SÃO PAULO, Brazil – On Saturday, I left the house in the late afternoon to do something I hadn’t done in years: go to the movies. I mean going to a street theater, as we call it in Brazil. Internet movies have taken away this pleasure, and we’re increasingly isolated in our homes. Also, the streets are dangerous. Nobody kills more than the police.

Getting to the movies, buying a ticket, going in. Although today, we buy tickets online. A returning pleasure, meeting friends, feeling the audience’s pulse, chatting after the screening. Habits gone. It was amazing to arrive at the theater to watch “I’m Still Here,” the moment’s sensation. And I’m talking about a movie theater in the middle of Avenida Paulista, in São Paulo, the capital of the economy, of wealth, of the upper middle class and of the bolsominos, as we call the scum of the followers of the ex-president with twenty lawsuits on his back. Arrive anxious and find a crowd gathered on the sidewalk or lined up in front of the ticket office and another line to get in.

It was amazing to feel the atmosphere of expectation, calm, cordiality, laughter, and kindness in the apparent confusion. The Brazilians are happy. Happy with Fernanda Torres. For weeks now, there has been a gigantic change in the Brazilian atmosphere. There is an air of happiness. A sense of well-being. For movie-goers, I say it’s been many years, and I mean years since we’ve seen queues and crowds of this size to see a Brazilian movie that isn’t a vulgar comedy, a naughty romp, or a mediocre musical.

No, we were there to see a dramatic, heart-wrenching movie. “I’m still here,” I repeat Fernanda’s movie. A true story based on the life of the engineer Rubens Paiva, who, in the 1970s, disappeared from his home and was taken away by the dictatorship’s police. He disappeared and was never heard from again. There is a version that he must have been thrown overboard, like dozens of others, in the navy-air force collusion established here between 1964-1985.

Watching a movie about freedom during a democratic period, knowing that everything is true, one of the bitter chapters of the military dictatorship that is still in the soul of many politicians, is a tough moment. And everyone there was feeling the reaction of being Brazilian at this time. There was an air of contentment. Seeing what had been forbidden for many years. I’m talking about the experience with Fernandas, mother and daughter, and Marcelo Rubens Paiva, one of the most resilient people in this country, who has done so many works in which he sought the truth. As well as Walter Moreira Salles, whom the reactionaries are hating to death – which is normal. Think about it, a millionaire, handsome, from a traditional family, intelligent, a great filmmaker who has everything it takes to be of the most absolute right and making a movie like this! You can’t imagine the plagues and the hurricane of posts that have fallen on him and his actresses.

All useless, elbow-pain. The movie is damn good. It’s been a long time since a film has been crowned by the Golden Globe. Give it to Fernandinha. I cried at the movie because, like my father, I’m a tough guy. This is a rare moment in Brazil. We haven’t felt such a sense of freedom for a long time.

As if the Bastille had fallen. A new Carnation Revolution here, hunger, illiteracy, and racism gone.

The truth on the screen not only anguished us but washed our souls clean, and at the same time, we saw an exceptional performance by Fernanda Torres; we saw the actress who doubled Hollywood and brought home the Golden Globe. As the movie played, we felt anguish at all that had happened, mitigated by the fact that it could be shown. A feeling of freedom and joy, like when Brazil was the world champion in soccer, tennis, surfing, and rhythmic gymnastics.

We’ve had a dark period with Bolsonarism, terraplanism, the “cattle” of total corruption passing unscathed, senseless deforestation, the crushing of the arts and the intelligentsia, and unlimited support for fascism. “This movie has given us encouragement. The offices of hatred, created by Bolsonaro, worked at full speed, trying to suffocate beauty and harshness and vilify humanity. But who cared? The movie won everything, won over audiences, won over public opinion. The fascists, the right-wingers, the cannibals despaired in the face of a film/document, human/difficult to swallow, revealing the sordidness we went through between 64-85. A movie that is free and brings millions of spectators – that they, the bolsominos, never expected – into the theaters. These crowds, which fill cinemas every week, irritate the generals (one of whom is in prison as a coup plotter), the scumbags, and the cultists of backwardness who hate the truth.

Ah, those Fernandas! Mother and daughter. They are in all our hearts. Mother and daughter on the altar of every home. The Golden Globe was the world’s recognition. Bowing down to the truth and beauty of exceptional performances. Kneeling before them are the Fernandas, who are the greatest figures of our stages, cinema, and television.

We’re happy; few can calculate how! Ah, the Fernandas. I met Mom in 1958 when I was 22, that is, 67 years ago, already an excellent actress, on the night that Yvone Fellman, a journalist for the newspaper “Ultima Hora,” where I worked in São Paulo, took me to her dressing room after we had watched Pirandello’s “Dressing the Naked”, directed by Gianni Rato at the Teatro Brasileiro de Comédias, the temple of theatrical modernization in Brazil. That’s where our friendship began. Yvonne now lives in Lisbon, the widow of Portuguese journalist Victor da Cunha Rego, who lived in Brazil for many years. Fernanda’s daughter was the last person I saw in March 2022 at the Brazilian Academy of Letters when her mother was sworn in as an immortal. She was welcomed by Nélida Piñon, who, blind, was months away from her death in December of that same year. So Nélida, having written her inauguration speech and being unable to read it, asked Fernanda, her daughter, to read it. It was a rare moment of immense emotion at the ABL. A few privileged people participated in this unique, poetic, remarkable moment between the two Fernandas.

