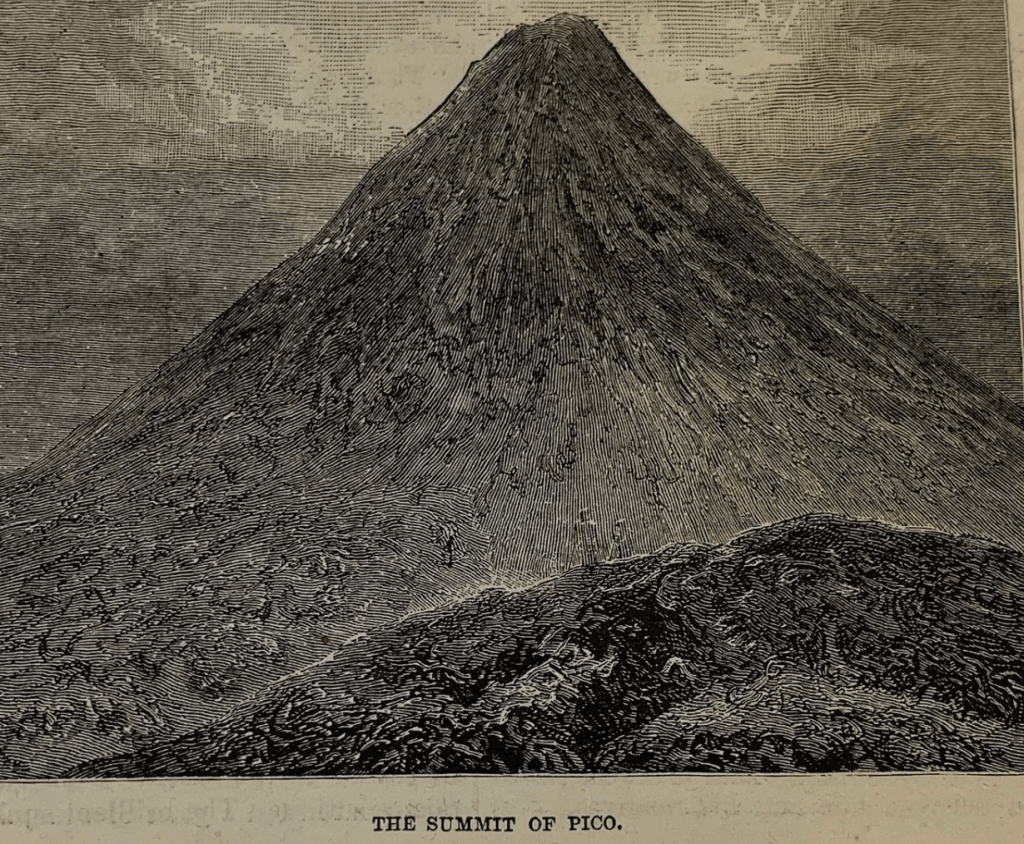

This is how Russell & Caleb Purrington saw Mt. Pico in their “Whaling Voyage ‘Round the World” ca.1848.

This text comes to us thanks to the research of Professor Emeritus Manuel Menezes de Sequeira, who is now living on the island of Flores and has done an extraordinary job in researching these stories, mostly from the 19th century. This one about Pico and Faial is from 1843. We are grateful to Professor Menezes for his work.

Awakened from my slumbers by the cry of “Land Ahead!” I repaired on deck, and beheld at the distance of seven leagues the islands of Fayal and Pico, shadowed darkly against the misty eastern horizon. For an hour I leaned over the side of our bark, watching the changing outline of Fayal, as our approach discovered new undulations and acclivities in its figure, and gazing with childlike wonder at the towering Pico, enwreathed with alternate zones of mist from its base to its summit, the latter visible for a moment to pay its fealty to the morning sun. To him who has been tossed for weeks upon the ocean, the land he makes must be hailed with thrilling sensations, though invested with none of the charms of beautiful and diversified scenery. But to him who leaves his country with the susceptibilities of impression peculiar to a sensitive youthful mind, and looks for the first time after his native shore has faded over the waters, upon a new world, attractive by the richness and variety of its drapery, the pleasure of arriving in port is immeasurably increased.

The wind being ahead, we directed our course for Pico, which on proximity to the island, presented an appearance inconceivably beautiful and majestic—its beauty arising from its luxuriant scenery, and its majesty from its elevation and insulated locality. At this time the peak was entirely obscured, and a vapory cloud encircled the mountain midway to its summit. By the aid of the ship’s glass I was enabled to enjoy one of the finest perspectives which it has been my pleasure to behold. The hand of cultivation has bestrewed these lofty regions with the richest landscape gardening to within one-third the extreme height of Pico, estimated at seven thousand feet above the level of the sea. The island itself, of volcanic origin, contains twenty-three thousand inhabitants. Here we beheld the natural wildness of the picturesque, blended with the fertility of cultivated districts, enlivened by the white cottages of the peasantry and monasteries and churches. On the west of the mountain, appeared numerous islets surrounded with rocks, over which the spray was breaking with such violence as to remind one forcibly of representations of the Eddystone light-house [na Cornualha, em Inglaterra] in a storm. Retiring to the cabin I penned the following lines.

