Since its founding in 1991, SolMar has been a meeting place for writers and readers, accompanying generations and establishing itself as an essential space in Ponta Delgada. In this interview, José Carlos Frias revisits the bookshop’s history, recalls the great names who have passed through, and reflects on the future.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: Livraria SolMar was born in 1991 in a context where the concept of a bookshop in the Azores was different. What motivated you to open this space, and what was your vision for the bookshop?

José Carlos Frias (founder and owner of SolMar)

-I worked for about eleven years in the only existing bookstore, Livraria O Gil. I started around 1979/80, and it was there that I did all my apprenticeship with Mr. Gil, a man with a great capacity for adaptation. We were there in the post-April 25 period, when literature in the Azores and the country flourished, when banned books began to be published. It was an extraordinary decade for national literature, but it was also when a golden generation appeared in the Azores – of great Azorean creators connected to the region.

Mr. Gil was a master and a friend. Even after the bookshop closed, we maintained a close relationship. When I opened SolMar, I was 22 and needed the support of two partners. We were from different generations but united by our love of books. Albano Pimentel—the late Albano Pimentel—was passionate about literature and a regular customer of Livraria Gil. José Garcia, for his part, brought an essential component of management and finance, helping us structure the project.

Our aim was to modernize access to books, which came to fruition with the opening of the SolMar shopping center in 1991. The great innovation was computerizing the bookshop, something unheard of then. This allowed better stock control and quick access to information.

We were also disruptive in transforming the bookshop into a space where people could browse books freely, without counters separating readers from books. We wanted it to be a second home where contact with books was natural, and there was no obligation to buy.

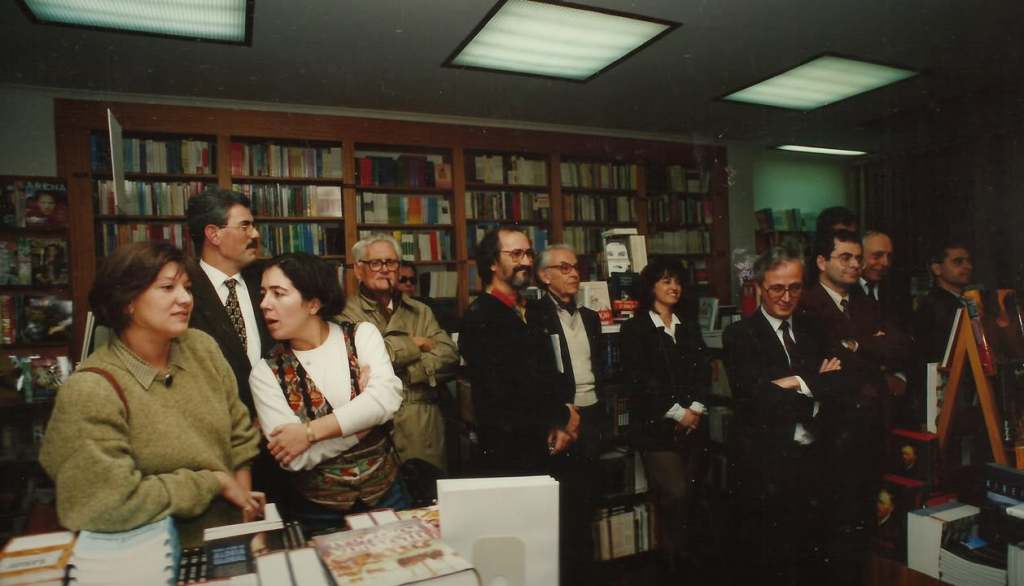

Cultural dynamization was another pillar. In 1991, Ponta Delgada had few spaces for cultural sharing. Since the opening, we’ve brought in writers for presentations and launches. On the first day, we brought together a large group of Azorean writers and brought António Lobo Antunes for a public session – he was the bookshop’s godfather. The late Daniel de Sá, a profound connoisseur of his work, introduced the event. That’s how we started, and we’ve never stopped.

