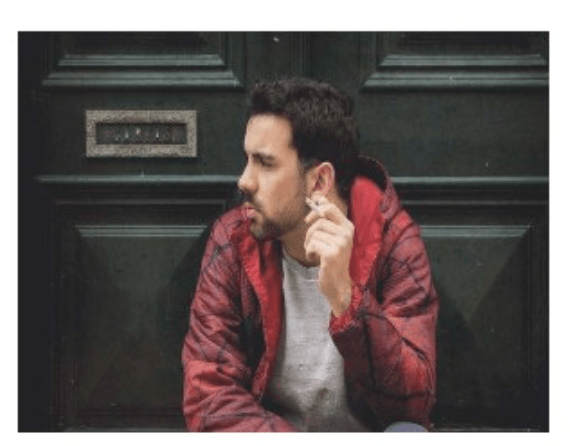

On World Poetry Day, we spoke to Leonardo Sousa, an Azorean poet born in 1993 in Ponta Delgada and the author of works such as Há-de flutuar uma cidade no crepúsculo da vida, âmbula, caderno de mitos pessoais and contas de cabeça. In this interview, he discusses poetry. Between literary references, philosophical influences, and a critical view of the present, he discusses the Azorean cultural scene, where there is no shortage of artists but a shortage of investment and public education. With no illusions about the times we live in, he says that poetry is not measured by its usefulness, but by the way, it unburdens us and forces us to look for other places.

Correio dos Açores – World Poetry Day. Anything to point out?

Leonardo Sousa – Not so much about the World Day, but about the time itself. 48,000 dead in Palestine, plus a few hundred thousand more since the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The planet burning on one side and flooding on the other. Monsters in power or on the verge of it: some brainless but surrounded by dangerously intelligent people. The richest man in the world says that humanity’s greatest problem is empathy. Humans become mechanized, and machines become humanized. This is a feast for poetry; poetry feeds on beasts much more than flowers and birds. I’m reminded of Nicanor Parra: “You can’t get rid of the statue of any president / (…) // The pigeons know very well what they’re doing”.

Are there years when poetry is more necessary than others?

As a friend recently said, we’re clicking too much on the interesting times button. I don’t want to say that poetry is necessary; I think it’s absolutely useless, and that’s the only reason it’s survived the millennia; that’s the only reason it’s worthwhile. Toilets are useful and necessary; I don’t know who wrote or said that, but it’s true. Poetry is not measured in these parameters. There’s plenty of raw material to write a poem in the 21st century, in 2025, that’s for sure.

For the epigraph of your second book, you chose the phrase ‘a poem should be, not mean’. What does that mean?

It’s a line from Archibald MacLeish, an American poet from the 19th century. At the time, his intention with the epigraph was to affirm the poem as support for itself, to establish it not as a work but as an organism, made up of vulnerabilities and contradictory possibilities of meaning, at once perennial and perishable. A poem clouded by static attributes, which doesn’t move within itself, which doesn’t resist what I can say about it, is of little or no interest to me. I believe in poems like earthquakes: forces from the nuclear depths of the earth that devastate, recreate, transform, make us homeless, and force us to look for places to hide – precariously.

Virginia Woolf said that prose will never hit us with a single blow’ as only the poet can. For you, what makes poetry so powerful?

It depends on the prose and the poet. These categories and divisions are a bit pointless, even counter-productive and emasculating. For me, and I’m only answering in my case, it depends on how concisely I manage to say what I didn’t intend to, what appeared on the page after an exercise in manipulating and saturating the possibilities of the text. The strength is the blank spaces left in the words and the words behind the blank spaces. Of course, it is necessary for someone to write and for a certain (dis)concert of language to be inscribed, but the strength of poetry is above all a work of reading. The reader creates the poem almost as much as the so-called author.

What is poetry?

Herberto Helder: “It’s always something else, a single thing covered in names.”

Do you remember the moment you realized you wanted to write?

When I was seven, for the first time. And a long break after that, at fifteen or sixteen, when I started writing short stories and poems, not bad for a kid that age. May the trash have them in a good place.

What are your literary references?

