In The Elderly (Os Velhos in its original Portuguese version), Paula de Sousa Lima offers readers an unflinching, lyrical meditation on aging, loneliness, and memory. The novel centers on the residents of a long-term care facility, particularly Maria de Fátima, an 88-year-old woman whose interior life is as rich as the institutional world around her is barren. But to reduce this work to the story of a single protagonist would be to miss its broader, more haunting achievement: The Elderly is a choral novel, a tapestry of muted voices and silenced selves, where each resident—drooling, stumbling, dreaming, forgotten—contributes to a collective elegy for those whom society has set aside.

As Maria de Fátima reflects, “We are all alone, although quite a few of us exist.” That devastating paradox captures the emotional core of the novel: a place full of people who have become invisible, even to themselves. There is no melodrama here. De Sousa Lima eschews sentimentality in favor of quiet, cumulative sorrow delivered in precise, unadorned prose. What emerges is a deeply human story about what it means to age in a world without time for the aged. It is not a call for pity. It is a demand to be seen.

The nursing home is described less as a refuge and more as a whitewashed purgatory. The walls are neutral, the temperature regulated, and the meals repetitive. The days unfold in relentless routine—tea at eleven, soup at noon, soft cookies at four. Time flattens. Every hour resembles the last. And yet, within this monotony, the residents’ inner lives flicker with intensity, marked by fragmented memories, anxiety, longing, and moments of startling clarity.

Among them, Maria de Fátima remains the emotional anchor. A once-proud, devout woman who has now forgotten how to pray, she mutters through rosaries that no longer offer comfort, out of habit rather than faith. Her sense of self has begun to dissolve. Words she once cherished—God, hope, home—no longer resonate. But she is not alone in her unraveling. Around her are others: Mrs. Ernestina, tied upright in her armchair by a bedsheet so she doesn’t fall forward; Mr. Alcino, humiliated by incontinence; Mrs. Alzira, endlessly burping and spitting into a cloth. Each character carries not only the weight of age but also of societal erasure.

Though not cruel, the home staff treat the residents with mechanical detachment. Dr. Helena, the facility’s director, favors efficiency over empathy and order over human connection. A trained sociologist, she enforces rules with clinical zeal: lights out at nine-thirty, prescribed pills for every emotion, visitors restricted to hours that do not disrupt “the routine.” The elderly are considered problems to be managed, not people to be engaged. They are referred to in shorthand—deaf, senile, incontinent—as if the body’s decline were a moral failing.

Still, The Elderly is not a novel of helplessness. There is resistance here—quiet, persistent, and often poetic. Maria de Fátima resists not by shouting but by remembering. Or trying to. Her dreams are vivid, unruly, frequently terrifying, and more alive than her waking life. In one, her dead brother returns with three arms and hollow eyes to free her from a suffocating wall of yellow roses. In another, she soars over rooftops with Luís, her first love, their hands bloodied and joined before crashing back into the reality of age and grief. These dreams are grotesque, surreal, sometimes absurd—but they are hers. They are where her life continues, even as it dissolves elsewhere.

The novel is deeply interested in language—not just the spoken kind, but the inner monologues we use to assemble meaning. Words are slowly abandoned by the elderly, not by choice but neglect. “Words cannot resist living apart,” Maria de Fátima reflects, having lost the ability to communicate with her children, doctors, and herself. As memory deteriorates, so does language—and with it, dignity. De Sousa Lima masterfully captures this disintegration through prose that becomes increasingly elliptical, echoing the broken rhythms of thought.

Yet even here, there are moments of profound humanity. When a new resident arrives—an older man whom Maria eventually recognizes as Luís, the boy she once adored—her heart stirs. But she hides her face, afraid of being seen in her decay. “Don’t look at me,” she thinks. “Don’t look for anything in me that could remind you of the girl I was.” The shame of aging—internalized from a youth-driven culture—becomes a final cruelty. And yet, this recognition, even if unspoken, restores something that was thought lost: the sense that a full life and a full self still reside beneath the surface.

The Elderly is also a meditation on time—how it is experienced and lost. In the home, time no longer moves forward. It circles itself, diluting identity and stripping experience of significance. “Today is the same as yesterday,” Maria reflects. “Tomorrow will be the same as today.” But her past—the time she spent in the Azores, in a household filled with music, embroidery, and silent longings—is preserved in memory, and it is there that she and the other residents truly live. The past is not merely nostalgia; it is resistance. It is a refusal to accept the flattening of their lives into mere logistics and schedules.

For Portuguese-speaking readers, especially the Azorean diaspora, The Elderly resonates with even deeper cultural significance. Traditionally, elders were the backbone of the household—storied, respected, and deferred to. Their displacement into institutions is not only a practical shift but a cultural rupture. De Sousa Lima’s novel is not simply an elegy for individual lives. It is an elegy for a social structure where elders once had centrality and now are peripheral, silenced, and managed.

At a time when aging populations are expanding globally, this novel arrives as both literature and a mirror. It invites readers to confront how we treat the elderly, not just in nursing homes but in our homes, policies, and imagination. Do we still see them as living? As a feeling? Do they need beauty, variety, and connection? Or do we, like Clara—the efficient, impatient daughter-in-law—see them as liabilities to be “placed” somewhere safe and out of sight?

Paula de Sousa Lima does not answer these questions. She poses them with gentle insistence, trusting the reader to feel the implications. Her gift is not only her language—though that, too, is remarkable—but her ability to breathe life into characters whose lives the world has deemed finished. She grants them not just memory but presence, grief, and grace.

The Elderly is a novel about many things: the erosion of memory, the politics of elder care, the terror of dreams, the persistence of identity, and the quiet heroism of those who keep living after they’ve been forgotten. But above all, it is a novel about dignity—the struggle to retain, recognize, and extend it to others.

In its muted chorus, we are reminded that every life—even when reduced to silence—is still saying something. We just have to be willing to listen.

by Diniz Borges, translator

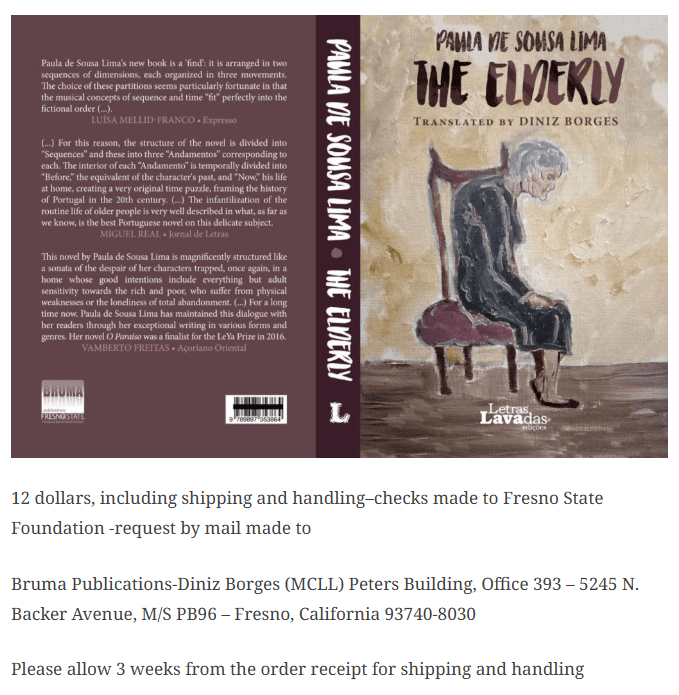

To order the book in the US and Canada.

Some images from Letras Lavadas at the event held in São Miguel, Açores

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for their support.