Many names have passed through here. José Cardoso Pires, for example, stayed with us for a week, participated in sessions, gave interviews, visited schools, and demystified the writer’s figure. We always tried to break down the idea that the writer was an untouchable being. Later, we welcomed José Saramago, already a Nobel Prize winner, and, more recently, Manuel Alegre.

Before the emergence of professional galleries, the bookshop hosted visual arts exhibitions. We had a wall dedicated to this dialog between the visual arts and literature—it was very important during that initial phase.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: From the outset, SolMar stood out for promoting a strong cultural agenda. What moment or event has most marked you in these 34 years?

– No doubt about it. One of the most memorable moments was when we managed to bring together almost all the creators from the Azores. We had, for example, Emanuel Félix and Álamo de Oliveira, from Terceira, alongside our local writers, such as Emanuel Jorge Botelho, our great living poet and one of the best poets at a national level.

The highlight of the bookshop was the constant presence of these authors. They came in every day and shared their wisdom and knowledge with us. I remember a conversation with Professor Machado Pires, perhaps the last of the great Azorean thinkers, who has also passed away. He said: “Anyone who works in a bookshop, who owns a bookshop, is either already cultured or is becoming cultured. You can’t escape this fate.”

The diaspora was also important, and we welcomed those from abroad very well. One name who came to live here, who stood out immensely at the time and has continued to do so, was Vamberto Freitas, a literary critic from the United States.

In other words, in the 80s and 90s, a generation emerged that was reflected in various genres: fiction, novels, short stories, novellas, poetry, dramaturgy, theater, critical essays… And the highlight was this: the bookshop had the privilege of accompanying Azorean culture at its peak—it is made of this; they were the basis of its continuity.

Therefore, the bookshop’s history is inseparable from that of this very strong generation of great talents who had an immense desire to share their work and an unconditional love of books. This has enabled us to survive and have such a strong cultural presence. They found a space where they felt comfortable and welcomed, could share with the public, and created cultural dynamics. This was the high point of the bookshop.

CORREIO DOS A”CORES: The bookshop’s longevity is undeniable, largely due to the people who have passed through and helped build it over the years.

That’s for sure. There was this ambiance. I don’t really like the word “tertulia”, but our “tertulias” were spontaneous and never organized. They met and shared ideas, and the bookshop became a hub for sharing and motivation to create. And even a kind of ‘grafting’, in the good sense of the word ‘graft’: a positive contamination.

This environment meant that writers met, shared ideas, and influenced each other. From this exchange, literary supplements, congresses, conferences, and book launches with large audiences emerged, something that until then hardly existed because there was no space where they could share their work.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: How do you see the role of Livraria SolMar in training new writers over the years?

– That’s very interesting because we’ve always felt the need to welcome young creators, the youngest, who were almost taught by their elders. In other words, the younger generation was also essential for renewal, for this constant rebirth of the bookshop’s spirit.

I’m thinking, for example, of Nuno Costa Santos, who started writing even before he went to university. He had contact with Dias de Melo and other writers he idolized, and this ended up creating a spirit of creative ambition. The same happened more recently with Leonardo, an extraordinary poet whom I’ve known since he was very young. Or Joel Neto, from Terceira. He started out in the sports press and was already taking his first steps as a novelist and columnist – and he’s an excellent columnist. When he came here for the first time, he found his idols, his references, in the bookstore. He made friends with João de Melo and many others. I also include Daniel Gonçalves, from Santa Maria, who comes here every time he passes through Ponta Delgada. We formed a strong friendship because of this. Transiting between Santa Maria, São Miguel, and Lisbon is part of his life because he never misses an opportunity to drink culture, see concerts, and nurture his art elsewhere. But passing through the bookshop always brings us poetry.

COORREIO DOS AÇORES: The book sector faces constant challenges, from digitalization to competition from the big platforms. How has it been managing SolMar in the face of these changes?

– The hardest thing is always tomorrow. We’ve never been against progress and we’ve always seen technology as a contribution to the dissemination of books and reading. Until we reached a point where the way technology was used began to be counterproductive to our promotion mission. Livraria SolMar’s main mission has always been to encourage reading and create new audiences – this has been achieved with these dynamics.

