

If the Portuguese Society of Authors has chosen to promote this celebration the day on which, in the distant years of 1487, the notebooks of the first book printed in Portugal, the ‘Pentateuch’, came off the press, celebrating the Portuguese book will therefore mean underlining the importance of books and, consequently, of writers and the worlds they create. On a loose note, it should be remembered that the Pentateuch was printed in Hebrew and that the ‘Constitutions made by Dom Diogo de Sousa, Bishop of Porto’ was the first to be printed in Portuguese.

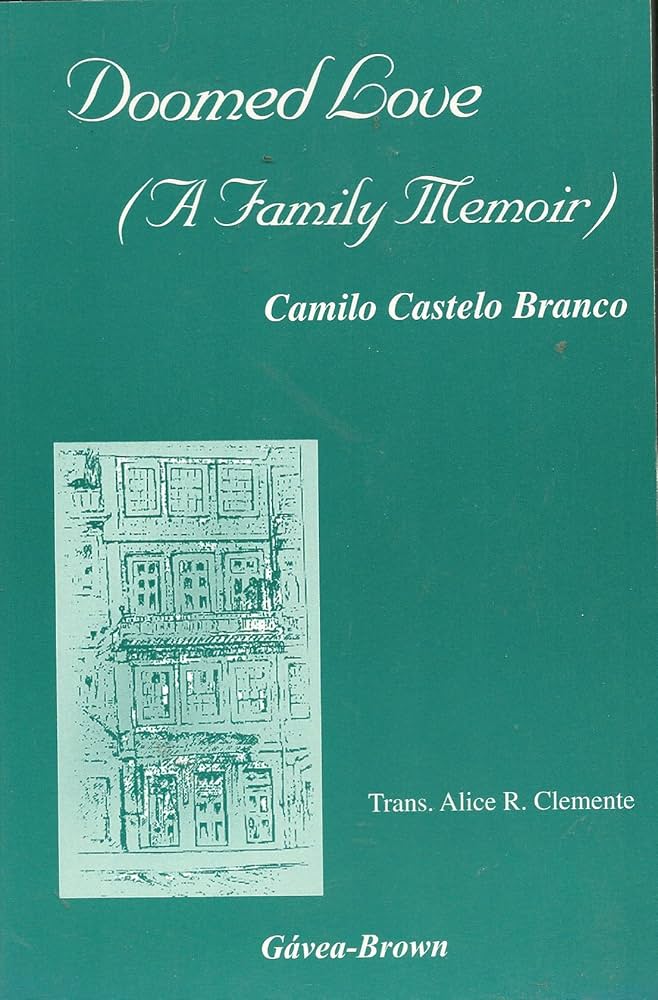

How can ephemera such as the 500th anniversary of Camões or the bicentennial of Camilo Castelo Branco’s birth renew interest in the classics and stimulate a new reading of the Portuguese literary tradition?

Both Luís de Camões and Camilo Castelo Branco were authors who didn’t shy away from uncomfortable topics, whether from a political and social point of view or an individual point of view.

The literary canon, i.e. the set of texts that we consider to be irreplaceable heritage, changes its boundaries over time, incorporates new authors and, although it doesn’t reject them, forgets others that it may take up later.

Readers sometimes tend to look for books that respond immediately to their needs, which can be the most varied, from thinking about a social problem to having a good laugh, getting emotional, learning about the world, or simply reading a text that is aesthetically well done in elegant Portuguese.

Celebrating 500 years since the birth of Camões, or 200 years since that of Camilo, although one takes us back to the 16th century and the other to the 19th, has the same meaning: it’s about highlighting their integration into our common life, it’s about recognizing and seeking to deepen our debt to them.

