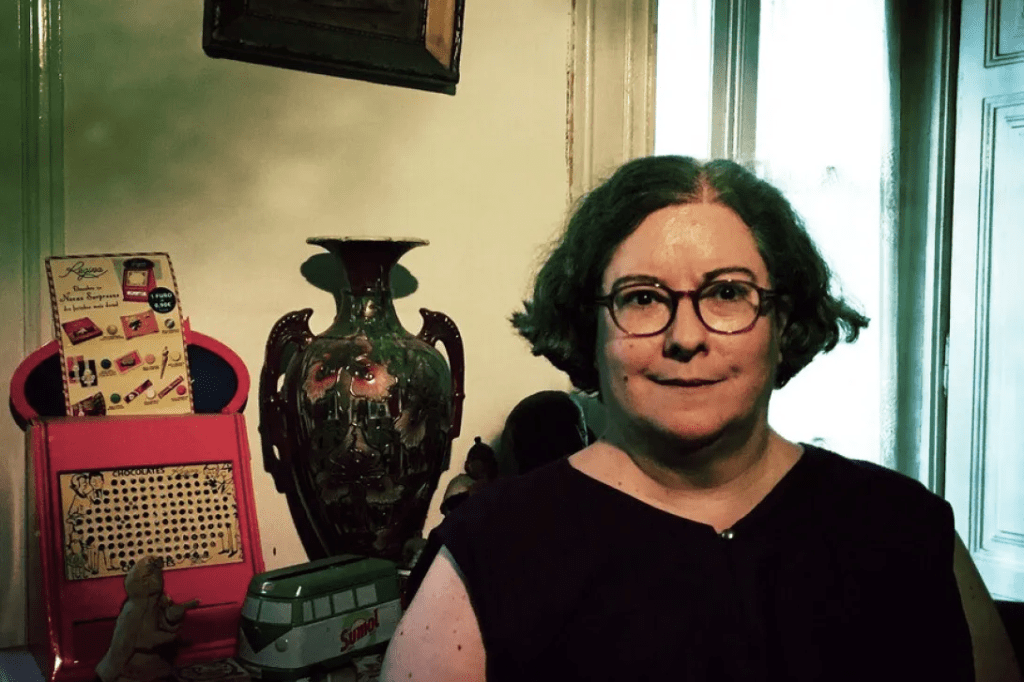

Adília Lopes is the literary pseudonym of poet, chronicler, translator, and documentalist Maria José da Silva Viana Fidalgo de Oliveira, born in Lisbon on April 20, 1960, according to a biography published by the Portuguese Authors Documentation Center of the Directorate-General for Books, Archives and Libraries (DGLAB).

“Adília came about with a poem I wrote in my diary when a cat of mine, Faruk, disappeared,” she said in an interview with journalist Carlos Vaz Marques, quoted on the DGLAB website.

Her journey began as a physics student at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon, a course she left behind after being diagnosed with “schizo-affective psychosis, an illness she always spoke about openly, whether in her poetry, chronicles, conferences or interviews,” reads the biography published by the Portuguese Authors Documentation Center (CDAP).

In the early 1980s, she switched to a Portuguese and French Literature and Linguistics course at the Faculty of Letters. She sent his first poems to the publishing house Assírio & Alvim, which selected two for the 1984 “Yearbook of Poetry by Unpublished Authors.” Shortly afterwards, he released his first book in an author’s edition, “Um jogo bastante perigoso” (1985), a work in which he begins by evoking Esther Greenwood, the narrator of “Câmpanula de Vidro”, a reflection on the deep depression of the American Sylvia Plath.

In the following years, Adília Lopes published “O Poeta de Pondichéry” (1986), one of her most translated works, based on a character from Diderot’s “Jacques, the Fatalist,” which was followed by “O decote da dama de espadas” (1988), a collection of poems from 1983 to 1987.

After graduating, she was awarded a scholarship from the National Institute for Scientific Research (1989-1992) and worked at the Linguistics Center of the University of Lisbon. This was followed by a specialization in Documentary Sciences, where she worked on the collections of Fernando Pessoa, Vitorino Nemésio, and José Blanc de Portugal deposited in the National Library.

From 1987-1991, she is only known for the author’s edition, for free distribution, of “Os cinco livros de versos salvaram o tio,” a kind of paraphrase of the title of Enid Blyton’s adventure book, “Os cinco salvaram o tio.”

And it was exactly the next five books by Adília Lopes, published by small but decisive publishers such as &etc and Black Sun, that brought her her first media success: “Maria Cristina Martins” (1992), “Peixe na água” (with a drawing by Sofia Areal, 1994), “A continuação do fim do mundo” (1995), “A bela acordada” (1997) and “Clube da poetisa morta” (1997).

In 1999, she obtained a literary creation grant from the former Portuguese Book and Library Institute, enabling her to work for the theater and tidy up scattered and unpublished works. The director, Lúcia Sigalho, would then stage “A birra da viva”, based on texts by the writer, a play that would become the core of the “A caixa em Tóquio” trilogy. The organization of her unpublished work would also give rise to “Seven Rivers Between Fields.”