What I now see as counterproductive about new technologies is their misuse, for example, in digital education. We’re not against digital literacy, but we really need analog literacy first to move on to digital literacy. In other words, combining the two allows us to achieve a certain balance.

Books still have their place because there is a human need to fix the text. The fixation of text on paper remains forever in history. And they still haven’t convinced me otherwise. Hard disks fail. Today, an accessible file may be obsolete in a few years. The letters we used to keep have become emails, but the archive of digital memories is fragile. As Emanuel Jorge Botelho used to say, “paper is very generous, it accepts everything we put on it”. But that also brings with it a responsibility: when we write, we must think about what we’re leaving behind for posterity. It won’t hurt the world if we do it in a relaxed way and if there are lots of people writing. Time is a sculptor. It does the sorting itself, but there must be a record for that to happen. That’s why mediators – bookstores, libraries – remain essential.

If man hadn’t established the first languages in caves, we wouldn’t know anything about the first civilizations. We wouldn’t have any memory if we didn’t have papyrus, parchment, and printing presses. Anthropologists teach us that. History teaches us that. To have a good present and a good future, we need memory.

Today, we live in a globalized world, and despite all the attempts to close borders and build walls, art prevails—it remains the great weapon in this fight against evil. Art awakens creators, even in difficult times like those we live in today when evil is converging to end the world—so say the prophets of doom.

The world is indeed sick, but if we look at creation, it continues to innovate. Poetry continues to emerge—above all, it brings us those moments of beauty that are fundamental to our lives and spirits and gives us the strength to wake up in the morning.

A child’s cognitive development begins at an early age. Even without mastering language, the brain works like a sponge from an early age, absorbing everything around it. That’s why language is essential to children’s growth – and books play a fundamental role in helping to shape them into better people. You might say, ‘ But Hitler had a big library’. Yes, that’s true. But, according to researchers, the books he went through, the ones with his digital imprint, were the worst in the library. The rest were just there for the record – the great classics and whatnot, because that was already part of it.

So books bring good, and good brings humanity, wisdom, knowledge, and memory. What new generations often lack is precisely memory. And that brings us to an essential point: education. Education, education, education – for reading, for the arts. All this, when combined with scientific knowledge and technology, does not harm the world. On the contrary, it can contribute greatly if put to good use.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: In 2000, the Artes e Letras publishing house was born. How did this initiative come about, and what is its editorial line?

– Editora Artes Letras first emerged within its parent company, Livraria SolMar. Right from the start, we published very carefully, because we were a small label and we wanted to publish works that we felt were missing from our daily lives – books that people were looking for and that we didn’t have to offer. At the same time, we also started to invest in new creators, publishing some of their first works.

Later, the publishing house gained autonomy – like a child that grows up and goes its way. Today, Editora Artes e Letras no longer belongs to the bookshop and is managed by Maria Helena Frias. We’re all still in the same house, but after this editorial maturation, handing over certain areas to someone who had training became essential. And so the publishing house has grown within its means, always adjusting to the market’s demands – a market that dictates the rules and has its own dictates.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: Looking to the future, what can we expect from Livraria SolMar in the coming years? Are there any new projects or changes on the way?

– Yes, there is a need for constant change, and we are prepared for that. Every day, when we enter the bookshop, we have to have this spirit of listening: listening to others and understanding what’s going on around us. It doesn’t make sense to think about the present and the future in the same way as we did in the 1990s and 2000s, at the turn of the century, with all the upheavals.

Therefore, our main focus is this constant struggle, which is essential and makes all the difference in a small society like ours – to guarantee the continuity of this spirit of mission: to get people reading, to encourage reading, always maintaining the principles that have brought us this far, but looking to the future, so that this link to books and reading is never broken.

The book is a great object of creation. We get a record of our lives through a novel or a book of poetry, just as Camões did. We are now celebrating the 500th anniversary of his birth, and he told the epic story of Portugal in a great book, Os Lusíadas. We can sometimes criticize how his work is taught in schools because Camões’ poetry is great and could perhaps be taught differently. But I’ll leave that to the pedagogues and specialists.