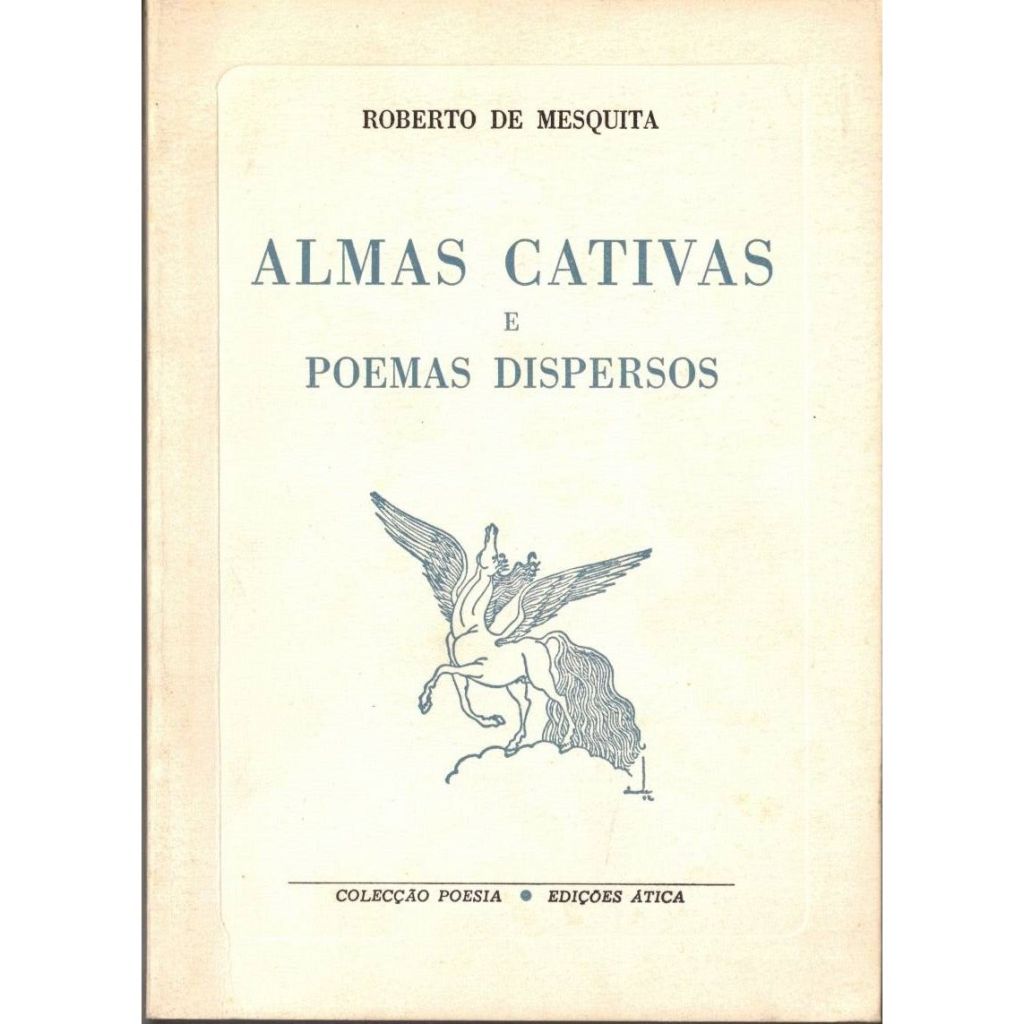

Which Azorean authors do you consider essential reading? What works would you highlight on this day?

I’ll tell you just one poet: Roberto de Mesquita. For his rightful place in the history of Portuguese literature, and for the meaning he takes on, always oscillating between the general, universal sense, and the mirror of the islander, historically situated. He is, of course, an author who may seem “difficult” – as life is sometimes difficult – but who is worth investing in, for the world that this poet opens up to us, isolated in Flores but awake to the universal.

How are new readers formed today? What role should the school and the community play in this process?

The question is very interesting because it shows us the contradiction between the school’s objectives and the reality we are faced with—that is, between society’s dreams for the next generation, on the one hand, and the present reality, on the other.

Schools should form communities with intellectual interests, including a love of reading – and literary education is part of official programs. But the school cannot be alone. In other words, if a child or young person sees that their teachers tell them to read, but they don’t, and they don’t find active encouragement from the adult society around them, the school can do little.

There’s a book by Daniel Pennac that has been around for a long time and which, I think, is still very relevant in this respect. It was translated under the title ‘Like a novel’ in Portugal. In its pages, the author, himself a teacher and novelist, insists on the value of reading as a pretext for personal affirmation, for the acquisition of a maturity that will require the effort that literary reading necessarily implies.

The school must not give up on the book. From the earliest years, it must value the written text as a thoughtful and careful message that is transmitted and allows each reader to interpret the world and themselves, relating to others. At the same time, schools cannot dissociate literature from language teaching; otherwise, one field will be impoverished.

And what is the role of universities in training readers?

In this regard, I believe that universities should pay close attention to literature and books, considering them to be their allies in the overall education of students, since one of the main objectives of the education they provide is to provide broad knowledge of a civilizational nature, accompanied by the development of a reflective spirit on which the social dimension of the individual can be based. We have to agree: the general objectives of university education coincide to a large extent with the objectives of a humanistic education, in which the book, great literature, plays a central role.

If you could name a title to celebrate Portuguese Book Day, what would it be? And why?

In the spirit of Portuguese Book Day, which celebrates authors and the book as an object, one stands out immediately because it has been the subject of the most diverse and passionate polemics and has taken on the most diverse formats in a metamorphosis that speaks volumes about the public’s importance and appetite.

From the miniature and the pocket book that would allow every knight to “carry it with him everywhere he went”, to the luxurious edition volume suitable “to adorn the bookshop of any cultured man”, with precious engravings or illustrations, to the digital or facsimile edition, complete or anthologized and annotated, – everything has “dressed” the text of ‘Os Lusíadas’, which saw its first edition in 1572, in a book of relatively modest appearance, printed in Lisbon by António Gonçalves.

To conclude, is there anything you want to emphasize or add on this subject?

Returning to the timely examples you mentioned, Camilo Castelo Branco and Luís de Camões show what it must be like to train readers for life.

The school has to make people forget that Camões and Camilo are “program” authors. Even more so, it has to be pointed out that they go beyond the school walls. Indeed, we usually have our first contact with one or the other in formal education, just as we have our first contact with geometry, which accompanies us throughout life at school. Revising oneself in a few verses from ‘Os Lusíadas’ or ‘Rimas’, immersing oneself in the world of Basílio Enxertado Fernandes or crying, without shame, with Mariana, should be an exercise that is practiced throughout life.

Daniela Canha is a journalist for the newspaper Correio dos Açores-Natalino Viveiros, director

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks the Luso-American Education Foundation for their support.