In bold relief upon the eastern sky,

Espertal’s [?) lofty summit towers on high,

Around whose apex morning’s sunlight plays,

And in its blushing robes the steep arrays,

While circling clouds of varied hue are thrown,

‘Mid lucid belts, its sloping sides adown.

Ye who delight New England’s vales to tread,

When o’er her hills autumnal tints are spread,

No scenes of beauty joined with grandeur find

To charm the eye or awe like this the mind.

I’ve seen the sun light up the craggy brow,

And gild the depths of Horicon below;

While o’er that height and where those waters slept,

Tints upon tints in bright succession swept,

And hasted o’er the lake their rapid flight

High up the stretching hills that bound the sight.

But there are scenes far nobler to beguile

The wave-tossed stranger to this lava-isle.

Mountains there are, than Pico loftier far,

Whose heights so high, man’s footsteps they debar;

The sun itself does not, cannot dispel

The clouds that ever on their summits dwell.

On others, spring perpetual abides,

And beauty blushes on their fragrant sides,

While some in Alpine majesty arise,

Whose hoary tops reflected to the skies,

The chorus of that song creation sung,

When from its Maker’s hand the earth was flung

Among the stars, another witness given

To prove the wisdom and the grace of Heaven.

But grandeur, height and beauty, all combine

To form thy pageantry, Espertal, thine.

Nor these alone but clouds of features new,

With colors blending richly in the view,

And dark-blue waves that break with ceaseless roar

In clouds of yest [foam] upon thy rock-bound shore.

——

Visit to the Caldeira,- – The largest crater in the world

Henry M. Parsons

Caldeira signifies a boiler, in the language of the Portuguese, and is generally applied by the inhabitants of the Azores, to the hot springs which abound in many of those islands. With the prefix of the definite article it is used at Fayal, to designate the great extinct volcano in its centre by which that island was undoubtedly produced, at no very remote period. The voyager thither, seldom visits its most romantic and sublime scenery as the summit of the Caldeira is sixteen miles from the city of Orta, and the ascent exceedingly difficult and laborious. Our attention was directed to this spot by the American Consul, and we determined to gratify our curiosity by a visit, although forewarned of the expense to our physical energy, at which it would be purchased.

The general appearance of Fayal when viewed from the sea is that of conical hills rising higher as they recede from the shore and overlooked in the back ground by a lofty mountain. On a nearer approach, deep and extensive ravines are disclosed, while through chasms hollowed by torrents or volcanic action, cultivated hills invite by their dress of unusual luxuriance. In some places a solitary cabin stands on a beetling cliff—in others, a low, white cottage is planted in a vine-yard and shaded by orange and myrtle.

The island contains between twenty and thirty thousand inhabitants. The city of Orta, its capital, is situated on the eastern side at the bottom of a beautiful semi-circular bay, about two miles broad, with a grand amphitheatre of mountains above, crested with the evergreen faya from which the island derives its name. We had ascended a hill a mile from this city on our way to the crater as the sun arose. The elevated peak was before us, glowing in its beams, apparently very near, but in reality at the distance of fifteen miles. The varying rays of light produced by reflection upon the ferns or party-colored rocks afforded one of the most splendid exhibitions in optics we had ever beheld. The rude but neat dwellings of the peasantry are scattered along the road for three or four miles, beyond which the path is unrelieved by any vestige of civilization. At the base of the Caldeira we forded a muddy stream and began an almost perpendicular ascent of several hours continuance, halting occasionally to recruit our strength from the basket of the guide, or gather fresh incitement to pursue our toil in the mingled admiration and astonishment which a glance at the scenery beneath us awakened. When our cicerone who kept a little in advance, planted his foot on the edge of the mighty crater and shouted his triumph in his richest dialect, a view midway down the yawning abyss, paralized our remaining energies and we sank upon the shelving side of the mountain with a pervading sense of awful and unlimited grandeur. While our first impressions derived from a partial view were intense and overpowering, a momentary sight of the immense basin as a cloud settled into it, was not calculated to dispel or weaken them. From the narrow edge of the crater which is nearly level, circular and six miles in circumference, our eye fell more than three thousand feet upon a lake five miles in circuit from whose centre arises an indented cone of seven or eight hundred feet in elevation. When the cloud was lifted from the aperture, we stood for many moments in silent admiration of one of the grandest exhibitions of natural scenery which the earth affords, sensible of the weakness and insignificance of man and the limitless power of Him at whose voice the earth trembleth.