Whenever I’m asked that question, I have to browse the bookshelves, and the answers depend greatly on the moment. I have the Epic of Gilgamesh on my desk, Vol. IV of the Bible translated by Frederico Lourenço (specifically, open to the book of Ecclesiastes), Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and Lucretius’ On the Nature of Things. But Pessoa, Beauvoir, Lispector, Herberto, Cesariny, Al Berto, Ramos Rosa, Lobo Antunes, Natália Correia, Emanuel Jorge Botelho, Bukowski, Nicanor Parra, Gonçalo M. Tavares, Nuno Félix da Costa, José Luiz Tavares also come to mind.

What about other references?

I don’t know; between philosophy, the arts, politics, and everyday life, there are so many things, and they’re so random. Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Freud, Marx, Antero’s essays, the existentialists in general, Sartre, Camus, and Beauvoir, were fundamental to building the way I think today. I found a kind of family in post-structuralism and cultural studies because, from a very early age, I sensed that Western civilization was based on criteria of truth that were too convenient. Foucault, Judith Butler, Bell Hooks, Anselm Jappe. On the other hand, it was a disappointment because it turned out that they had thought of everything I thought I had discovered on my own and in a much more intelligent and sustained way. In politics, my heroes are Allende, Mujica, and Emma Goldman. In music, those who move me, for very different reasons, are names like Zeca Afonso, Zeca Medeiros, Tom Zé, Elis Regina, Luna Pena, Da Weasel, Debussy, Miles Davis, Nirvana, Arctic Monkeys. In painting, my favorites are Francis Bacon and Richard Lindner, and in cinema, Orson Welles, Billy Wilder, Kubrick, Kusturica, and David Lynch. The other references are strictly affective and too personal to be listed here – although any reference refers to an intimate space. We may have similar references but rarely have them for the same reasons.

How did you get here? How does one become a poet in the Azores?

It was quite improvisational, without any great calculations or plans. It was a sequence of accidents that I never really saw as a path; I’d have to look back and put them together in a kind of mental studio (I’m stealing the image from a poem by Urbano Bettencourt), which would always be more an exercise in fiction than anything else. I’ll answer you with a question: how does someone not become a poet in the Azores?

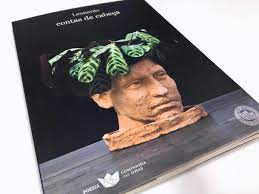

Once a city has floated away in the twilight of life, it’s on to the moonlight, the amber, the notebook of personal myths, the correspondence, the accounts in your head. Is there a book that you identify with the most? Can you talk about any of these titles?

In the first two, I see myself from a distance; I only recognize myself based on certain traits. ‘Ambula’ was important; I’d never written in such an anarchic register. Carlos Alberto Machado, editor of Companhia das Ilhas, himself a very strong poet, let me loose, gave me clues to problems, and forced me to find solutions independently. In short, he gave me freedom. I think I’ve been working on a personal re-signification of the lyrical representation of reality. I think the lyricism of Notebook of Personal Myths is far more ironic and scathing than a superficial reading might presuppose (Manuel de Freitas pointed this out in his review), which is why the head-on account has put some readers off; the self-ironic dimension is accentuated, there are more abrupt cuts, more ellipses, it’s a book whose principle is to “turn the skull into a minefield” (Robert Bréchon). I like this idea of constructing a trapped lyricism, almost an optical illusion, a beautiful tree that throws birds in your face and hangs you upside down by your feet if you get too close.

Is the ‘island poet’ different from other poets?

It must be, just as an ‘urban poet’ differs from other poets. I could answer more confidently if someone could decently explain what the hell ‘an island poet’ is. To put it like that, it sounds like a label for a promotional package. When you buy a poem, you get a pineapple and jam. That’s not why I write (not least out of respect for the pineapple and the jam). The relationship between art and geography has become very tired; it’s reached a point where it’s almost caricatured, especially in a globalized world, where the question is no longer posed in those terms. I could paraphrase Nuno Félix da Costa here and tell you that, where he writes “Portuguese only unites me with the dead of literature”, we could write “insularity only unites me with the dead of the insula”.

Poetry and art in the Azores… anything to report?