In any case, our perspective for the future is to continue to see this as a great epic. The journey is not over yet, and we are still here, with all our efforts, fighting against the many evils that appear to us daily.

I have this reference that Mr. Gil always passed on to me – and I owe him that tribute. At the time, new means of distributing books were already emerging: we had reader cycles and door-to-door sales, and now we have the internet and online commerce. All of this inevitably has an impact on our work. There were many difficulties, but there was something he told me that I’ve remembered all my life: ‘We don’t have competitors; we have colleagues.

Unfortunately, on the other side, sometimes they don’t see us as colleagues but as competitors, following the merciless laws of the market – this savage capitalism. A megastore of so-called ‘cultural’ products may appear in a few days, and the city will be ready to welcome it. But that’s another challenge, another struggle that we’ll have to face. And for that, we rely on people because if we don’t sell books, we can’t survive. People love us every day when they buy a book from us.

My big appeal is for people to create their own family libraries. This is fundamental for their children. In addition, it’s worth noting that school libraries urgently need more resources. If there were millions of euros to buy computers and implement digital education, why not invest a few hundred euros to equip school libraries? Give them something new, books that meet the needs of young readers and interest them.

That’s the big question: one thing can’t kill the other. Just as television didn’t kill radio, neither did cinema. Each medium finds its own space. But why? Because there’s the pleasure of watching a movie together, in the dark, on a big screen. Some movies are made to be seen like this. In the same way, some books can only be read on paper. A physical book arouses emotions and activates the senses – the smell, the touch, the real presence of the object.

We live in a society of images. That’s why it’s essential to create counterpoints – we spend all day looking at screens, working tiredly. We need to compensate for this. Why not with a book, a good movie, a good exhibition? Virtual visits to museums are useful when you can’t travel, but they don’t replace the real experience. Seeing a Van Gogh painting in person differs from seeing it on a computer image. Of course, those who don’t have this possibility or who have never had this privilege don’t lose everything by seeing it like this. But you can also find that in the pages of a book, duly contextualized and explained.

The difference between good and evil, between truth and lies, is in books.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: The bookshop is now celebrating its 34th anniversary with the launch of a new book by the poet Daniel Gonçalves. What can you anticipate about this event? What does this celebration mean to you?

– This is a special day because we’ve combined several important things. Personally, I really enjoy celebrating world days, whether it’s World Book Day or World Poetry Day. March 21 is doubly symbolic: as well as World Poetry Day, it’s also World Tree Day – a symbol of life, nature, and the art of storytelling itself.

This year, we have the privilege of having one of the best poets of his generation, Daniel Gonçalves, who comes from Santa Maria and has agreed to be with us to launch his book, published by Editora Artes e Letras, which is, in a way, the daughter of Livraria SolMar. This is a party!

The session is open to the public. We will celebrate 34 springs and poetry because we can’t live without it. We can live, yes, but it’s not the same. Poetry gives us a happier way of being in life.

We want to celebrate this date by bringing together friends, book lovers, writers, and readers. We want to bring joy to the city, the island, and the region. Right now, the world needs poetry. It may sound like a buzzword, but there is a real need for poetry worldwide. We live in times of great upheaval, wars, and unpredictability. That’s why we want to commemorate and highlight the importance of these moments.

CORREIO DOS AÇORES: Is there a book or poem you’d like to leave our readers on this World Poetry Day?

I have a text on my wall that is practically a poem. It was written by Emanuel Jorge Botelho and is called “Benefits of Reading.” It started as a chronicle published in the press many years ago but ended up being published as a book. I really like this text, and although it’s almost as old as the bookshop, I think it’s still extremely topical. It ends by saying “Turn off the television”, but today we can imagine a complement: “Turn off the internet when you read a book”.

Daniela Canha is a journalist for Correio dos Açores, Natalino Viveiros, director

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks the Luso-American Education Foundation for their support.