Most of the sides of the caldron shelve regularly, but in some places they are broken in, while ferns and clumps of myrtle or box hang in profusion from fissures in the precipice. At the base on the north side, huge fragments are strewed about; the large masses standing erect or piled irregularly upon each other, as we discovered by the aid of a glass, without which the most prominent objects were but indistinctly visible. The whole scene has a wild and sombre aspect from the water-worn lava, pumice, and every variety of rock met with at the island, which compose these enormous escarpments. The more elevated extremities of the strata towards the south, overhang each other, black and craggy, in the form of insulated columns. While we noticed one pyramidal mass of tuff near the summit, apparently six hundred feet in height, the stratification as beautifully preserved as in a work of art, a report like the crack of a rifle echoed and re-echoed from the sides of the crater and aroused our fears for the stability of our giddy platform. The assurance of the guide that a Portuguese at the bottom was employed in felling trees, did not dissipate them instantly. That one could descend, appeared so utterly impossible that we should have thought him sporting with our danger had we not discovered through a glass a moving speck that corroborated his assertion. It should be remarked that while the climate of the Azores happily precludes the necessity of wood for other purposes than those of preparing food, it is difficult to procure a sufficiency for this, and the reward of the woodman, reconciles him to his labor, though he passes days in the Caldeira and is obliged to lash to his back a few sticks at a time when he begins his incredibly toilsome ascent. Our guide pointed to a spot where we could test the practicability of a descent. We went down several hundred feet by a zig-zag, artificial path and abandoned our purpose of continuing to the bottom only because invited by the unsurpassed beauty of the scenery which a circuit of the summit promised. As we again attained the edge, a large sea-bird came sweeping in graceful circles from its visit to the lake below. As it passed above us, it seemed a beautiful similitude of the soul rising on the wings of faith from the caverns of despondence into the clear sunlight of unwavering trust.

The waters of the Caldeira though on a level with the sea are fresh, clear and less than a dozen feet in depth, abounding in beautiful but tiny fish. Those who have visited Vesuvius and Etna have seen a lake of fire raging continually beneath them, but if silence heightens sublimity they may behold at Fayal a grander reality than even those boiling lakes present. The mouth of the famous volcano of Italy, is less than two miles in circumference and that of Sicily does not exceed three and a half, while the Caldeira is more than six, with a depth exceeding either a thousand feet—such a depth that the wind never curled the sleeping waters—such a depth that the sunlight never played, nor a moon-beam rested on their bosom.

The circuit of the summit afforded us a rich prospect of twenty three villages surrounded with gardens and vineyards, scattered around the bases of numberless truncated hills. Across the channel arose the lofty Pico, its peak enwreathed with clouds or gilded with the sun. In the distance, St. George and St. Michael lay like specks upon the bosom of the quiet deep. The path we traversed was seldom more than ten feet wide, and in some places for several hundred yards, it was not three, with a precipice on one side many hundred feet, on the other as many thousand. We were singularly fortunate in the day we selected for the excursion as it is seldom that the mountain is free from clouds for a single hour. Once or twice while we made the circuit of the summit they curtained the view beneath us for a time, but when the sun poured its flood through their opening, deep and solemn emotions corresponded with the solemnity of the scene. But that which completed the magnificent picture was the beautiful and gorgeously sublime effect of sunset among the peaks below. To gaze upon the soft rich light as it tinged the lofty summits and glanced afar upon the mirror wave—to see the deep and spreading shade cast by the mountains on the sea in bold, fantastic forms—to behold a scene like this, was a climax filling the mind with a healthful relish of the majestic works of the Creator and lofty aspirations for that moral fitness which prepares the soul for contemplation of the unspeakably glorious scenes of Heaven.

Note from Professor Manuel Menezes de Sequeira, on his Facebook page where he graciously shared the texts above:

The first entry, the poem “Pico, in the Azores,” with a short introduction, was published on pages 36 and 37 in issue 1 of 1843 of the magazine “The Youth’s Parlor Annual,” volume 1. The second, the article “Visit to the Caldeira, the Largest Crater in the World”, appeared on pages 271 to 274 of the July 1843 issue of “The Christian Family Magazine, or Parents’ and Children’s Annual,” Volume 2, no. 6. Both magazines were based in New York (132 Nassau Street) and were founded by the Reverend D. Newell. In addition to those listed, Henry M. Parsons contributed many more articles and poems to these and other magazines. I reproduced the two articles above, starting chronologically with the one on Pico.