Monday the 20th was marked by several events that we can’t overlook, like “… a dog through a harvested vineyard.”*

As we all know, this is a return to which the world, for various reasons, is not indifferent. As far as I’m concerned, and for the time being, I have nothing to say, the choice, like it or not, was made by the American people and, as such, is as respectable as any other popular choice, and I say that I have a different view to that of the Democrats out there, for whom election results are only acceptable when they serve “their” purposes. The reference to one of the events has been made; whatever happens as a result of the actions of the new US administration will, in due course, be the subject of one or other note depending on its internal and external impacts.

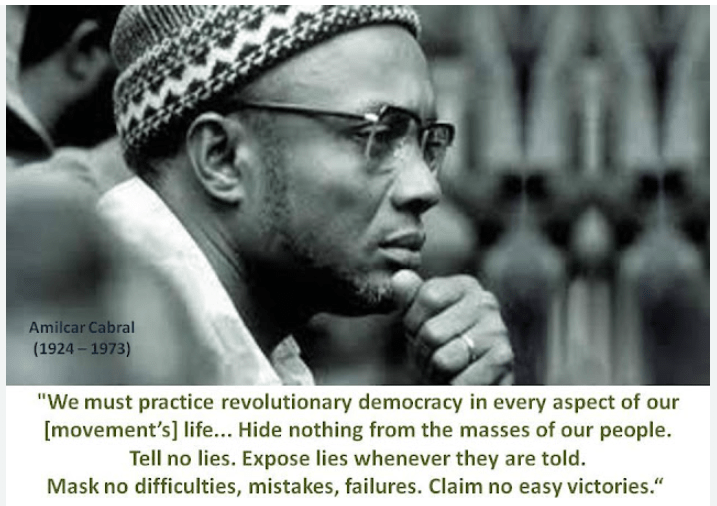

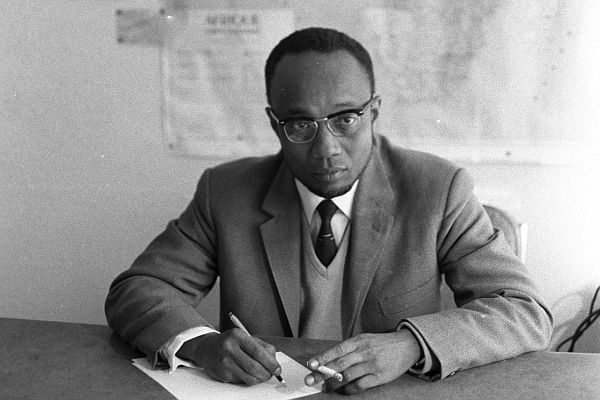

The inauguration day coincided with a holiday, one of three in the United States dedicated to a personality, Martin Luther King Day, a paradoxical coincidence. The holiday dedicated to Luther King falls on the third Monday in January due to its proximity to his birth date. This year, by chance of the calendar, a personality who is the opposite of a great humanist and a symbol of the struggle for civil rights in that country was sworn in as president of the United States. On Martin Luther King, a text by Diniz Borges was published this week in a regional newspaper, which I think is enough to honor his memory and struggle. I dedicate the next few words to another personality who, like Luther King, endures beyond his death: Amílcar Cabral.

January 20 marks the 52nd anniversary of Amílcar Cabral’s assassination, carried out by members of the PAIGC itself at the behest of the Portuguese colonial regime. More than his death, it’s important to remember his legacy, which is still a reference for the African continent and the world today and is, therefore, the object of attention in academic circles. These days, while researching Amílcar Cabral, I watched a video about women in the struggle for independence in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau, from which I extracted two phrases spoken by women that speak volumes about the man and his work. The context was the death of Amílcar Cabral, and I quote:

“(…) this came to an end, but then we saw that it wasn’t the end. That’s where Cabral’s value lies: projecting himself beyond his death (…)”. Zezinha Chantre.

“(…) we lost a great man, but he was able to transmit his strength to us in such a way that our struggle redoubled in intensity, and we reached independence without his presence, but with him in our hearts. (…), Amélia Araújo.

Guinea-Bissau’s unilateral declaration of independence came in 1973. It was internationally recognized, although Portugal only did so a few months after April 25, in September 1974, which raises, or may raise, some questions about the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary process of decolonization.

The Portuguese fascist and colonial regime called Amílcar Cabral a terrorist, but it was this same regime that pushed the liberation movements towards armed struggle by refusing all proposals for a peaceful solution to decolonization and independence. Regarding the PAIGC and the struggle for freedom in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau, we should bear in mind the memorandum sent to the Portuguese government in 1960 and the open note in 1961, which were ignored. The Salazar government’s action was to increase repression of the population and strengthen the military presence in a clear demonstration that the path to peace was far from the colonizing country’s intentions.

Amílcar Cabral was a multifaceted personality and a humanist. I know it sounds like a cliché, but I’ll still say that Cabral was a man way ahead of his time. Gender equality, sustainable development, and, therefore, environmental issues were some of his flags, along with social justice, the elimination of all forms of discrimination, and the fight against colonialism, which influenced his entire life and struggle.

One aspect of Amílcar Cabral’s thinking that most Portuguese will not be aware of, or at least not aware of, relates to his opinion on the end of the fascist regime in Portugal and the liberation struggle, about which he says the following: (…) We are absolutely convinced that if a government were installed in Portugal tomorrow that was not fascist, but democratic, progressive, recognizing the rights of peoples to self-determination and independence, our struggle would have no reason to exist. Therein lies the intimate link that can exist between our struggle and the anti-fascist struggle in Portugal, but also, we are absolutely convinced that, to the extent that the peoples of the Portuguese colonies move forward with their battle and completely free themselves from Portuguese colonial domination, they will be contributing in a very effective way to the liquidation of the fascist regime in Portugal. (…).

There’s no disagreeing with Amílcar Cabral. We are all aware that the wars of liberation of the peoples of the Portuguese colonies contributed significantly to the end of the Portuguese fascist regime on that April dawn. It was no coincidence that the Portuguese people took to the streets to support the armed forces’ movement that overthrew the regime, one of the reasons being the announced end of the colonial war, because all the families were suffering as a result of their sons going to war, a war that wasn’t their own, with all that meant. It wasn’t just that because many other contributions and variables can be said to have made April happen and, above all, for the paths of April to have always been present in May, despite the efforts to ensure that the Portuguese revolution went no further than handing over power to a former governor of Guinea.

The poetic side of Amílcar Cabral is not at all unknown to the Portuguese, and I bring it here to illustrate a lesser-mentioned dimension of this man of culture, this poem entitled: My poetry is me

… No, Poetry:/Don’t hide in the caves of my being,/don’t run away from Life./Break the invisible bars of my prison,/open wide the doors of my being/- get out…/Go out to fight (life is a fight)/the men out there are calling for you,/and you, Poetry, are also a Man. /Love the Poetry of the whole world,/-love the Men/Spread your poems to all races,/to all things./Confuse yourself with me…/Go, Poetry:/Take my arms to embrace the World,/give me your arms to embrace Life./My Poetry is me.

The poem was published in the 1946 magazine Seara Nova. Amílcar Cabral was 22 years old and studying agronomy in Lisbon.

*Portuguese popular proverb meaning: Passing unnoticed and without making an impact

Aníbal Pires is a retired educator. He is a political activist, poet, and contributing writer for several Azorean newspapers and media outlets. He lives on the island of São Miguel and has published poetry and chronicles in book form.

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL).

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for supporting PBBI-Fresno State.