It was in the 1990s. In Pilar da Bretanha (Sào Miguel, Azores), I searched for the ancient tradition of celebrating Christmas.

At a daycare center, I met a widowed woman, the mother of a large family, who told me how she prepared her house for the festivities. The first floor was covered with cryptomeria and pine tree greenery, and the whole house was swept like the ground. As poverty was a custom from which only emigration to Brazil freed many families, those who stayed only distributed sweets to the children. The oldest rooster was killed for the dinner party, and the feast of the Child was celebrated with it.

There was little difference from the rural environment that the Englishman Joseph Bullar found when he visited São Miguel between December 6, 1838 and April 14, 1839. Here is his account of how Christmas was lived back then: “In the houses of the poor, the rooms are adorned with boughs of greenery, and in some of them the floor is strewn with branches. In the afternoon, in most huts, the women, girls, and children sit on the floor, cross-legged, with their glossy black hair neatly combed, shiny with oil and sometimes tied up with tall tortoiseshell combs. Others sit in the sun on the doorstep”.

Bullard, describing the house of the French villager Tomasia, confirms the interior decorations: “The floor was strewn with vegetables and the walls and ceiling were covered with green beech branches”. (pg.53).

Also interesting is the description of the social atmosphere in the village on Christmas Day: “Everyone – men, women and children – wears good, tidy, even flashy clothes; no one works and you don’t see donkeys in the streets and even the pigs have taken on an indolent, holy-day air” (…) ‘In the streets, the men wandered about, chatting or gesticulating vigorously in groups at the doors of the taverns, while the kids played nearby in packs’.

After so many years, evolution has reached the world’s furthest corners, imposing new ways of celebrating the Nativity without forgetting old traditions such as the Nativity scene.

Created by St. Francis of Assisi, it has a Catholic tradition. According to Armando Cortes Rodrigues, this tradition “is opposed to the Protestant tradition of Christmas trees in northern countries, due to the impossibility of the images and the fact that it is better suited to the vast snowy expanses of the long months of the year.”

In one of the chronicles published in this newspaper, entitled “For Christmas Eve,” Cortes-Rodrigues, a distinguished poet from the Orfeu group, writes:

“This is a night of stars, not darkness (…) This is the night when the heart burns to embrace the living and the dead. Everyone is at our side (…) We are all together because tenderness is like the light that awakens and revives the things hidden in the dark and because all of this is lived in concentration and silence, in front of the crib that I have put together with my own hands, like a poem that you can read in the future.” (pgs.55-56).

The Nativity scene is, in fact, the most beautiful expression of the artistic staging of the biblical episode of the incarnation of the Savior.

In a book published in 2008, entitled “Nativity Scenes on the island of São Miguel”, the author José de Almeida Mello states:

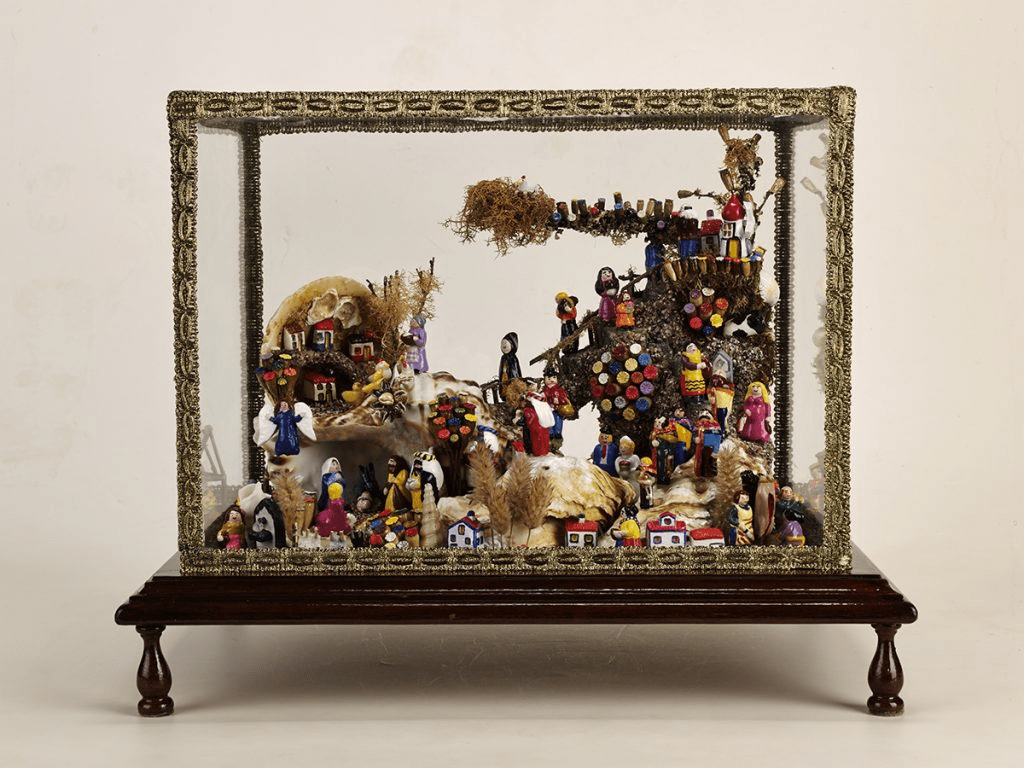

“When we go around the villages, parishes and towns at Christmas time, we will find, not only in churches and hermitages, but also in private homes and some public buildings, a large number of nativity scenes, varying in form: some richer, others poorer; sometimes small, sometimes large; sometimes set up on top of boxes, or on the floor of the house; some even occupying large areas such as entire rooms, where creativity and imagination often predominate.”

Mello states, “The city of Ribeira Grande is the capital of nativity scenes on the island of São Miguel.” You’ll find the Nativity scene created by Father Evaristo Gouveia and the Mystical Arcana there.

On the other hand, the old town of Lagoa is “the birthplace of thousands of figures, known as the Lagoa dolls.” It is also where “the only existing Nativity Scene Museum in the Azores and in Portugal.” (Mello, 2008:10)

There are many other nativity scenes in churches and outdoors, which are very popular. As Mello says, “cribs are a symbiosis of the society in which they are produced”, so some of them, in addition to the biblical scenes of the nativity, are part of the daily life of the population: religious festivities, processions of Santo Cristo and the oragos, pilgrimages, social events, pig slaughter, revelry and celebrations of the Holy Spirit, philharmonic parades, performances by folk groups, costume parades, and other ancient traditions.

The recent restoration of the Lapinha Nativity Scene, built with miniature shells, flowers, and other props, was also worth mentioning. The new craftsmen have introduced new materials, showing a high ecological sense and a signature aesthetic quality. All this means that the Lapinha nativity scene retains the religious meaning of the nativity and is an important expression of popular culture and piety.

Given the great diversity of Christmas expressions, it’s time to make the most of them by incorporating them into the cultural itineraries of São Miguel, as they cannot be hidden from the public in general and visitors in particular.

Revealing old and new artistic productions about the season we celebrate helps us understand our identity and idiosyncrasy.

In Diário dos Acores, Osvaldo Cabral-director

José Gabriel Ávila is a retired journalist with a brilliant career in the Azores.