ACCULTURATION IN ONÉSIMO’S L(USA)LAND

We now conclude the exercise begun in the previous chronicle of revisiting and summarizing Onésimo Teotónio Almeida’s remarkable essay entitled “Portuguese Communities in the United States: Identity, Assimilation, Acculturation,” which will also apply to the reality of Canada.

First of all, it is important to remember the author’s justification for an emblematic term he coined – L(USA)lândia: “At the beginning of my Portuguese-American experience, in the 1970s, I was very impressed by the self-segregation of the Portuguese community, caused above all by the fact that a large majority of emigrants were from a very recent wave and were unfamiliar with both the language and the culture of the host country.”

“The term “L(USA)land” thus came to me in an islander cultural context.” “L(USA)landia was therefore this Portuguese island, surrounded on all sides by America.” “Populated in particular by Azoreans, it was – and still largely is – the tenth island of the Azores archipelago, as well as the westernmost.”

It is in this context that Onésimo addresses the issue of acculturation.

“The defense of the need to assume and preserve the past does not imply that the emigrant should not broaden his horizons and integrate as much as possible into the society to which he emigrates.”

“A middle ground has been sought between the legitimate defense and preservation of their roots, of the culture they take with them, and insertion into the American environment which gives them more opportunities of various kinds and will allow them to develop better overall.”

For Onésimo Almeida, “there is no metaphysical reason for a person to become Portuguese, nor is there any transcendent need for them to become American. Rather, there are psychological laws that condition the emigrant from one culture and the immigrant from another to create mechanisms for survival and balance between these two worlds.”

Ultimately, he concludes, “the emigrant doesn’t emigrate. They simply expand borders.”

One last foray into this essay by Onésimo Teotónio de Almeida is now on the process of acculturation associated with the language barrier.

This immense challenge corresponds to three variables.

“The first observation is that, for the most part, emigrants do not learn the language of the country they are emigrating to very well.”

“Of course, there are differences of degree, since those who enroll in classes specifically for this purpose learn it better, as well as those who live in areas where there are few Portuguese and therefore find themselves needing to speak with communicators of another language. In many cases, this need is limited to working hours, but it is a considerable factor.”

“Another variable that affects the level of acquisition of the new language is the person’s previous level of education. Naturally, the better educated you are, the easier it will be to learn, although this only reduces the effects of the other factors.”

“A third conditioning factor for learning a second language in a foreign country is age. The younger a person emigrates, the easier it is to learn the language. The later you emigrate, the less you lose in terms of knowledge of your first language.”

“This means that the later you emigrate, the more you carry with you the world you used to live in.”

“That’s why emigrants try to reproduce in their new world whatever they can’t carry with them in their luggage.”

“If they go to a world where everything starts all over again, they recreate the social institutions of the country they left behind.”

Daniel de Sá summed up this great dilemma of Azorean emigration: “Leaving the island is the worst way to stay on it…”

And Onésimo Teotónio Almeida concludes his essay in this way:

“In the long run, acculturation and assimilation by the American mainstream will be inevitable, but this will happen more easily in small communities or among the Portuguese who have dispersed throughout the country.”

“The communities concentrated in Southeastern New England are likely to endure for a long time, even beyond the survival of the Portuguese language as a common vehicle of communication, as is still the case with emigrants, including naturalized ones.”

“The inevitable disappearance of Portuguese as a first language in the generations already born in the United States will not in itself cause the cultural marks of the communities to disappear.”

“Portuguese will continue to be taught as a second language in schools and universities, and it is only natural that it will be reinforced, especially in higher education.”

Despite everything, this is a good conclusion.

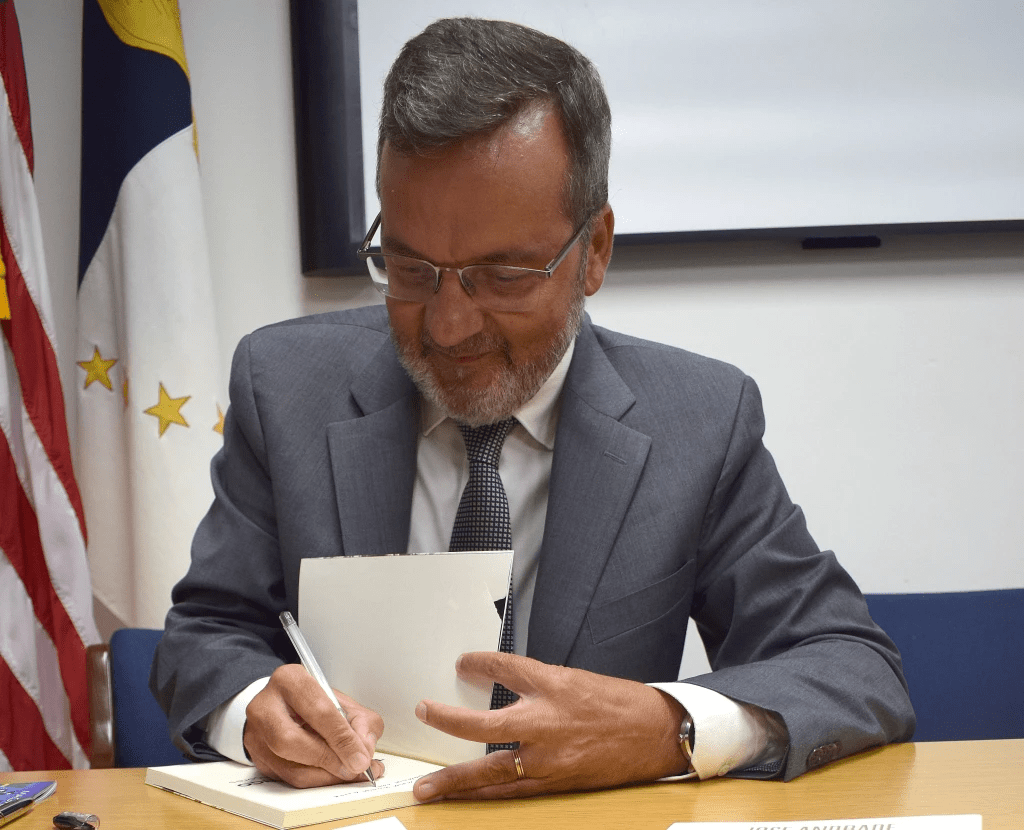

It is also a hymn of praise to our honoree, a university professor and cultivator of the Portuguese language on the other side of the Atlantic.

_____

José Andrade is the Regional Director for Communities of the Government of the Autonomous Region of the Azores

This piece comes from his book Transatlântico – As Migrações nos Açores (2023)

Translated by Diniz Borges

Translated to English as a community outreach program from the Portuguese Beyond Borders Institute (PBBI) and the Modern and Classical Languages and Literatures Department (MCLL) as part of Bruma Publication and ADMA (Azores-Diaspora Media Alliance) at California State University, Fresno, PBBI thanks the Luso-American Education Foundation for sponsoring FILAMENTOS.