They exist and owe nothing to anyone. We Sea is about to release another album, but the first two are already musically and lyrically heavyweights. I listen to them a lot; they’re among my favorite bands in the national field. Rofino’s voice is amazing, but he’s also a very capable poet. The work that Romeu Bairos has just released and is promoting is extraordinary on many levels and I don’t know if, in terms of raw talent, anyone beats him, but I’m suspicious, we’ve been friends for a long time, and we’ve even written songs together. João Miguel Ramos and João Amado are playing very strong cards in the visual arts. On the block, there’s Mário Roberto, Vítor Marques, Leonor Pereira. In literature, there are lots of names. Whether you like them more or less, Paula de Sousa Lima, Madalena Ávila, João Pedro Porto, Joel Neto, Nuno Costa Santos, Maria Brandão, Urbano Bettencourt, Leonor Sampaio da Silva, Renata Correia Botelho, Emanuel Jorge Botelho are all on the map. In short, I’m leaving out many names and areas, if we don’t fill an entire page. The problem in the Azores isn’t a lack of artists; it’s a lack of audiences. There is no training of audiences because training audiences means training critical mass, which would be extremely inconvenient for the powers that be. And there’s a lack of investment in artists and culture because who knows what people like that can go around saying and demanding… Of course, there are the hired guns, who win all the competitions for everything, no matter how indigent the proposal, and, if you notice, for them, the Azores are always a fantastic, idyllic, wonderful land, a unique paradise. It’s always a privilege to live there, no matter how miserable life is.

Has Lisbon changed your writing? Are there verses that could only have been written in the Azores?

Those are questions for the readers. Probably yes, but I honestly don’t have enough distance from my work to answer. Probably yes, because creative experiences are almost always contaminated by the experience of places and times. But those who read will know best.

Do you have a routine or ritual for writing, or does poetry impose itself when it wants to? Where does inspiration end and editing begin?

I write when I know I can’t miss the phrase that came into my head. The ritual or routine begins when I sit down daily to revise, edit, and delete. And that’s when 90% of things are in the garbage can.

What are the things that inspire you?

Everything in general, nothing in particular. I write when I’m in a state of ecstasy, of particular joy or of revolt and anger, or when a text lands in my head, I’m not sure from where, more or less ready, just needing a little tweaking and a safe time away, which is one of the ways of testing the durability of the first impact.

Does the ‘muse’ exist? If so, what form does it take for you?

In general, inspiration, muses, fairies, gods, and daemons are fictions that we use to arrange things we can’t explain. Where does the urge to create come from? Why do you constantly think about translating what you see and feel into written form daily? Why do you keep trying despite a remarkable percentage of failures? I could tell you that I grew up among lots of books, among teachers who encouraged me, that my father painted, etc., but that doesn’t explain everything.

How do you decide that a poem is ready?

I don’t decide. I don’t have the finished poems but the final versions.

When is your next book coming out? Do you have any other projects in the pipeline?

The next one will be the reissue of the notebook of personal myths very soon, at the invitation of Artes e Letras. Taking advantage of the reissue, we will include texts left out of the first edition in 2018 and texts that appeared in the same publisher’s poetry edition of Avenida Marginal.

I have a book in hand, which was supposed to be published later this year under the Companhia das Ilhas imprint, but it’s frankly too late to fit it into an upcoming calendar.

What would it be if you had to choose one poem to keep in time?

I’d prefer readers to choose, and this answer would perhaps change tomorrow, but today, two, the first coming from the head accounts:

you fit in a hiding place

approach the opposite

step back towards the horizon

and remember

in the absence of a destination

everything is on the way

turn off the headlights and glide

under the roads the ditches roll

the real killers

obey the traffic lights

The second to come out, in principle, in the reissue of the notebook of personal myths:

too modern to read

how i learned to breathe by accident

never wanted to make sense

A verse that never left you.

David Jones of Llangwyffen: “If someone calls me home / I don’t know how to answer.”

A poem you wish you’d written.

I could make a collection of poems I wish I’d written. Today, one by António Ramos Rosa:

AGAINST PURE POETRY

Enough of stars

and clouds

and birds

Let’s talk about cages instead

It’s time to conquer the sky

What poem would you like to leave our readers on this day?

Among the many others that I do an injustice not to transcribe here, this one, by Ruy Proença:

Tyrannies

in the old days

used to say: watch out,

the walls have ears

so

we kept our voices down

policed ourselves

today

things have changed:

ears have walls

there isn’t

any use

in shouting

Daniela Canha is a journalist for Correio dos Açores.

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks the Luso-American Education Foundation for their support.