Now, Fernanda Torres has set Brazil and part of the world on fire. The rest will follow. How long has it been since Brazilians have been so free, so happy, packed into theaters by the millions with a drama that unmasks the dictatorship and its policy of torture? Going to the cinema and watching “Ainda Estou Aqui,” applauding the film in the opening scene and at the end, filled with revulsion at the monstrosity, is a moment to be celebrated. The Fernandas in a rare, relentless, restrained, heavy movie that we can watch without fear of leaving the room and being arrested. We’re not living in the best of worlds, but a spark of happiness has set this Brazil on fire. Fernanda Torres, to whom Eunice Paiva is from on high (I believe), thanks for the perfection of what she calls reincarnation. And Fernanda Montenegro, who, with a single minute-long scene, subtly moves her lips and eyes, tells us: “This is what acting is all about!” She’s been on stage and screen for almost a hundred years!

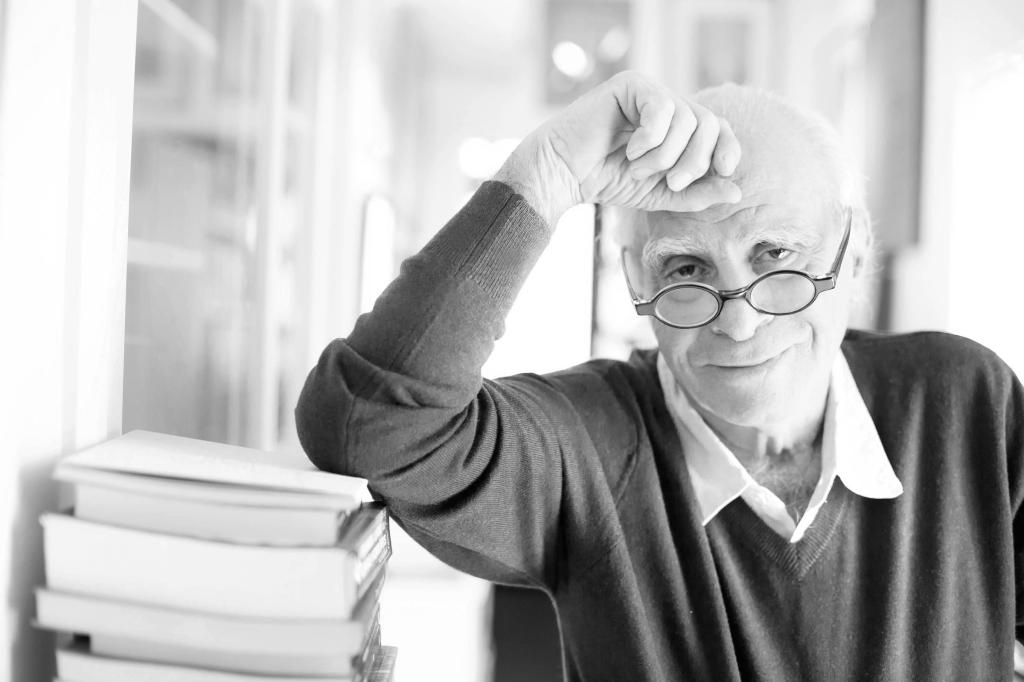

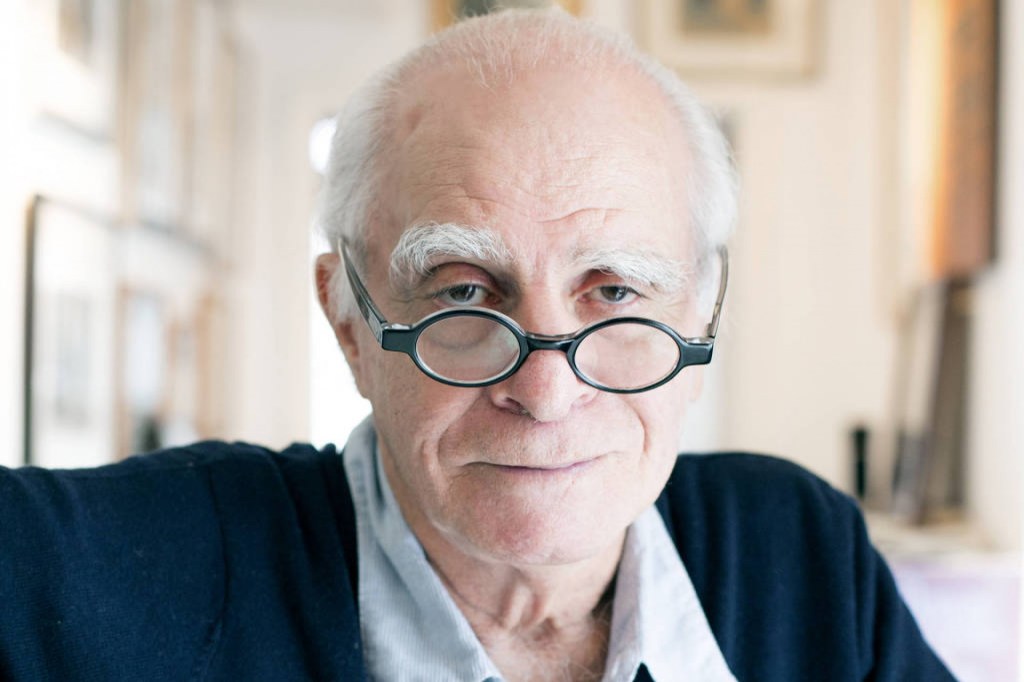

Ignácio de Loyola Brandão. A Brazilian writer and journalist, he is 88 years old, has published 58 books, including novels, short stories, chronicles, children’s books, and biographies, and has published 8,000 chronicles in newspapers over the last 40 years. He is finishing a novel about old age, “Risco de Queda” (Risk of Falling). He will be at the next “Correntes de Escritas” a premier literary event in a few weeks, held in Póvoa do Varzim-Portugal.

Translated by Diniz Borges

We thank the Luso-American Education Foundation for their support.