In 2000, he brought together his literary output for the first time in a single volume, “Obra”, with illustrations by Paula Rego (1935-2022) and the unpublished “O regresso de Chamilly”, published by Mariposa Azual, confirming his place in Portuguese literature.

The painter of “Angel” identified an “impressive parallel” between her imagination and Adília Lopes’ poems: “They immediately reminded me of my youth, with the maids, the dolls, the ultra-protective mothers,” said Paula Rego, quoted in the CDAP biography. “Adília Lopes has a great romanticism and at the same time an overflowing grotesqueness and comicality.”

The understanding between the two led Adília Lopes to translate the Portuguese edition of “Nursery Rhymes”, an album of prints by Paula Rego, based on English nursery rhymes.

Throughout the first decade of the new millennium, the poet’s oeuvre expanded with a privileged edition of &etc: “A mulher a dias”, “César a César”, “Poemas novos”, “Le vitrail la nuit”, “Caderno”.

In 2009, she brought her books back together in a single volume, this time “Dobra”, a project that took her back to where she started, to the publishing house Assírio & Alvim, to which she remained attached until the end.

These last 15 years include titles such as “Apanhar ar,” with drawings by the author, “Café e caracol,” “Andar a pé,” “Manhã,” Capilé,” ‘Bandolim,’ ‘Estar em casa,’ ‘Dias e Dias,’ to which were added three more editions of her collected poetry, ‘Dobra,’ in 2014, in 2021 and the final one this year, when she completed 40 years of literary life.

Adília Lopes’ influences include Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen, Nuno Bragança, Ruy Belo, and Roland Barthes, without leaving out Emily Brönte, Countess of Ségur, and Enid Blyton.

“Adília Lopes’ style, apparently colloquial and ‘naïf’, is full of phonetic games, free associations, nursery rhymes and foreign languages,” reads CDAP’s biography. “The themes of everyday life, mainly feminine and domestic, are treated with humor and self-irony, candor and rawness, intelligence and intentionality.”

Her work has been translated into German, Spanish, French, English, Italian, and Dutch, among other languages, and is represented in several Portuguese and foreign anthologies. It has also been studied by academics such as Elfriede Engelmayer, Osvaldo M. Silvestre, Américo Lindeza Diogo, and Manuel Sumares. In March last year, the National Library of Portugal hosted the international colloquium “Going to school with Adília”. The National Ballet Company paid tribute to her in its 2016 program.

“There is always a great deal of violence, pain, seriousness and holiness in what I write,” said Adília Lopes. “Writing poems is good,” but ‘listening to the Muse is exhausting, a frenzy,’ she said at the end of ‘Dias e dias.’

I don’t like books

I don’t like books

as much

as Mallarmé seems

to have liked them

I’m not a book

and when people say

I really like your books

I wish I could say

like the poet Cesariny

listen

what I’d really like

is for you to like me

books aren’t made

of flesh and blood

and when I feel

like crying

it doesn’t help

to open a book

I need a hug

but thank God

the world isn’t a book

and chance doesn’t exist

still and all I really like

books

and believe in the Resurrection

of books

and believe that in Heaven

there are libraries

and reading and writing

© Translation: 2005, Richard Zenith

Childhood Memories

We loved raspberry compote

and we were given a dish with more raspberry compote

than usual

but

our maid and our great-aunt

for our own good

because we were sick

had laced the raspberry compote

with spoonfuls of medicine

that tasted bad

the raspberry compote didn’t taste the same

and it had white streaks

this happened to us once and that was enough

we never again jumped up and down when there was

raspberry compote for dessert

we never again jumped up and down for anything

we can’t say

how yucky the medicine from our childhood tasted!

how yummy the raspberry compote from our childhood was!

when we found out about the mixture

of raspberry compote with the medicine

we fell silent

later we heard about entropy

we learned that it’s not easy to separate

raspberry compote from medicine once they’re mixed together

that’s how it is in books

that’s how it is in childhood

and books are like childhood

which is like Catrina’s little doves

one is mine

another is yours

yet another is someone else’s

ELISABETH DOESN’T WORK HERE ANYMORE

(with a few things from Anne Sexton)

I’ve already walked from breakfast to madness

I’ve already gotten sick on studying morse code

and drinking coffee with milk

I can’t do without Elisabeth

why did you fire her madam doctor?

what harm was Elisabeth doing me?

I only like Elisabeth

to wash my hair

I can’t stand to have you touch my hair doctor

I only come here doctor

for Elisabeth to wash my hair

only she knows the colors and scents and thickness

I like in shampoos

only she knows how I like the water almost cold

running down the back of my head

I can’t do without Elisabeth

don’t try to tell me that time heals all wounds

I was counting on her for the rest of my life

Elisabeth was the princess of all the foxes

I needed her hands in my hair

ah if only there were knives for cutting your

throat madam doctor I’m not coming back

to your antiseptic tunnel

once I was beautiful now I’m myself

I don’t want to be a ranter and alone

again in the tunnel what did you do to Elisabeth?

Elisabeth was the princess of all the foxes

why did you take Elisabeth away from me?

Elisabeth doesn’t work here anymore

is that all you have to say to me doctor

with a sentence like that in my head

I don’t want to go back to my life